Climate change may be shifting turtle sex ratios. But you’ve got to go the distance to prove it. Natalie dos Santos on the hard yards and sweet pleasures of research in a little piece of paradise.

First published by Daily Maverick

Watching a turtle dig her nest is always my favourite part of the evening. I sneak up behind one, nestle into the sand to get comfortable, and then watch mesmerized as the prehistoric animal prepares to lay her eggs.

There is just enough starlight to make out the wet parts of her carapace. After three methodical scrapes along the bottom of the nest, she slowly lifts a flipper with a perfect cupful of sand and places it beside her. A moment later, with a swift movement of her other flipper, she flicks sand into the air before lowering the flipper carefully back into the nest to repeat the process.

On some nights when the weather or other conditions were wrong we would not see a single turtle. When that happened, the 10km walk from the research station to Beacon Twelve-North (12N) and back seemed never-ending. Beacon 12N is the farthest point on a 5 kilometre stretch of the KwaZulu-Natal coastline.

The beach, a narrow stretch between the Kosi Bay system and the Indian Ocean, is known as Bhanga Nek. Among turtle watchers it’s regarded as a high-density nesting site for loggerhead turtles (Caretta caretta). In my eyes, it’s an absolute paradise.

I was among a group, volunteers and marine biology students from Nelson Mandela University, who spent the better part of four months walking its length. Usually this was in the dark, as we searched for nesting loggerhead and leatherback (Dermochelys coriacea) turtles. Later our attention turned to hatchlings.

After a few nights on these foot-patrols, our eyes needed only seconds to adjust to the pitch-black beach. We learnt to recognise where we were by the outline of the dunes and trees.

We passed local tour guides sharing their knowledge of the area and its turtles with small groups of tourists. We never saw their faces in the dark, but soon became friends with two of the guides, Agrippa and Simanga, recognised only by their distinct voices. Their passion for turtle conservation was unquestionable and we looked forward to spotting their familiar silhouettes.

Also on the beach were local turtle monitors, involved in the Ezemvelo KZN Wildlife turtle monitoring programme, which has been running successfully since the 1960s.

Playing tag

Our group arrived in the middle of the turtle laying season, which spans October to December, and jumped straight into general monitoring. This involved tagging turtles with numbered titanium markers, recording existing tag numbers and taking carapace measurements.

We also assisted other researchers with their fieldwork, including collecting DNA samples and epibionts – tiny organisms that live on the surface of animals including turtles. Counting and measuring eggs was another part of the work.

When it was time to watch a nesting turtle, one of us would stay awake while she dug, waking the rest of the team as soon as laying started. As the first egg dropped, the turtle entered a trance-like state. This was the best time to work without disturbing the turtle.

Climate change

My research involves measuring nest temperatures and predicting the sex ratios of turtle hatchlings. A turtle’s sex at birth is determined by its nest temperature, making the ratio of males to females a useful indicator of changes in climate. In general, warmer temperatures produce females and cooler temperatures produce males.

By comparing loggerhead nest temperatures to a similar study done in the 1980s, I’m hoping to see whether climate change may be affecting the South African turtle population.

Taking the temperature

The idea seems simple, but measuring nest temperatures can be fiddly.

I inserted temperature probes, known as iButtons, into loggerhead nests on nightly patrols. These thumbnail-sized devices are calibrated to record temperature every 30 minutes for the entire incubation period of roughly 60 days. The goal was to retrieve these once the nest hatched.

The probes were enclosed in a ping-pong ball to protect them from corrosion and make it easier to get them out the nest later. They had to be deposited amidst the egg mass as the turtle was laying.

I set up a few evenly spaced control iButtons in the sand elsewhere on the 5km beach. This would let me see the difference between the sand and turtle nest temperatures. We marked the location of all the iButtons with a GPS, as well as with a fishing line tied to the nearest vegetation.

The physical markers had to be inconspicuous so as not to attract attention and reveal the nest location to poachers, but also not so inconspicuous that they were impossible to find nearly two months later… more about that in a bit.

Sleep walk

The turtle monitoring area is marked with beacons spaced roughly 400 metres apart. This makes it easier to allocate smaller monitoring zones.

From our starting point at Beacon Zero-North (0N), the walk to 12N was difficult at first. I would often sleep-walk the last beacon home while Christopher Nolte and Bruce Roestof, the PhD and MSc students who accompanied me for much of my first field trip, strolled effortlessly beside me.

One night, Bruce made a very good point (at least, I thought so at the time): “Natalie’s legs are half the length of ours, so technically she is walking twice the distance we are!”

Some nights we would come across up to 10 loggerheads and, if we were lucky, a few leatherbacks. We would take turns keeping watch as we waited for them to lay. Choosing a spot and digging a nest was never a rush job for a turtle. It was a good time for us to steal a nap under the stars.

A Team

After a few days, Chris, Bruce and I fell into an easy working rhythm and knew exactly what to do when we came across a loggerhead or leatherback.

Chris has been researching turtles at Bhanga Nek for a few years and had a lot of knowledge to share. He’s a great teacher and, I soon learnt, a gentle giant too, along with the fact that he hates onions, coffee and a variety of other food besides bread, tomato sauce and meat.

Bruce, an entomologist, had come to Bhanga Nek as a volunteer. He was a crazy fisherman, as wild as the hair on his head. When he wasn’t working with turtles at night, Bruce could be seen through a pair of binoculars, a tiny speck on the shoreline far away, fishing rod in hand. He would finish his morning chores by 8am, then pack a peanut butter sandwich and go fishing all day long. The three-spoon coffee he made to stay awake for nightly patrols became affectionately known as “The Bruce”.

The other volunteers that joined us over the next few weeks were all truly great, but I still like to think that Chris, Bruce and I were “The A team”.

Turtle Shack

After patrolling into the early hours on most nights, we would get a few hours of sleep in an epic little research station, known as the Turtle Shack, before being forced out of bed and into the ocean by an unbearably hot sun at 6am.

The Turtle Shack has been standing for almost as long as the turtle monitoring programme itself and has as much character as Bhanga Nek and its old, wise nesting turtles. Much of its walls are made of reeds from the nearby Kosi Lake system. Every hinge is rusted, every window covered in sea salt and it is home to resident mouse, Dolores, who has more of an affinity for plastic goods than food items. It felt like home instantly.

During nesting season we spent most days doing a few chores, reading scientific papers and exploring the shallow reefs in front of the shack. Being the first one in the water upped your chances of finding resident green turtles at their cleaning stations. Often I also came across beautiful spotted eagle rays soaring through the water. When the wind turned the sea upside-down, we went snorkelling in Kosi third lake and once in the estuary mouth among huge eels and stonefish.

In the afternoons, we read books on the shady porch and took much-needed naps. We also spent time chatting to rangers from the local community, learning about their lives and culture. By the time I left, Mabuusi KaMgabadeli Ndlazo, Ntombifuthi Anele and Zandile Sizakele Kunene had become my good friends and each of them, ‘sisi wami’ (my sisters).

It was hard saying goodbye to these beautiful people, but each time I went back I was warmly welcomed, loud enough for all of Bhanga Nek to hear, along with the biggest hugs, laughter and once, a dramatic collapse onto the beach sand by Busi.

Day nesters

On some afternoons, sitting on the porch outside with a pair of binoculars, we were lucky enough to spot turtles coming up the beach to nest. These rare day-nester visits never failed to excite.

We would throw on our green reflective vests, grab the backpacks filled with measuring equipment and run to witness the sight along with the rangers. Locals and tourists – some of whom had never heard of a turtle – would gather nearby and ask questions. “Is there anything else that walks out of the sea around here?” asked one woman anxiously.

Back for hatching

The fieldwork in the hatching season, in January, was far more difficult.

Along with the nightly foot patrols, looking for adults still laying eggs and hatchlings running down the beach, there was a 5am shift taken on by Ronel Nel – a marine scientist based at Nelson Mandela University – and her husband, Lorenz, looking for nests that were about to hatch.

Being an early riser, I joined these shifts while the other students slept. It was a chance to absorb as much knowledge as I could from Ronel, an expert on South African sea turtles.

Returning to the research station with the hatchlings we had collected, I took great pleasure in waking the other students by banging pots and calling them to work: “Hatchliiiings!” All of us would then set to work, coffee-making, hatchling distribution, measuring, weighing, DNA-collecting and scribing.

Later, we either returned the hatchlings to their nest or had the privilege of releasing them. It was quite a sight as a bunch of students in their pyjamas ran around chasing predator ghost crabs away, taking photos and making sure each hatchling made it safely to the ocean.

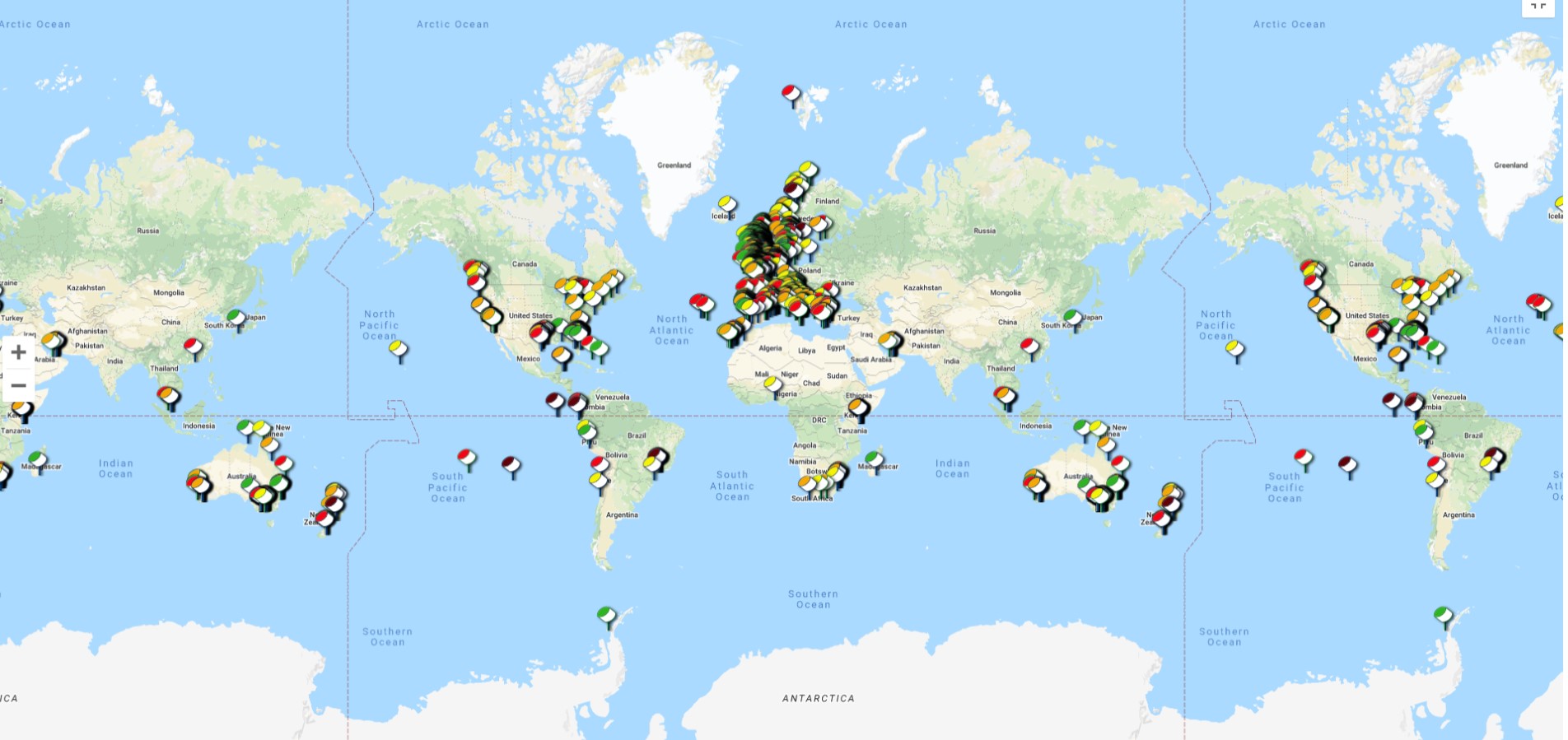

The hatchlings then begin their “lost years”. Researchers aren’t too sure where they go until they return to their feeding habitats around the world as juveniles.

Needles in a haystack

After the fun of the early morning, came the hardest part of the day.

We broke into teams, each armed with a GPS and spade, and set off in search of the iButton temperature probes I had put into the turtle nests two months earlier.

It was a cause for celebration when we retrieved one, but we soon discovered our GPS coordinates were off the mark by up to 30 metres in some cases. To make matters worse, our physical markers were frequently missing or buried in mounds of sand.

I soon realised these iButtons were needles in a haystack… a 5 km-long sandy haystack… that shifts every time the wind blows and the tides change.

Even the control iButtons proved hard to find and of the ones we did retrieve, a few were unfortunately faulty. A mountain of valuable temperature data was lost, but we stayed positive, devising plans to salvage our search.

Bird head brings metal detector

A good friend of mine, Andy Coetzee, better known in these parts as “Khanda Linyoni” for the feathery fly-fishing ties stuck into his cap, came to help with my iButton hunt and to get an update on research being done in Bhanga Nek.

Andy worked with turtles and lived at Rocktail Bay and Mabibi for many years. He is without a doubt, a Maputaland local.

He is even crazier about diving than me and I couldn’t wait for his arrival, not only to have a freediving buddy, but because he had organised a metal detector to help with the iButton search.

Long story short, the metal detector plan failed and it was back to what he called “mining Bhanga”. We continued to dig in the general area of the nests, hoping for a miracle, with only one actually happening. Our other strategy was to wait for the hatchlings to emerge and hope to follow their tracks back to the nest and iButton before wind or tide washed them away. One more iButton was retrieved this way, bringing our count up to half of all the iButtons deposited into loggerhead nests.

Lessons were learnt, “school fees” paid. I took many notes on what could be improved to make retrieving iButtons easier for future studies. And it was great having Andy around to learn from, help with digging and taking photographs and to freedive with.

Determined

After a few days of 5am shifts, digging up the beach at the hottest time of day, diving in any gap I could find and leading a team of students on late-night foot patrols, the lack of sleep started to catch up with me.

One night, we got back to the Shack around midnight, exhausted, only to learn a nest of leatherbacks needed to be measured, weighed and sampled for DNA.

We finished with the leatherback hatchlings in the early hours. I could have fallen asleep on the spot, knowing I had to be up soon. But it was magical looking up at the starry sky, with the Milky Way illuminating the beach just enough to watch the little leatherbacks crawl towards the ocean with absolute dogged determination.

Much later that morning I myself crawled, sleepily into my bed, and thought, I wouldn’t have it any other way.

Start of something

Most of my fieldwork at Bhanga Nek came to a close at the end of January as university lectures started.

While I look forward to getting stuck into data analysis and writing, I keep thinking back to my time at this special place. Bhanga Nek, its nesting turtles, its people and its beautiful shallow reefs stole my heart.

I was sad to leave, but grateful I had been there and for the opportunity to do research with the help of WildOceans and my supervisors, Professors Ursula Scharler and Ronel Nel, and to be involved a little in the conservation of these remarkable animals.

I hope this is the start of something big and meaningful for my career as a marine scientist… and I hope to see the hatchlings I watched crawl into the ocean come up the beach in 30 years’ time.

- Natalie dos Santos is working on an Honours degree in Marine Biology through the University of KwaZulu-Natal. She is enrolled on Roving Reporters environmental journalism training programme, Developing Environmental Watchdogs and the WildOceans Ocean Stewards programme which gives young scientists the opportunity to explore offshore marine research.

How the Daily Maverick covered the story

Now read

Dangling limpets and silver dancing girls provide food for thought

Marine biology student Natalie dos Santos learns how many amaMpondo live off the sea and wonders if there might be limits to the feast it provides.