Marine biology student Natalie dos Santos learns how many amaMpondo live off the sea and wonders if there might be limits to the feast it provides.

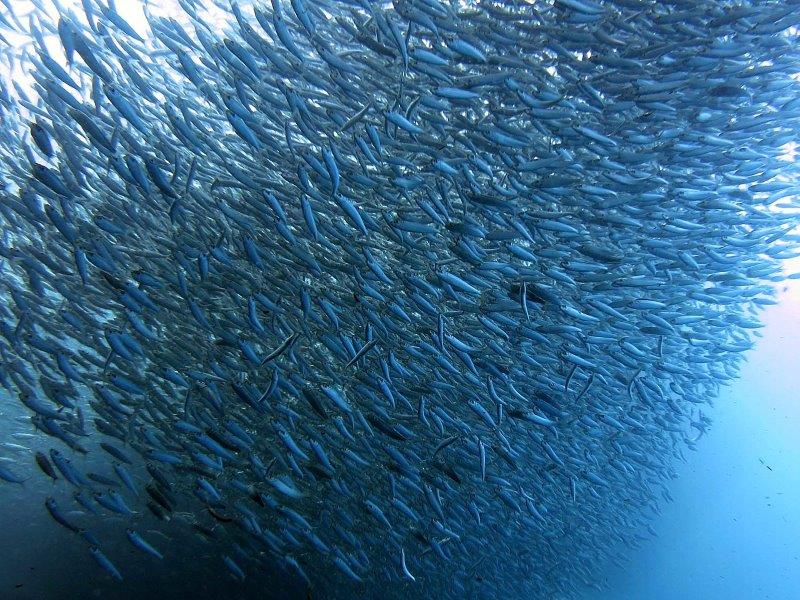

Late July is a special time on the Wild Coast. The sea comes alive with shoals of sardines and pods of dolphins, diving cormorants and humpback whales. The crisp early morning sea breeze wakes the tired eyes of AmaMpondo locals as they head to the beach with fishing rods, buckets, hammers and chisels.

It’s also when the blue shad arrive. “They are bigger than the normal shad,” says Lonwabo Dlamini, referring to the shad, or elf (Pomatomus saltatrix), that make their way from the cold waters of the Cape to KwaZulu-Natal to spawn.

‘Saltatrix’ means ‘dancing girl’ – a species name derived from the way it fights on the end of a line. The ‘blue’ shad that Lonwabo eagerly speaks of are the larger adults, whose juvenile silver-green bodies develop a blue sheen as they grow older, reaching one to two kilograms.

Saltatrix

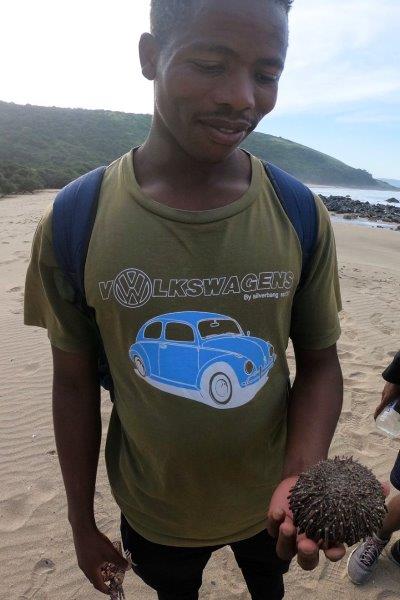

Lonwabo seems shy, but his gentle nature and soft smile draw me in. He displays a puzzled, intrigued expression on his face when listening to others. Get him talking about fishing, and the creases on his brow relax, his eyes light up and he reels off countless names of fish and shellfish.

Lonwabo Dlamini inspects a sea urchin. Photo: Natalie dos Santos

When I asked Lonwabo how he knows the names of all these fish, he chuckled. He didn’t learn about them from books like I did, but from his father and older sister. At the age of five, before he knew their names, he was taught by his father how to catch them.

Pointing to a rocky pinnacle with waves crashing onto its face below us, he showed me a good place for blue shad. It is better to cast off the side, so your line does not get cut on the sharp rocks, he says.

Sharp

As a young boy, Lonwabo would set off in the dark for the beach. He would make the long walk with his father and sister from their village, Sigidi. By the time Lonwabo had his first catch of the day, the sun would be warming his forehead. He tells me he catches rock salmon, rock cod, bronze bream, blacktails and kingfish.

I ask if he catches mackerel or snoek. The names don’t register so I get out my cellphone to show him a photo of one. No, he laughs, those are the deep-sea fish, you can only catch them from a boat.

Lonwabo has never needed a boat to help feed his family. He was a seasoned angler by the time he was 10 and had also learned to catch crayfish – a riskier business amid crashing waves on the Wild Coast’s rocky shores.

Long hike

Now, at 27, Lonwabo is learning to be a hiking guide. He has been taken under the wing of Sinegugu Zukulu, a veteran guide and former geography teacher.

Lonwabo joined us on a five-day, 74 km hike from Ndengane village to Port St. Johns, led by Sinegugu.

I had been invited along by environmental journalism training agency, Roving Reporters. Intrigued by stories of shipwrecks and unforgiving seas, I had always wanted to explore the Wild Coast. Here was my chance. It was also an opportunity to learn about environmental journalism, and do something to help conserve this pristine coastline.

Wild hikers at Msikaba village. From left to right: Sinegugu Zukulu (hiking guide), Mlu Mdletshe, Matt Vend, Wilna Moolman, Elsabe During, Adele Pansegrouw, Ma Ntshangase (host), Erna Lubbinge, Audrey Van Eeden, Laureen Statham, Alice Thomson, Natalie dos Santos and Lonwabo Dlamini. Photo by Mzo Madikizela.

Also on the trek were Mlu Mdletshe, a Durban University of Technology journalism graduate, writing mentor, Matt Vend, and seven others – four keen hikers from Pretoria, affectionately named ‘The Tannies’; Laureen Statham and Audrey van Eeden, who hilariously referred to themselves as ‘Law and Order’; and avid environmentalist Alice Thomson.

Homestays

After two days we arrived at the Rhole Village homestay. There was no tapped water or flushing toilets. Just four small buildings, a rondavel and a tiny corrugated iron room where a small fire is used for cooking and to heat water for bathing. The gentle smile of our host, Nogcinile Ntuli, made me feel at home as we were led into the rondavel where mattresses with mismatched colourful blankets and pillows lay on the floor.

Rhole Village home stay host, Nogcinile Ntuli, supplements her income harvesting grass and weaving mats and baskets. Photo: Natalie dos Santos

Over dinner we learned how the ocean provides a living and feeds many here. Lonwabo, who has a subsistence fishing permit, can make R100 from selling a single crayfish. One of Nogcinile’s neighbours had been up the previous night till 1am catching crayfish. When we arrived at the homestay, two men from Durban were there, buying the entire catch.

Tentacles

Halfway through our meal, Nogcinile offered us cooked octopus – ‘ingwane’. Lonwabo took a big serving while describing how he caught them. They look small in their crevices, but when he pulls them out, their whole body emerges and latches onto his arm. I imagined a large mottled brown octopus stuck on Lonwabo’s muscular arm; its tentacles taut like an outstretched elastic band as it struggled to save itself from the pot. I was glad to be eating my plate of fresh veggies from Nogcinile’s garden, not understanding how anyone could enjoy eating this grotesque but incredible animal.

Lonwabo told me he had once watched an octopus suck the meat out of a crayfish in a matter of seconds, leaving only the exoskeleton. He said octopus were scarce now.

Pristine

I felt a sudden weight as I wondered whether these pristine waters, already pillaged by offshore commercial trawlers, were being overfished from the shore too. The laughter and conversation at the table was drowned by the sound of white noise between my ears. It seemed like the locals knew their daily limits and took only what they needed from the sea, but how many crayfish would one struggling woman be willing to catch, especially when men were coming from Durban to buy them? Why come all the way here when it was crayfish season back home? Who was here to regulate the amount being taken?

Daily limits

I asked Lonwabo if people took too many fish or shellfish here. No, they keep within their limits, as do other villagers who come to fish, he said. It would have been heartening to believe all this was true, but something just didn’t sit right. Perhaps it was just my perception, coming from Durban where bag limits were frequently flouted, undersized fish regularly caught, licenses forgotten at home and illegal gill nets strung across rivers at night. This was especially the case after Ezemvelo KZN Wildlife ceased to have a presence on the coastline.

Up hill and down dale. Day three of hike, and 18km to go. Photo: Natalie dos Santos.

We walked on the beach for most of the following day – a good place to learn more about Lonwabo’s life and his relationship with the sea. This stretch of coastline is ingrained in his very being.

As we spoke, a large Mpondo woman walked past with a bucket in one hand and a crowbar rested nonchalantly on her shoulder – an oyster collector. A scraggly dog followed behind excitedly. The woman’s mouth spread into a wide gap-toothed grin as she greeted us.

Gesturing, Londwabo described how he also harvested oysters and mussels, ‘imbaza’, using a hammer and chisel. Lonwabo told me he also catches limpets, ‘isibebe’, which he used as crayfish bait. He chuckled at my baffled look. I had never known a crayfish to be caught with bait. Back home, divers swim out to reefs and stick their hands under ledges to pull out crayfish.

Limpets

We continued along the beach, up steep hillsides onto grassy headlands, following well-used paths. Soon we came across a pile of limpets on the grass. Lonwabo picked up one, holding it close for me to examine. A small hole had been poked through the shell. Lonwabo showed how fishing line or wire was threaded through many limpets and then dangled outside a crayfish’s hiding spot. Once the crayfish started feeding on the limpets, the line would slowly be lifted, bringing the crayfish out to be caught. A clever way to catch them without getting in the water or losing a finger to an eel, I thought. Satisfied with my understanding, we walked on.

Above left: Lonwabo Dlamini stops along the trail to greet Mpondo women harvesting oysters. Right: Lonwabo reveals how small holes are poked through limpet shells for stringing up as crayfish bait. Photo by Natalie dos Santos.

There were one or two fishermen on almost every beach and more on the hillsides carrying long fishing rods tied in bundles over their shoulders. I had not expected the sea to form such a huge part of the amaMpondo’s everyday lives.

Near Mboyti, which means beans, we came upon a poster titled “Line fish on the East Coast”. Lonwabo beamed as he pointed out scratched and faded images of all the fish he had caught, turning to me excitedly when he found his favourite: blue shad.

Too many fishers – too few fish, reads a poster in Mboyti. Photos: Natalie dos Santos.

The next morning, scattered on grassy banks near the beach were remnants of small fires – and piles of mussel shells beside them. Someone had feasted. It brought me back to the topic of overfishing. Were the locals not perhaps harvesting too many mussels? Again, Lonwabo was adamant: they only took what they needed, each keeping within their daily limit of 60 mussels.

The remains of a fire and harvested mussels. Photo Natalie dos Santos.

Later, walking at the very back of the hikers, Lonwabo stopped to pick and eat sweet, sticky red berries known as ‘num nums’. It struck me there was little that could rush him. He had all the makings of a good guide: patience, a willingness to answer questions and share stories, especially those about the sea. His knowledge transcended what one could learn from books and field guides. The sea is, quintessentially, his life.

I left with a real affection for Lonwabo, the AmaMpondo and a coastline I had come to know and love. For centuries, the people of the Wild Coast have lived simply and treaded lightly on her. She has provided in return. I wonder for how much longer, though.

Commercial trawling, mining plans, proposed harbours, out-of-town crayfish buyers, oyster collectors and overfishing – all threaten the pristine nature that sustains a way of life.

Still I’d like to think Lonwabo will catch many big, blue shad for his family this season, and for generations to come.

Guide Lonwabo Dlamini helps Natalie dos Santos with a nagging blister. Photo Adele Pansegrouw.

-

Natalie dos Santos is a final year marine biology student enrolled on the educational Ocean Stewards programme run by WildOceans. Her Wild Coast hike was sponsored by the 8 Mile Club, compliments of the Wild Swim expedition which raised funds for marine conservation and eco-tourism on the Wild Coast.

FEATURED IMAGE

The annual sardine run provides a feast for many. Photo Lakshmi Sawitri