Surfer and sometimes shark researcher Sean Kelly takes a salty look at shark skin, a marvel of evolution.

First published by South Coast Herald

Legs spread almost a metre apart. Each knee presses down on a pectoral fin. Lactic acid builds in my forearms from applying the downward pressure necessary to handle the 3-metre-plus six-gill shark between my legs safely.

Six-gills, or cow sharks as they are often known, have vertebra that does not calcify. It makes them tricky to work with as it allows them to contort to the point they could bite the base of their tail (precaudal pit) or worse, me! But that’s what happens when you handle sharks. The teeth are always a hazard.

What you might not be thinking about is the shark skin eating away at my inner thighs. Ladies and gentlemen, I introduce to you, “shark rash” – a very real and painful eventuality of being a shark researcher.

Exceptional

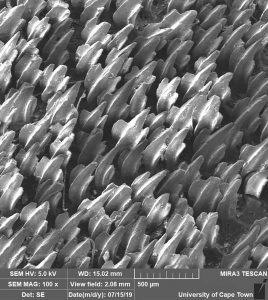

Shark skin, characterised by its grey colour and rough texture, is truly an exceptional piece of evolution. In fact, it is still widely debated among scientists as to what came first: was it a shark’s teeth, or its skin? The two are homologous in their structural makeup.

Shark skin is made of a matrix of tiny, hard structures called dermal denticles or placoid scales. They have the same structure as all teeth with an outer layer of enamel, dentine, and a central pulp cavity. This makes tagging sharks (even the small buggers) a tall ask.

All of the spines of these denticles point backward, towards the tail. Unlike fish scales that grow as the fish does, these denticles never get bigger; they simply become more numerous to accommodate for growth. Such is the sandpaper-like feel of shark skin that in medieval times, knights used it on the handles of their swords; it made for one helluva grip when going into battle.

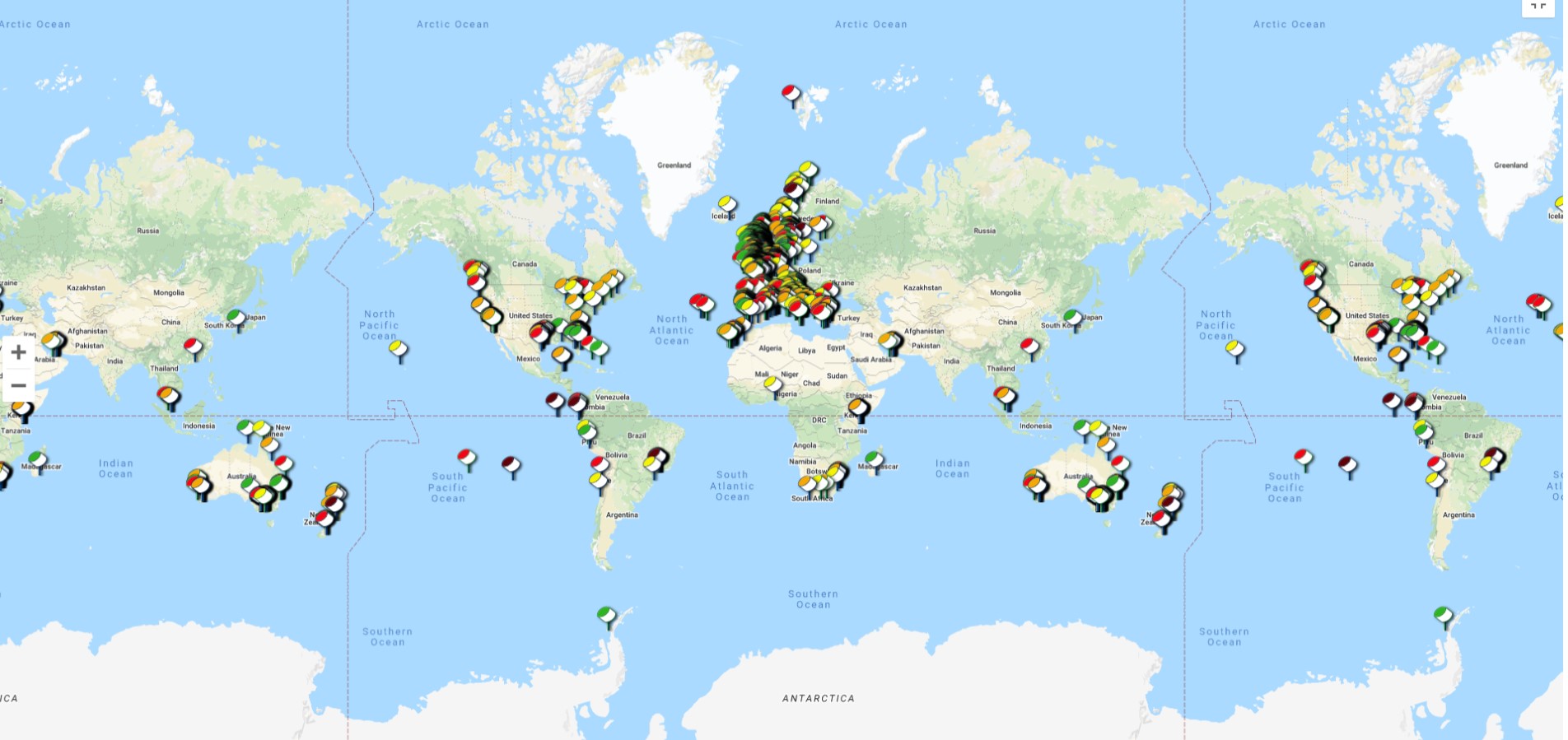

With a history spanning more than 400 million years, sharks can teach us a lot about speed and efficiency in the water. Researchers are trying to make artificial shark skin that would prevent algae and barnacles accumulating on surfaces in the water. There is even hope it might prevent bacteria from growing when used on hospital surfaces, a form of biomimicry.

Bad roastie

But back to shark rash, the bitch of being in the field. It’s the aquatic equivalent of a bad roastie with the addition of urea being applied to the wound. Before you run away with this one, let me reel you in. I’m not saying sharks take the piss when you handle them, but rather that they produce urea. This is excreted through their tissue to prevent them from turning into bokkoms (fish biltong) in the salty seawater.

In 2017 I met a man, Hans, whose livelihood rested on his ability to catch sharks for wealthy tourists so they could get that classic “big fish” photo. While on charter with a bunch of Russian housewives on a getaway from their husbands, who could probably hammer a nail into concrete with their fists, Hans lost more than his patience.

Gangrene

After landing a sizable thresher shark, Hans received a PK from hell across the back of the calf from the thresher’s whip-like tail which it uses to stun its prey. The result, Hans required a skin graft as the urea that contaminated his shark rash went gangrenous.

The point of this column? Well a shark’s a shark. They’re up early, biting things and chasing stuff reminding everyone that they’re a freakin’ shark. So we might as well get to know them, not fear them and perhaps foster a better attitude towards protecting them. – Roving Reporters

• Sean Kelly – @the_sharkman – was one of a number winners in a writing competition on sharks and rays run by Roving Reporters. WildOceans, a programme of the WildTrust, supported the competition and facilitated access to conservation-minded youth, keen to share their passion and develop writing skills. Roving Reporters provided mentorship. Opinions and views expressed in this Ocean Watch series are not necessarily those of the WildTrust.

• Kelly is a freelance copy and feature writer as well as the online editor for Zigzag Surf Magazine, Africa’s foremost surf magazine. He holds an Honours degree in Environmental Management from Stellenbosch University. Before joining Zigzag he worked as the skipper and field coordinator at the South African Shark Conservancy.