Did orcas frighten away False Bay’s cow sharks and what became of the great whites? Marine biologist Leigh de Necker and the Shark Spotters research team, play sleuths

First published in Daily Maverick

We had hardly settled back onto the boat, let alone had the chance to contemplate the killings and what or who may have caused them, when Tammy Engelbrecht sounded the alarm.

“Look!” she cried through a mouthful of peanut-butter sandwich, “A whale.”

Humpback, Bryde’s or southern right whales certainly visit boats, but this was something else.

“Orca!” Dr Alison Kock confirmed.

With most of my dive gear still on, I stumbled to the side, punching my hand into the water with my GoPro, to snap a lucky shot.

The orca, also known as a killer whale (Orcinus orca), glided by, beneath us.

It was not even a minute later when a second orca surfaced a few short meters off the bow of our boat. We had our prime suspects; the chase was on.

This story begins in 2015 when members of the Shark Spotters research team – Kock, Engelbrecht, Dave van Beuningen and myself, Leigh de Necker – started getting reports from recreational divers of dead broadnose sevengill, also known as cow sharks (Notorynchus cepedianus), at Miller’s Point.

There’s an old slipway at the point, located in False Bay on the Cape Peninsula, which makes it an easy place for divers to reach the kelp forest from the shore. Large granite rocks extend above the water. Below, sandy channels separate reefs, with caves and overhangs. Invertebrates brighten nature’s architecture with bursts of colour. Scuba and freedivers soon find themselves deep in a kelp forest wonderland.

It’s a complex habitat, home to many fish and shark species found only in temperate Southern African waters. These include leopard (Poroderma pantherinum) and pyjama (Poroderma africanum) catsharks, spotted-gully sharks (Triakis megalopterus), puffadder (Haploblepharus edwardsii) and dark (Haploblepharus pictus) shysharks.

Broadnose sevengill sharks are named for their blunt nose, broad head and seven gill slits, where most shark species only have five. They are among the most primitive shark species with adults reaching a maximum length of three meters. With a face resembling a dirty oven mitt and behind a deceptive, toothless smile, hide rows of razor-sharp, cusped teeth on the upper jaw. The lower jaw’s teeth are jagged and comb-shaped allowing them to feed on a variety of prey.

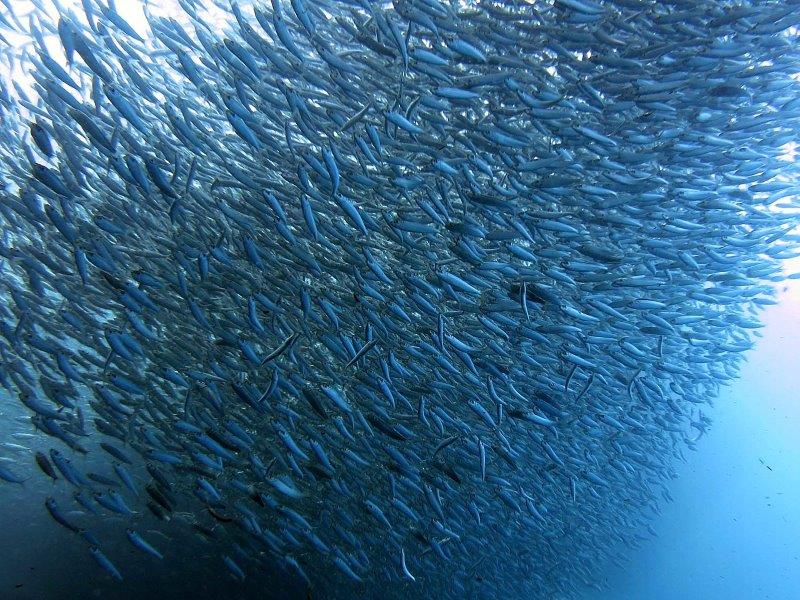

They pass the summer days, researchers suspect, sheltering in the kelp forest. At night they leave to hunt in deeper waters. Between October and January, sevengill sharks saturate Miller’s Point. They cruise its sandy-bottomed highways through the kelp forest, while divers, awkwardly suspended visitors in wetsuits, make way for their prehistoric, armoured hosts.

It’s truly a magical place, showcasing the diversity of sharks found within False Bay. At least that was the case until mid-November 2015 when the grisly discoveries began. Divers started finding scattered sevengill shark carcasses lying among the reefs, in what, contrary to expectation, had become an ominous, underwater graveyard.

Our research team rushed to the site, launching the boat on a perfect early summer morning. Van Beuningen and I kitted up and hopped into the water to search for evidence at the proverbial crime scene.

I have done countless dives at Miller’s Point and been fortunate to spend hours in the water observing these magnificent, docile dinosaurs. Finding an animal I respect and appreciate, dead in it’s underwater home, was heart-breaking.

Divers from Pisces Dive Centre, in Simon’s Town, had collected three carcasses before our investigatory dive, so when we found carcass number four, we knew we had to perform full necropsies.

All the carcasses shared the same external and internal injuries. Most noticeably, a tear from the pectoral fins across the abdomen of the shark, exposing the body cavity, with only the liver removed from an otherwise intact carcass. It looked like a cut, executed precisely, almost as if done with a knife.

Fishermen

At this point, we were thinking fishermen had caught the sharks. Sevengill shark meat has little commercial value so they may have removed the large, oily livers to use as bait.

But Miller’s Point is in a marine protected area, where fishing is prohibited. It seemed unlikely sharks were being slaughtered without the authorities noticing.

Detective divers, Van Beuningen and I were barely back on the boat and yet to digest all this when Engelbrecht spotted the orca and we began the chase. For two exhilarating hours we tracked the pair, who later became known, infamously, as “Port” and “Starboard.” They led us south for six kilometers until we lost sight of them off Smitswinkel Bay.

We moored and went straight to Pisces Dive Centre to do full necropsies on the four carcasses. The killer whales, we discovered, had left behind a key bit of evidence. Stamped on the pectoral fins of each of the carcasses were distinct tooth impressions. Guilty!

Immediately after we first saw Port and Starboard, all surviving sevengills fled. A few months later, sevengills began returning sporadically to Miller’s Point, but so did the shark-specialist hunters. The more we saw the two orcas in False Bay, the less we saw the sharks. Ultimately, the sevengills abandoned Miller’s Point.

On the move

Port and Starboard were on the move too.

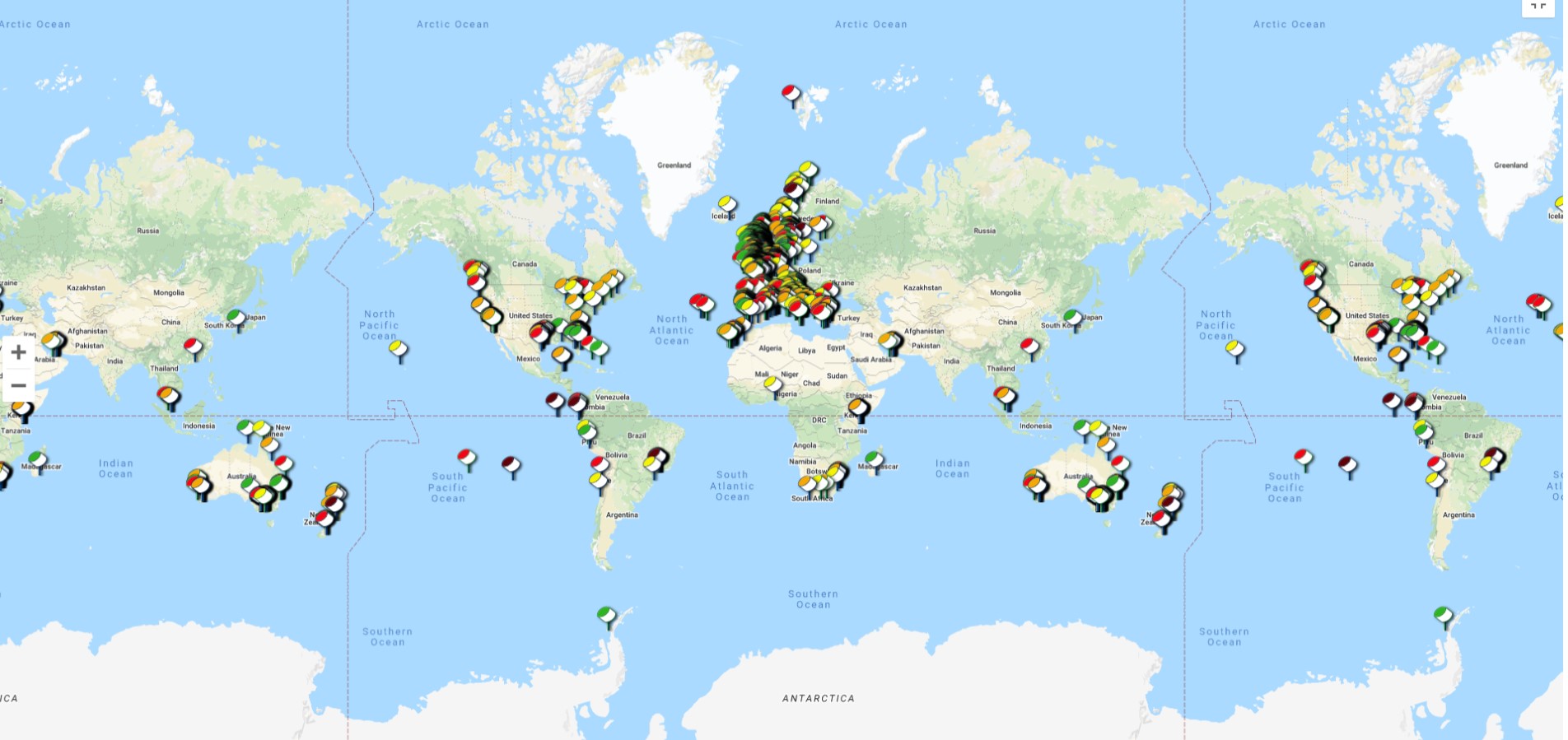

Numerous accounts followed of them being sighted about 200km east of False Bay, at the white shark (Carcharodon carcharias) hot-spot of Gansbaai. Marine biologist, Alison Towner and her team from Marine Dynamics and the Dyer Island Conservation Trust, investigated when liverless white shark carcasses washed up on the shores of Gansbaai in May 2017 and July 2020.

Although orcas were never recorded killing white sharks in False Bay, white shark sightings have decreased dramatically in both False Bay and Gansbaai.

White sharks and sevengills share many of the same prey, including seals, other sharks and rays, and bony fish. However, they appear to hunt in different areas or at different times. Research by Engelbrecht and Dr Kock has found that sevengills are nocturnal hunters. By day, they may rest under the shelter and protection of the shallow kelp forest, venturing into deeper, open waters at night, where they are less conspicuous to prey, and less likely to fall prey to white sharks, False Bay’s charismatic apex predator.

In contrast to the lesser studied sevengill, white shark movements in False Bay had been relatively well-documented and found to be rather predictable… until recently. Dr Kock has tagged and tracked the movements of white sharks in False Bay for many years. Her research has found that white sharks would typically spend the winter feeding on young seal pups at Seal Island, and in summer, they would move to the inshore areas to take advantage of migratory fish and other shark and ray species.

However, since the first visit of Port and Starboard to False Bay in 2015 (and their sevengill shark liver feast), Shark Spotters, a shark safety and research organisation, and local fishermen reported fewer white shark sightings along the inshore areas during summer too. Cage-diving operators became concerned at the dwindling numbers at Seal Island, in the historically peak winter season.

With sevengills absent from Miller’s Point and white sharks no longer enthused by the buffet on offer at Seal Island, by 2018, Scuba divers and cage-diving operators were becoming very despondent. No sharks, no business. Researchers and conservationists became concerned too. No top predatory sharks, no balanced ecosystem.

Just as the last glimmer of hope was fading, there was an unexpected turn of events for Seal Island shark ecotourism. Sevengill sharks began tugging on bait lines and investigating awkwardly-caged tourists around the diving boats.

My Masters research revealed that seals form an important part of the sevengill shark diet. In fact, there appears to be a higher proportion of seal in the diet of sevengills than in that of white sharks. This is likely as a result of sevengills eating seals all year round, while white sharks feed on seals seasonally. Sevengill sharks appeared to be taking advantage of the white shark’s infrequent visits to Seal Island, as they could exploit an abundant prey source, Cape fur seals (Arctocephalus pusillus pusillus), without the potential threat or competition from white sharks.

Although cage-divers wait in hope to see the majestic great white, they have been enjoying visits from the humble sevengill shark, with their delightful grin and a face resembling a dirty oven-mitt. Seal Island will, however, always be the territory of the legendary white shark, and it is anybody’s guess as to when they may return to their kingdom.

The ocean and marine life are incredibly complex and dynamic. Never static, never predictable, always fascinating. Ironically, what was expected to be a refuge area for sevengills, turned out to be a place where many were killed. To add to the irony, sevengill sharks now occupied the territory of white sharks (the predators they were likely seeking refuge from in the first place). Although shark-specialist orcas are well documented elsewhere in the world, we (and perhaps the sharks themselves) never expected any animal to scare off a great white.

There are no conclusive answers as to why the interactions and dynamics between top predatory sharks have changed over the years. Nor is it clear to what degree the increased presence of the super-predatory orcas may have played a part. It would be ignorant to expect a simple answer and to assume humans have no role to play in this. As much as we cannot discount the orcas’ impact, a combination of factors are likely influencing the presence of predatory sharks and orcas in the bay.

‘Flake and chips’

One such theory is that persistent offshore commercial long-line fishing is depleting much of the orca’s offshore shark prey, while inshore shark fishing could be depleting some of the key prey species for white sharks. The inshore shark fishery in South Africa targets predominantly soupfin/tope (Galeorhinus galeus) and smoothhound (Mustelus mustelus) sharks, with the meat sold as “flake” and chips in Australia.

Most consumers are unaware they are eating shark, and there is no legal requirement that it be sold by its actual name. The fishing of tope sharks is now illegal in Australian waters where stocks have been depleted. Fisheries have turned to South Africa, with detrimental effects to our stocks and the entire False Bay ecosystem.

The ocean has no fences, no walls, no boundaries. If a particular habitat ceases to be favourable for whatever reason, be it a lack of prey, or threats from predators or people, animals move, adapt or die.

I desperately hope to see white and sevengill sharks return to False Bay soon. Not only for the sake of the ecotourism that relies on their presence, but for the imperative role they play in maintaining the area’s ecology.

- Leigh de Necker is a marine biologist, aquarist and commercial diver at the Two Oceans Aquarium. She has completed her Master of Science (MSc) degree where she researched the feeding habits of broadnose sevengill and great white sharks in False Bay, South Africa. De Necker was one of seven winners in a recent writing competition on sharks and rays run by Roving Reporters. The competition was supported by WildOceans, a programme of the WildTrust, which facilitated access to conservation-minded youth keen to share their passion and develop writing skills with mentorship from Roving Reporters. The opinions and views expressed in this Ocean Watch series are not necessarily those of the WildTrust.

Now read… In deep: From barbel fishing to basking sharks