A worldwide nurdle search spanning six continents is underway, write Jared Sumar and Fred Kockott

First published by Sunday Tribune

- Over 350 million tonnes of plastic was produced in 2018 – more than the total weight of the human population.

- Recent research indicates that Durban has the worst nurdle-infested beaches in the world.

- Plastic producers must implement best practice measures to prevent pellet loss.

Nurdles are small plastic pellets that are melted down to make most plastic products. They are easily spilled and lost to the environment if not handled carefully. Once in the environment they are hard to remove and adsorb toxins.

Nurdles look a lot like fish eggs, which many species eat.

They have been found in fish, seabirds and turtles.

Not only does the plastic itself cause a problem for wildlife, but nurdles host toxic chemical and biological contaminants, said Jasper Hamlet, organiser of the Great Nurdle Hunt, an initiative to map the plastic pellet pollution globally.

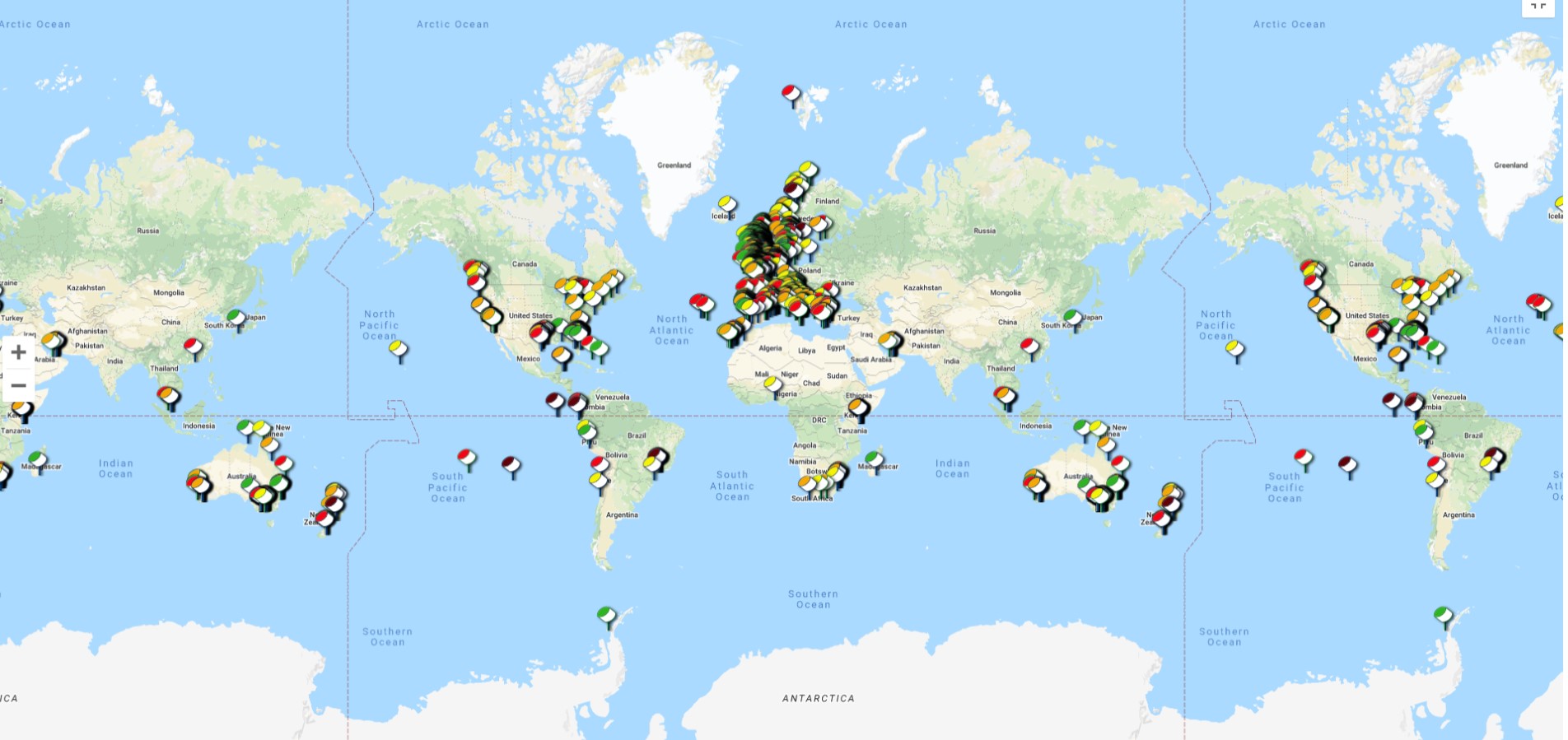

Tthe 10-day hunt aims to collate data to show governments and the plastic industry the scale of the pellet pollution problem. It receives support from the UK-based environmental charity, Fidra and other ocean conservation networks.

“We need to make sure pellets are handled responsibly by plastic pellet producers, by transport companies and by businesses using pellets to make plastic products. Action is needed throughout the supply chain by those handling nurdles to stop this form of microplastic pollution,’’ said Hamlet.

‘Ineffective’

Hamlet said some producers in the plastics industry have implemented best practice measures to prevent pellet loss. But “uptake of this voluntary solution has been low and the current system doesn’t have any checks in place to make sure it is applied effectively”.

South African oceanographic specialist, Lisa Guastella said nurdles escaped at almost all phases of the industrial process: when they are produced, transported between sites, manufactured into products and during recycling.

Massive cargo spills, including the 2018 incident in Durban, have added to the problem.

Some have described the Durban spill as among the worst ecological disasters to have affected oceans.

Disaster

Guastella’s research shows that billions of nurdles from the Durban spill entered the Agulhas current, polluting South Africa’s east coast and entering the South West Indian Ocean gyre.

Ultimately, nurdles from the spill ended up on beaches on the other side of the world, including in Perth, Australia.

Guastella blamed continuing spills from local factories for making Durban’s beaches among the worst nurdle-infested in the world.

“As the nurdles are tiny (as small as lentils) and mostly clear in colour, many people do not notice them until the they start looking in the sand,” said Guastella.

She is among environmentalists collecting and collating data for this year’s Great Nurdle Hunt, which ends on 22 March.

What to do?

To take part in the hunt, people should head to a beach or waterway and report their findings – the number of nurdles they see or collect – to www.nurdlehunt.org.uk. This data will be added to an online map, which will chart the scale of this plastic pollution and show that people worldwide care about the problem.

For tips to help you hunt, visit www.nurdlehunt.org.uk. – Roving Reporters

Journalists are trained to answer six key questions: Who, What, Where, When Why, and How. >> Click here to read about the 5 W’s and H of Roving Reporters.

Difficult choices must be made about how we use natural resources. But these choices need to be well informed if we are to do the least harm.

This requires citizens have a clear picture of what is happening on the ground. There are too many vested interests at play to leave things entirely to officials, elected or otherwise.

Keeping people in office on their toes and holding powerful interests, including NGOs, to account is an important role of the press.

Unfortunately, the media’s ability to do its job in South Africa has been hollowed away by the decline of traditional advertising support and readerships in the face of online technology.

Some papers have closed down, others are a pale shadow of their former selves; everywhere staff are stretched or juniorised.

Press standards have declined and false news abounds. Barring a few exceptions, reporting in the mainstream media is increasingly superficial. Yet a strong appetite remains for credible news, especially on environmental matters.

This underlines the need for Roving Reporters to grow its operations and develop a sustainable platform for environmental journalism training.

You can support our training progamme, Developing Enviromental Watchdogs by making a donation, no matter how small. Click here for further information.

If you have a story you would like Roving Reporters to cover, WhatsApp +27 83 277 8907. Include contact details of people we should speak to. Your message should also answer the question: Why should we care?