A sense of exclusion among coastal communities could hold back the drive to extend marine protected areas. Maxcine Kater reports on efforts to change that.

First published in the Daily Maverick 168 weekly newspaper.

When Steve Nkosi (not his real name), his family, and neighbours want fish to eat, it’s never a struggle to catch them.

They live in Mabibi, a remote community on a narrow stretch of land between the sea and lake Sibaya, in northern KwaZulu-Natal.

Fish are abundant here, partly because commercial fishing is not allowed.

“We mostly catch pompanos and blacktails. We also harvest mussels,” he said.

Mabibi falls within a Marine Protected Area (MPA) where regulations for inshore and offshore areas and designated zones restrict fishing practices or equipment or bar entry to fishing vessels. It’s part of the iSimangaliso Wetland Park, a UNESCO World Heritage Site that attracts tourists from far and wide. Many stay in guest lodges in the area, providing jobs for some of Nkosi’s neighbours in a part of the country where formal employment is scarce.

But, as tangible as these benefits are, many people in Mabibi and elsewhere in the northern parts of the park felt excluded, said Nkosi.

Some feel that regulations geared to protecting the environment in the iSimangaliso MPA restrict them from harvesting natural resources, as their families have done for many generations.

It’s a view widely expressed during interviews in the Kosi Bay area in 2011 and 2012 after the jailing for five years of 54-year-old Makotikoti Zikhali, found guilty of killing an endangered loggerhead turtle.

In the dune forest of Enkovukeni – a pristine peninsula of land between the Indian ocean and the Kosi Bay lake system – Simo Ngubane said: “That jail sentence was wrong. Yes, it’s not right to kill a turtle. They are vulnerable. We all know that, but some people kill them for food, just like people here are also eat monkeys.”

“We do not kill monkeys because we do not want them here,” he said, pointing into the trees. “We, the people of Enkovukeni, know animals, we live with them, protect them.”

Ten years on, little has changed for people of Enkovukeni where people have lived closely with nature since before Vasco da Gama sailed by. Few have benefited directly from living within a world heritage site, so talk of the wonders of MPAs means little to them.

But in other areas of the park, local communities have started to see benefits, particularly in jobs created by tourism enterprises.

Nkosi, who asked not to be identified lest it affected his job with an environmental organisation, said education would help people understand why MPAs are needed – and how they can, and do, benefit from them.

“Researchers should come to educate people, speaking to them in their home languages. If researchers came down and told the people that in 2050 there would be more plastic in the ocean than fish, the community would understand and try to help. They would think about their children and their grandchildren’s future,” said Nkosi. “These communities have been around for hundreds of years – before the notion of MPAs was even a thing,”

Marine landscape

MPAs have increasingly become part of the South African marine landscape. The country’s first was established at Tsitsikamma, in the Eastern Cape, in 1964. More followed over the years as a way to protect biodiversity, support ecotourism and improve stocks of commercially important fish species. In 2019 a further 20 MPAs were added, bringing the total to 42 (including those around Prince Edward Island).

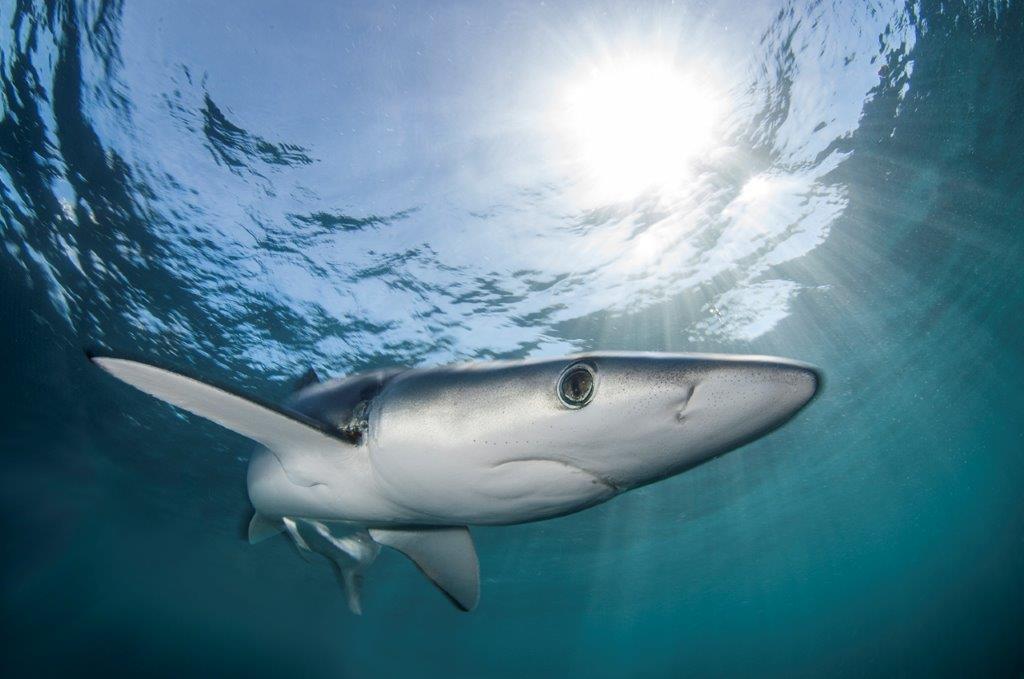

Ecologists view MPAs as an important tool for protecting the natural environment and worldwide there are growing calls to expand existing MPAs or to proclaim new ones.

Also, some MPAs protect nurseries and spawning sites for many fish species, letting populations increase and spill over into other areas which may not be protected. For example, species such as the roman in the Goukamma MPA have increased dramatically and are now supporting nearby fisheries.

Awareness

Dr Judy Mann, a conservation strategist with the SA Association for Marine Biological Research, and several partners, recently launched an annual Africa MPA Day. The day, held on 1 August aims to generate popular support for, and awareness of MPAs.

“We need to highlight the important role marine protected areas play in ensuring healthy marine life,” said Mann. “But we need to look beyond fauna and flora within the MPAs, and understand the benefits to nearby communities, such as the role of MPAs in attracting tourists, creating jobs for local people.”

But these efforts, she said, were hampered, on the one hand, by widespread public ignorance of MPAs, and on the other by a sense among many people living within or near protected areas that they had been left out of the decision-making process.

“MPAs also preserve our cultural heritage,” said Mann. Many people use the ocean for healing and spiritual practices. MPAs provide safe spaces for this, she said.

Coelacanths

The oceans remind us of our ancient links to the natural world, such as discovery of living coelacanths – on earth since the days of the dinosaurs.

Before the first coelacanth discovery, in the Eastern Cape in 1938, the science world thought this prehistoric fish – “Old Four Legs” as dubbed at the time – only existed in fossilized form.

Since then, they have been found in the Comoros, Tanzania, Kenya, Mozambique, Madagascar and in deep canyons in iSimangaliso – a discovery that gave rise to the African Coelacanth Ecosystem Programme. The multi-disciplinary research programme aims to ensure South Africa has in-depth knowledge of our east coast marine and coastal environment and its resources.

Hurdles

While the case for MPAs is strong, the call for more, or extensions and improvements to the management of existing protected areas, face a number of hurdles. These include:

- Public ignorance. Research by Mann found that four in every five visitors to Durban’s uShaka Sea World could not name a single MPA in South Africa; and

- The sense of exclusion experienced by people who live in or near MPAs but cannot see how it benefits them. Many feel they were not consulted when MPAs were established and that laws were imposed on them, preventing them from pursuing age-old fishing practices.

Nutrition

Makeba was born in 1969 in Ntubeni, on the Wild Coast, in what would later become the Dwesa-Cwebe MPA. She remembers her parents harvesting mussels to feed the family. “Our fathers would go fishing and we would know that day that supper would be a nutritious meal. We would look at the moon; when it was full moon we would eat the whole week and be happy eating mussels in different ways,” she said. The moon, of course, determines the tides and when it was best to pick mussels.

Makeba – who also asked that her real name not be used lest she be victimised – said her parents knew how to swim. They would catch crayfish and abalone which they would sometimes sell to tourists to earn cash.

Frustrations

But over the years things changed for the worse, she said.

The former Transkei government decreed the Dwesa-Cwebe a marine reserve in 1991 under the Transkei Nature Conservation Act and it was re-proclaimed under the Marine Living Resources Act of 1998. The Department of Forestry, Fisheries and the Environment confirmed that access to the reserve was controlled under the Act.

Makeba said the “new system” that required permits to fish in the Dwesa-Cwebe MPA “caused a lot of frustrations to our people”.

“Generations and generations have been making a living using the ocean and now the government has discovered a different way of doing things. For someone to go to the ocean there must be a permit. The permit was not easy to get. You would have to register and they (permits) would go get made in East London and you get them some other time,” said Makeba.

She said people were afraid to fish or harvest from the sea without a permit as they risked arrest by the reserve’s guards.

Permits

However, the department denied it was onerous for locals to get permits. “Permits are free for community members and they do not need to go to East London. While it is true that department officials are based in East London, these officials travel to visit and service the communities whenever there is a need to do so,” said department spokesman Zolile Nqayi.

They were working to make things easier for locals to get permits, he said.

“The department is using electronic means, such as emails, to make it easy for fishing cooperatives to apply for fishing permits and the permit is valid for one year. Officials do visit the cooperatives to assist them to apply as they do not have facilities, such as computers. The plan is to strengthen the electronic means of application,” said Nqayi.

Bag limits

But it was not only strict limits on harvesting seafood, including particular species and daily bag limits and the (disputed) difficulties around getting permits that irked Makeba. The restrictions had cultural and medicinal consequences too. “Sometimes when your body is not feeling well, we would go to the ocean and bring pots and boil water there by the coast under the trees. When you were done you would enema yourself with the syringe and clean your digestive system. The ocean was also healing us,” she said.

Makeba said villagers were reluctant to go down to the sea to seek cures because they feared trouble with the guards. She felt the government should have discussed the regulations with the community before imposing measures that separated people from the sea.

Access

But Nqayi insisted that the Dwesa-Cwebe community had a right of access to the protected area, although all activities within it were governed by the National Environmental Management: Protected Areas Act. Provided they had a permit, locals could fish in the MPA. And so long as they could confirm (with the assistance of traditional leaders) that they were members of the Dwesa-Cwebe community, they were given the opportunity to harvest thatching grass and reeds under a natural resource use plan.

There were limits, however. “Grazing of domestic animals within the reserve is not allowed as per the Act,” said Nqayi.

Benefits

Nokuthula Ngubane, who lives near the ocean and works at Sodwana Bay in the iSimangaliso MPA, sees pros and cons in living in or near an MPA.

“The good thing I can say about staying near an MPA is that I don’t have to pay for any of the attractions. I stay 10 minutes away from the ocean and I just walk there to swim and enjoy the beauty of the ocean freely, I also get to see turtles and how they give birth and get to learn more about them,” said Ngubane, who works for WildOceans, part of WildTrust, the environmental NGO.

Ngubane said that living within an MPA she had let her learn a lot about turtles.

“I am very happy that I can distinguish the different species of turtles. I consider myself lucky that I get to see loggerhead or leatherback turtles when they come to nest,” she said. “And, as I stay in a rural area, the ocean provides a way of sustaining our families since we can fish to eat or sell.”

People’s appreciation of MPAs also helped counter wildlife crime – as did involving them in conservation efforts, said Ngubane.

Turtle monitors

For example, in northern iSimangaliso, people living in the park, including at Mabibi, are employed as turtle monitors during the nesting season, from October through to January.

“They help authorities educate people about the importance of protecting turtles,” said Agrippa Shange, a tourism and development consultant from Bhanga Nek, between the ocean and the third Kosi Bay lake.

“It’s a very effective programme that has been running for more than 50 years,” said Shange. But isolated incidents of poaching still happened, he said.

Shange said that it was difficult to measure the level of turtle poaching, or who was responsible.

“It’s so easy for these incidents to go by undetected,” he said. “But last season two loggerhead turtles were killed near Kosi Bay mouth. I don’t know of any other cases.”

He agreed with Ngubane that for MPAs to be effective, they had to be adequately policed.

“People can just come and harvest illegally. Many use destructive fishing methods and some catch juvenile fish since they don’t know how to catch the fish according to sizes because the monitors are no longer there to protect the area,” said Ngubane.

Patrols

Musa Mntambo, spokesman for Ezemvelo KZN Wildlife, the custodians of the iSimangaliso Wetland Park, said manned stations along the coast, at Mapelane, St Lucia, Cape Vidal, Sodwana and Bhanga Nek, secured the protection of the MPA.

Welly Qwabe, a marine biologist with Wildoceans who works in the iSimangaliso MPA, said the stations were run by a total of two senior field rangers, five principle field rangers, five compliance managers and 31 field rangers. They patrolled during the day and, when required, at night to enforce conservation laws.

iSimangaliso beaches are mostly characterized by sand dunes, with limited development near to the shore. This, said Qwabe, provided a home, and natural protection for the animals that lived near the shoreline, as well as ideal nesting grounds for turtles.

The Kosi Bay area is also famed for its traditional, woven fish traps, in use for well over 700 years. Each fish kraal is carefully regulated, with the tribal authority granting families the right to fish in a specific area. The kraals reflect the deep connection the people of the area have with the ocean and it provides families with a source of food and income.

Future

As part of efforts to increase ocean protection, the recently formed Youth4MPAs has grown a countrywide coastal network, from KwaZulu-Natal to Cape Town, to promote the benefits of MPAs.

It’s an ongoing awareness movement to foster lifelong appreciation and protection of our oceans, said Youth4MPAs spokesperson, Merrisa Naidoo. “The reality is, without our contribution toward ocean conservation, the majority of marine life faces an uncertain future.”

“And without a healthy marine ecosystem we too face an uncertain future. Young people owe it to themselves and the future generations to create a better tomorrow,” said Naidoo. – Additional reporting, Fred Kockott, Roving Reporters

- Maxcine Kater is a 22-year old writer. She recently graduated with an honours degree in Marine Biology from the University of KwaZulu-Natal. This story forms part of Roving Reporters biodiversity reporting project supported by the Earth Journalism Network.

Now read… A lot on their plate: Sea’s custodians must do more