“We are wasting our resources conserving species in the wrong places with inadequate space, all in efforts to tick a box that we have conserved areas.”

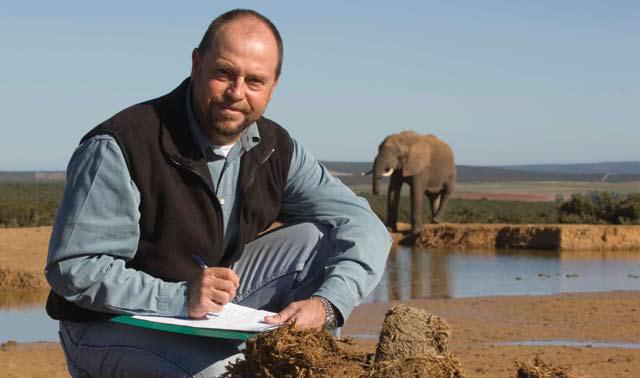

Globally there are nearly 240,000 protected areas, yet we have a growing number of endangered species. This conundrum troubles leading conservation ecologist, Professor Graham Kerley.

by Maxcine Kater for Roving Reporters

“Why are you trying to conserve cows in a forest?” Graham Kerley once asked a panel of European conservation scientists.

Kerley, a zoologist fascinated by evolutionary biology, was being interviewed for a Marie Curie Fellowship. He questioned why bison, which, much like domestic cows are bulk eaters of grass, were confined to European forests. He posed this question as a background to his proposed research into ecological restoration.

The European bison (Bison bonasus), is traditionally managed as a forest species, says Kerley. This is despite its evolutionary background, dental morphology, behaviour, and diet characteristics of a grazing species that thrives in open, grass-rich habitats.

‘Refugee species’

The ensuing Fellowship at the Polish Academy of Sciences’ Mammal Research Institute fueled Kerley’s interest in the subject, ultimately leading him to develop his “refugee species” concept.

Refugee species are those that can no longer access optimal habitats, resulting in decreased fitness and density. These animals become constrained by habitat and resource limits forced on them, with attendant conservation risks, says Kerley.

Kerley provided insight into this at the 11th Oppenheimer Research Conference that took place in Johannesburg from the 5th – 7th October.

In his presentation, The Protected Areas Paradox and Refugee Species Concept called for a more balanced approach to conservation – one that not only treats nature with respect by more equitably sharing the natural environment, but also learns valuable lessons from mistakes made in conservation.

Fragmentary

While a report from Statistics South Africa (Stats SA), released in October last year, states that the country’s terrestrial protected areas – 1581 of them according to SANParks – are growing at a healthy rate, Kerley reckons that aside from big reserves such as Kruger National Park, Kalahari Gemsbok National Park, iSimangaliso Wetland Park, Addo Elephant National Park and Hluhluwe-iMfolozi Park, most other protected areas, are far too small – 100 hectares or less. Few are suited to promoting large scale biodiversity and ecological restoration, says Kerley.

And historically, it is mountainous, barren, and rocky landscapes, where it’s hard for people to live or farm, that have been set aside for conservation, says Kerley.

In retrospect, we have pursued a piecemeal, fragmentary approach to the establishment of protected areas, which has clearly not guaranteed biodiversity protection, he says.

This has been a potential waste of money and resources, a vain attempt, or worse, paying lip service to conservation, argues Kerley.

“Humanity is so intricately linked to biodiversity we should not give nature the landscape rejects,” he says.

His message: “We are only fooling ourselves. Wasting our resources conserving species in the wrong places with inadequate space, all in efforts to tick a box that we have conserved areas.”

And understanding the evolutionary background of the species is necessary to avoid making more mistakes in conserving species, says Kerley. This includes the breeding of Cape mountain zebra in grass-poor habitats and confining Knysa elephant populations to suboptimal habitats.

Practical solutions

Kerley’s desire to find practical solutions to these conservation problems led him establish the Centre for African Conservation Ecology at the Nelson Mandela University in Gqeberha, 30 years ago.

The Centre has trained many young scientists while flying the flag for conservation on the continent, shifting attitudes away from a Eurocentric view of conservation.

Kerley points that the Nelson Mandela University campus has a reserve area of 5,3 square kilometres that is home to seven species of ungulate (hoofed mammals) – these being blue and grey duiker, Cape grysbok, springbok, bushbuck, bushpig, red hartebeest and zebra – whereas the entire North American continent has only 13 ungulate species.

Inspiration

Kerley hopes that lessons learned at the Oppenheimer Research Conference will help improve appreciation of the mistakes in conservation and spark an exchange of ideas about conservation, particularly among the younger generation.

“Our society desperately needs motivated young people with a thirst to better understand our world,” says Kerley who, in his childhood days, was inspired by documentary maker and broadcaster, David Attenborough.

“I was very fortunate that, at six years old, I was exposed to the David Attenborough Zoo Quest series on TV. But, as a youngster I never knew there was such a thing as a biologist, that you could develop a career studying animals. Or that you could help conserve them” He emphasizes the need to inspire young people to take up what is one of the biggest challenges of our times – the biodiversity crisis.

Some 50 years later, after three decades of zoology studies, Kerley hosted Attenborough at the Centre for African Conservation Ecology, inspired by the man’s teachings, including this dictum: Nature once determined how we survive… Now we determine how nature survives!

This story, commissioned by Jive Media Africa, was first published by Daily Maverick and forms part of Roving Reporters Game Changers series. It is free to republish provided the story is used without changes to the text, including captions. It must also include the Roving Reporters story byline and a link back to this post.

- Maxcine Kater is a young scientist interning at the Department of the Fisheries, Forestry and the Environment. She is also taking part in an environmental investigative journalism initiative established with the support of the Henry Nxumalo Foundation.