Two tiny loggerhead hatchlings look set to become an educational centrepiece at uShaka Marine World after their rescue off Durban beaches

recently. Sabelo Nsele and Nomfundo Xolo report

- First published in Daily News

At first, Durban lifeguard Owen Hlongwa had no idea what the “limp lump of something” that had washed up on uShaka Beach was. Then he saw faint signs of life.

It was a baby loggerhead turtle, matchbox size.

“I put it in a bucket of seawater and it started reviving,” said Hlongwa. Soon afterwards a second hatchling, slightly injured, also washed ashore.

Both were taken to uShaka Sea World where they were revived in a specially designed hospital tank by senior aquarist, Karin Fivaz. At just more than 40mm, the hatchlings were estimated to be two weeks old.

Because it was the week of Valentine’sDay , the slightly injured hatchling was named Valentine. The other was called Ula, which is Irish for jewel of the sea.

Roving Reporters recently visited uShaka to start monitoring the rehabilitation process.

The first video shoot shows the two hatchlings floating aimlessly about their hospital tank mostly fin-by-fin, occasionally experiencing head-to-head collisions.

Vulnerable

“It takes loggerheads up to six months to a year to learn to dive,” explained Fivaz. “This makes the young turtles very vulnerable to predators.”

Fivaz said it was likely the hatchlings had drifted down the warm Agulhas current from protected nesting grounds around Bhanga Nek, Black Rock, Sodwana or St Lucia in the iSimangaliso World Heritage site, more than 350km north of Durban.

Fivaz gave insight into the epic journey the hatchlings would have faced. After emerging from eggs on a nesting beach far north, the hatchlings would have run the gauntlet of a multi-predator feeding frenzy as they dashed to the shore – a spectacle worth witnessing. Besides thousands of ghost crabs and hundreds of seagulls and terns, many other predators feed on hatchlings including jackals, dogs and mongooses. The odds of hatchlings reaching the shore are stacked against them. Those that do make it face greater danger as they enter the ocean.

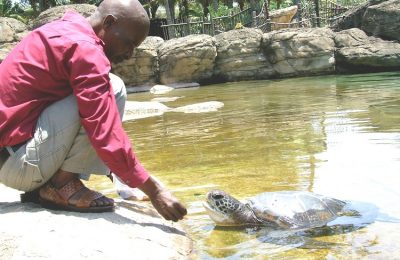

The story of convicted turtle poacher turned sculptor, Makotikoti Zikhali, pictured above, inspired several Durban University of Technology journalism students to learn about turtles and ocean life. Students work on this story marked the start of Roving Reporters environmental journalism programme.

Challenges

In shallow waters, they are preyed on by all kinds of fish, including sharks. Once out in the ocean deep, a whole new set of challenges and dangers lurk – above and below the surface.

This includes larger turtle eating fish, bigger sharks and birds, pollution and fishing trawlers.

Pollution is particularly a problem as turtles grow older . “They often mistake plastic bags for jellyfish,” said Fivaz.

This can block their digestive system, effectively starving them. Given all these dangers, a loggerhead’s chances of survival into adulthood are slim.

George Hughes, author of Between the Tides, in Search of Sea Turtles, puts the survival rate at 2 in a 1000.

In his chapter, How Hatchlings live and Die and Other Dangers, Hughes also tells how upwellings of cold water from the ocean deep exact a toll on loggerhead turtle hatchlings.

While turtles thrive in warm water of between 2026ºC, cold water renders hatchlings weak, unable to swim or feed. This often causes hatchlings to be blown ashore, as is likely to have happened to Ula and Valentine, who were finally tossed and twirled through Durban’s surf and spat out on the beach.

Valentine

For the first week, Valentine appeared to be recovering well, but has since died.

Citing either infection or its original injuries, uShaka staff said given Valentine’s tiny size it was hard to know the exact cause of death.

Ula, however, is gaining weight and is expected to fully recover, alongside another hatchling, Sam, that washed ashore on the Bluff on February 21.

Both hatchlings have since been moved from quarantine to tanks open to public viewing. Fivaz said that over the next 11months, Ula and Sam will be pampered with prawns, sardines and uShaka’s “gel food” (fish mulch, gelatine and vitamins), while its surviving brethren in the oceans grow up on a diet of algae, sea grass,

bluebottles and jellyfish.

Ula and Sam

Ula and Sam will be released back into the sea when they are a year old and about the size of a dinner plate.

Exactly what chance they will have of surviving in the ocean unaccustomed to many dangers at sea, is uncertain. But given that Ula and Sam will, by then, be able to dive and swim, Fivaz reckons they should have as much chance of evading predators as any other young turtle, irrespective of whether it has been raised in captivity or not.

“At least they will have been assured a year’s survival which is a good head start over hatchlings in the ocean,” said Fivaz.

Last year, uShaka rehabilitated five turtle hatchlings, all of which were successfully released.

“Unfortunately, they were still too small to be tagged, so we can only wonder where they are now,” said uShaka spokeswoman, Ann Kunz.

FEATURED IMAGE: These two loggerhead hatchlings in the hands of uShaka Marine World senior aquarist, Karin Fivaz, recently washed ashore on Durban’s beachfront. One has since died, but the other, now named Ula (jewel of the sea), is recovering well alongside a third turtle hatchling, Sam, that had washed up on the Bluff. Photo: Nomfundo Xolo.

Now read

Durban University of Technology graduates, Nomdundo Xolo and Sabelo Nsele, worked on this series stories as part Roving Reporters environmental journalism training programme. Click here to view the pdf of the stories published by the Daily News.