Black communities lived in harmony with nature centuries before parks were created as “fortresses to protect nature” – an issue many conservationists choose to ignore, writes Merlyn Nomusa Nkomo.

Conservation globally is a challenging battle. Movements against climate change, plastic pollution and deforestation in the Amazon are on the rise. So to are ground-breaking research and futuristic interventions, and yet the natural world is burning. Nowhere else is this more evident and an uphill battle than in Africa and this is why.

I am an aspirant ornithologist and a conservation leader pursing a masters in Conservation Biology, one of only two black people in my class. On my first day of joining the class, while getting a coffee at the kitchenette, a friendly black South African passed the comment, “so you’re with the rich kids” after I had told her what department I was from.

Unfortunately, this is the prevailing stereotype not in South Africa but everywhere else. Conservation is a luxury, pursued by the rich and a field for the privileged. There is a huge gap and a disconnect; black people in Africa have accepted and now believe that the love of nature and wildlife is a “white thing” and white people believe black people do not love or know as much as they could about nature and wildlife.

Disconnect

There are few exceptions and places where this is changing but this is the prevailing system and has been since colonial times when parks were fortresses to protect nature from black communities that had lived with it in harmony for centuries before. The status quo cannot persist because it begs the question: who are we conserving Africa for if the majority is not part of or interested in the solution.

Why is conservation action yielding results in America and Europe far better than it is in Africa, where there is far greater opportunity, more protected land, more wildlife and more funds poured into projects? Other continents have real conservation wins, from species coming back from the brink of extinction to polluted river systems being restored and attitudes of people changing.

It is worth noting that these wins are few and far between, but they are wins nonetheless. Africa, on the other hand, deals with more poaching and environmental degradation with every year that passes. Africa has the youngest and fastest-growing population in the world and what we do today will set the pace and trajectory for the continent’s development.

Reality

A fundamental problem exists: conservation in its current form will not be effective in Africa. Impactful and effective conservation efforts cannot exclude systems thinking and behavioural change. It takes a lot more than scientific brilliance to influence behavioural change, it takes passion and dedication to see that the problem is fixed (provided the real problem is known).

For many of us, Africa was never a choice or an option on the map. Africa is not a dream of charismatic wildlife, golden savannas and swampy jungles with elusive creatures. It is a reality, not a dream we have attained; Africa chose us and it is the only option there is, as we have no place else.

Going to another continent, having a successful scientific career and solving the problems there, is not something we can aspire to, afford or even reach for. It is not realistic unless you want to be a nurse or be relegated into the care system of those continents to make good money to send home.

However, for hundreds in the west, Africa is a new chapter in their lives and it is within reach. It is affordable and they can pick any country or species to “find themselves or their passions in.” They find a job market that is ready and willing to assimilate them instead of building capacity and interest where it is needed.

Experience

I speak from experience. A summer internship for a British young lady lands her a managerial research position over a local graduate who interned in the same place for a year but has to give tours and host visitors to the facility. Organisations running volunteer projects targeted at giving internationals a green-tourism experience and university credits, while priced too high for a local student to afford and participate in. Even I tried to join these volunteer programs. Despite my endurance, I realised they would not accept me if I did not pay the amount upfront in American dollars, never mind the knowledge I had to offer or gain.

The conservation industry is not economically conducive for black people, more so in the African context. We all know that money should not be your motivator to get into this industry. At any rate, most people are not driven into this field for the money they can make.

White ceiling

This narrative, however, makes it seem like one cannot make a decent living from a career in conservation. But this is not true, as I have seen all around me, many professionals I know and interact with have even a better living standard than most people I know. There is a ceiling in conservation and everywhere you go it is white.

The opportunities to grow professionally are minimal, at least at the rate of our counterparts. Everyone knows that hardworking graduate friend who has been an intern for years working for peanuts. We all know how much harder we have to work to make the benchmark and qualify. Conservation is not a cheap field to be in (funny enough), it is expensive to get the right and appropriate gear, clothing and be at the right places.

I have been to week-long conferences were meal tickets were R200, that in itself excludes an entire demographic. It almost seems like Africa is the perfect destination for these meetings, just not the destination for the resolutions of these conferences. These are just a few examples that show how conservation is not yet inclusive, considerate and attune to the black African experience.

Spaces

A recent commentary on the South African Journal of Science titled “Why are black South African students less likely to consider studying biological sciences?” was published and has been stirring a lot of negative reactions from black people I know all over the country. The problem is known and fortunately in our lifetime, spaces are being created for these conversations to be had.

There have also been peer-reviewed publications reporting the racial bias that exists. It is important to get the voices of Africans themselves in these conversations. It cannot be another situation of Africa’s history told from a non-African worldview. A simple example; the recently published commentary asks black students their pet ownership history; if they believe people evolved from apes and other questions that do not relate in any way to the black African experience.

The study then uses that as a measure of why one would choose or chose not to pursue a career in conservation. Questions about social inequality versus the environment and national parks versus giving land to the poor are asked to members of a black community with high levels of poverty, homelessness and a national debate on land ownership as a decider of whether or not they value wildlife. Why not ask how old they were when they first visited a national park?

Superficial

Even in the most integrated campuses, people do not relate to or understand the black experience because of superficial interactions that occur every day. Black people keep filling a role that makes them belong and white people stay continually believing that their lived experience, like relationships with pets (other than wealth and financial security), is the standard and everyone else relates to the world and makes decisions based on the same worldviews.

|A lot needs to be done, ask your black colleagues how. They know best why biological sciences are least chosen by those like themselves. They know how to make the space more inclusive because they each have stories and personal experiences. Much like the time in my internship when my initiative of having local children come to the facility where I worked was diverted. It was meant to be a children’s bird conservation club that I would run and create material for, to bring different groups of children together. My boss told me at the last minute that, for security reasons, she would be the one to invite the children (via email) and was concerned the local children would use the opportunity to tell their parents about the property so they would come and rob them at night. This property had an electrified fence, a high gate with codes and numerous dogs and these kids who were, I suppose, taught by their parents to take advantage of such unexpected invitations to learn about nature, would not miss the chance to figure a way to break into this fortress.

Language

Ask your colleagues how to do things better, how to be better and relevant for the times because communities out there are excluded this way from conservation. Like Professor Drew Lanham just said during a webinar, “if you do not have time for my issues, I do not have time for yours.”

Most conservationists do not even bother to learn local languages or pronounce things right and they assume their surveys with people of a different language and culture are not on a superficial level. Almost all black folks in conservation identify as science communicators because we have to double up for this role and educate our community the way we know works.

I have mentored, presented, taught and trained countless individuals who never owned and cuddled pets and I have seen their lives change literally from one encounter or chat about vulture conservation. All this I do without a budget or benefactors, without colourful handouts and pamphlets.

Consequences

People do not care how much you know until they know how much you care. Conservation needs to decide what the primary focus is, publications and “discoveries in Africa?” travelling and working in remote and picturesque places? I believe this should take second place to solving the problems that will destroy it all for future generations. Like Pathisa Nyathi once said to an audience at a vulture talk, “keep frowning on African culture and your birds will be driven extinct by what you call myths and superstitions. Beliefs are as real as their consequences.”

The researcher who fell in love with Africa and her wildness from National Geographic films or at zoos and shows will have a different commitment to the problem than the one who knows the hunger of an elephant raid, one who herded cattle in a village were lions prowl at night and one who knows the true meaning of your life and next meal depending on the environment you live in.

- This article was first published by Ilizwe – a student operated publication based in Stellenbosch, South Africa.

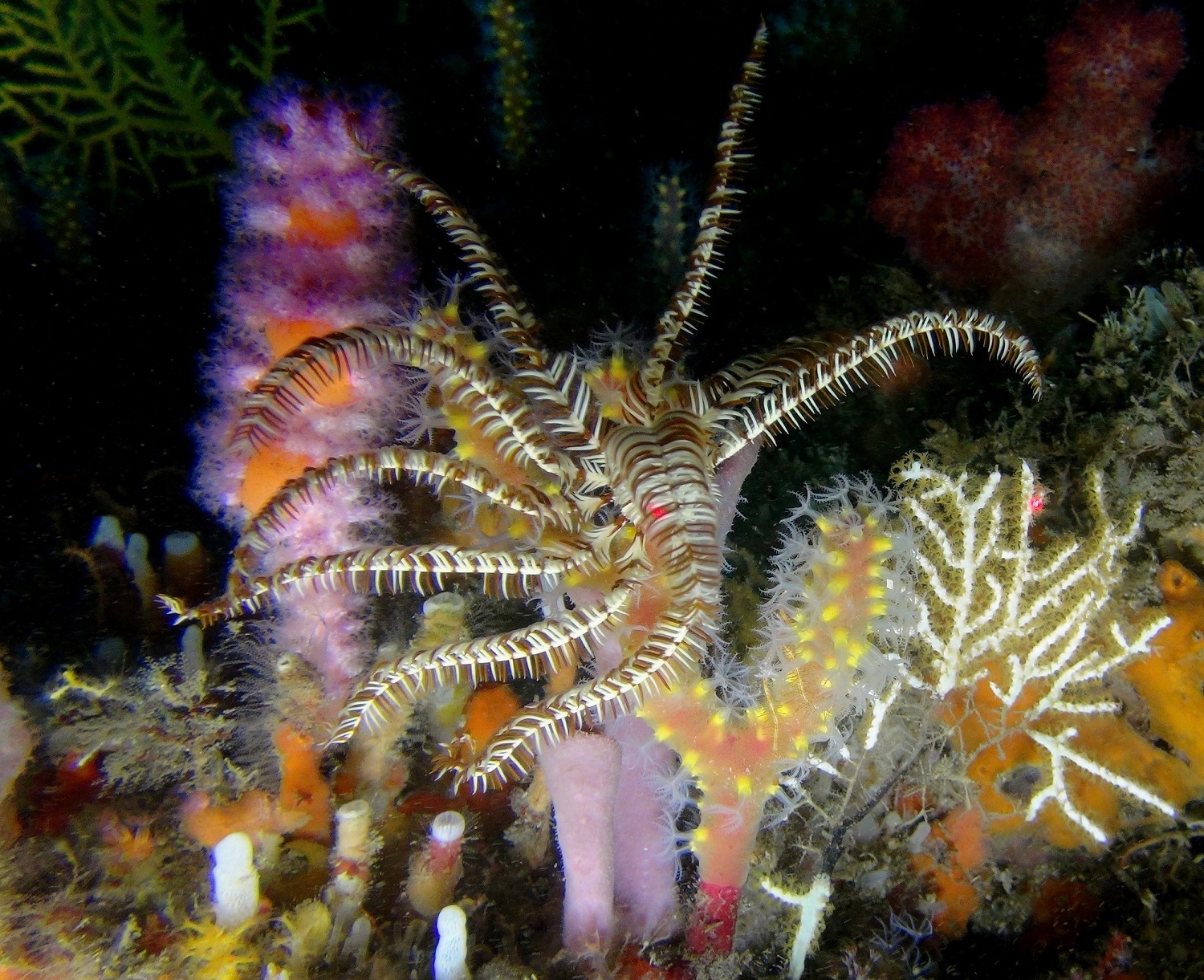

BANNER IMAGE

>> Now read: Involving more people in the ‘wild economy’ will make this world a better place

For too long, we’ve got it wrong when it comes to conservation. Fortunately some, especially the young, are pointing us in the right direction, says Francois du Toit