Environmental scientists should step out of their silos if they want their research to make an impact, says Duncan MacFadyen, head of Oppenheimer Generations Research and Conservation.

Interviewed on the outcomes of last week’s 12th annual Oppenheimer Research Conference, MacFadyen said effective networking between scientists and decision makers from diverse backgrounds was vital to solving Africa’s environmental crises.

“So often, scientists work in silos,” said MacFadyen. “At an ornithological conference, you have all bird people talking to each other. You go to a herpetological conference, and it’s all reptile people talking.”

“The good thing about this annual conference is that it is multi-disciplinary,” said MacFadyen. “It breaks down those silos. It creates an opportunity for people working in different areas to work together – and this year it really happened,” said MacFadyen.

He said amid the stark assessments of the challenges Africa faces, this year’s edition of the conference was “refreshingly positive”.

“It was not just about the ‘world is heating up at a rapid pace, our habitats are shrinking, more and more species are becoming endangered, alien invasives are taking over, our waters are polluted’. It was also about what we are going to do about it all,” said MacFadyen.

“I saw soil people wanting to talk to climate change people. Mycorrhizal fungi people want to connect with the Madagascar lichen and bryophyte programme (which is using moss and other primitive plant species to monitor air pollution, climate change and biodiversity loss) … The networking that took place was significant and in line with this year’s theme: Science for Impact.”

Tangible outcomes

This level of networking was also “close to the hearts of the Oppenheimers who feel frustrated when science happens for the sake of science, especially when it costs a lot of money and a lot of time.”

“In opening the conference, Jonathan Oppenheimer made the point – and I totally agree with him – that so often scientists only talk to scientists,” said MacFadyen. “Papers get published, which is great. People complete their theses, which is great. This costs a lot of money, and takes a lot of time, but then the thesis gets put on a shelf and nobody reads it,” said MacFadyen.

This was not the kind of research that Oppenheimer Generations liked to support, said MacFadyen.

“So, a lot of the presentations at this year’s conference were about big programmes that have meaningful and tangible outcomes related to biodiversity loss and climate change, which as we all know is going to have huge impacts within our lifetimes,” said MacFadyen.

Startling figures

“It’s said that this has been the hottest year ever, already. There were figures thrown around that R800 billion (USD 42,5) is now needed annually for nature and conservation in Africa. This is a staggering amount of money,” said MacFadyen, referring to the latest “State of Finance for Nature” series of reports compiled by the United Nations Environment Programme. These reports quantify public and private finance flows to nature-based solutions to tackle global challenges related to biodiversity loss, land degradation and climate change.

The last annual report states that, globally, investments into nature-based solutions need to quickly ramp up to USD 384 billion a year by 2025, more than double the current US$ 154 billion a year, if we are to limit global warming to below 1.5°C, halt biodiversity loss and excessive land degradation.

Connections

Elaborating on the “science for impact” philosophy behind Oppenheimer Generations Research and Conservation (OGRC), MacFadyen said the conference was in the business of supporting research related to the economics, the social side and the ecological aspects of the “simultaneous equation between man and environment.”

“All of these dynamics are at interplay with each other. We can’t avoid or exclude any of them, but one thing scientists don’t always look at is the economics,” said MacFadyen.

“So, over and above scientists coming together from different walks of life, we also bring in government people and decision makers who can guide and implement policy… Solid science needs to be the base of good decision making, but science alone is not enough.”

Making that connection – between scientists and decision makers – was the very reason that OGRC exists, said MacFadyen.

Research grants

In addition to organising the annual conference, the OGRC hosts the monthly Tipping Points webinars that bring together thought-leaders and researchers to address key issues affecting development and the environment in Africa.

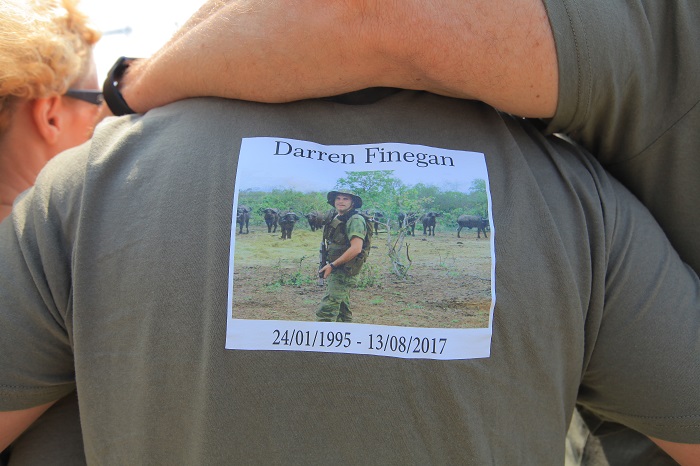

OGRC also runs a research grant scheme to help early-career scientists develop scientific solutions to African problems. Established five years ago, the Jennifer Ward Oppenheimer (JWO) research grant of US$ 150,000 (about R2,8 million) is awarded annually to an early career scientist in honour of the late Jennifer Ward Oppenheimer and her extensive contribution to, and passion for Africa, the environment, and science.

Great balls of moss

At this year’s conference, the 2023 JWO research grant was awarded to a Madagascan scientist, Dr Lova Marline to intensify her studies on how a unique group of lichens and bryophytes (mosses, liverworts and hornworts) could help monitor three major threats facing humanity and the global environment – air pollution, climate change and the biological diversity crisis.

Marline hopes to show how these primitive plant species could offer a new early-warning system, in a similar way that generations of coal miners once relied on canaries in cages to detect toxic or explosive gases. The birds, being more sensitive than humans, would die or get sick first, giving miners a chance to escape or put on protective breathing equipment. >> Click here to read more.

The winners of the previous JWO grants were:

Dr Elizabeth le Roux

2022 JWO WINNER

Le Roux’s research explores the complex interactions between plants, animals, cattle dung and people. It aims to align ecological processes and local livelihoods. As Le Roux observes, large herds of hungry domesticated cattle are often seen as a threat to the future of Africa’s shrinking wildlife conservation areas. But could it be that cattle and pastoral communities are part of the solution? >> Read more

-

- Le Roux is an assistant professor at the University of Aarhus in Denmark and a research fellow at the University of Pretoria.

Dr Gideon Idowu

2021 JWO WINNER

Idowu’s research helps policymakers and communities gain a better understanding of the effects of microplastics and chemical contaminants on people and the environment and helps mitigate the impact on current and future generations. It also explores how, through poorly enforced environmental laws, Africa contributes significantly to global marine plastic pollution, as well as the contamination of its own freshwater bodies upon which many rural populations depend for drinking water. >> Read more.

- Idowu is a lecturer and researcher at Nigeria’s Federal University of Technology Akure (Futa).

Bernard Coetzee

2020 JWO WINNER

Coetzee’s research aims to understand the impact of the use of artificial light in Africa and how it may increase vector disease transmission (malaria, zika virus, dengue fever). Mosquitos for example, cause an estimated 700,000 deaths globally per annum, and affect millions of people in Africa annually. His research also investigates the impact of artificial light on biodiversity. >> Read more.

- Coetzee is an Honorary Research Fellow at University of the Witwatersrand, based at Skukuza in the Kruger National Park.

Dr Hayley Clements

2019 JWO WINNER

Clements was the inaugural recipient of a JWO research grant that supported the development of a Biodiversity Intactness Index for Africa, through a continent-wide collaboration of biodiversity professionals. The project explores where and how biodiversity loss impacts human wellbeing, promoting understanding of where investing in nature can deliver net benefits for society.

It’s taken four years, 200 people and $150,000, but now, says Clements, “we have this phenomenal map that shows us the state of biodiversity across sub-Saharan Africa. It’s beautiful. It’s just really cool.” >> Read more.

- Clements is an interdisciplinary conservation scientist in African biodiversity at Stellenbosch University’s Centre for Sustainability Transitions.

- This story was produced with support from Jive Media Africa, the science communication partner to Oppenheimer Generations Research and Conservation.