A deeper, grassroots approach to conservation – and solid science – could stave off looming extinctions. Fred Kockott reports on some of the lessons (and offbeat tales) from the 12th annual Oppenheimer Research Conference

Apart from a skeleton at the Durban Natural Science Museum, a mummified head and foot at the Oxford Museum of Natural History in England and no doubt some bits and bobs in other collections, little remains of the dodo.

Even with all the remarkable strides in genetic engineering it seems unlikely the extinct bird will ever lift its flightless wings again.

Now, with humanity standing at the precipice of even greater environmental catastrophe, it is time to learn from mistakes of the past and turn ongoing conservation failures into success.

This was a key message arising from the 12th annual Oppenheimer Research Conference that took place in Midrand, South Africa from October 4 – 6.

The conference opened with a warning from 89-year-old anthropologist, Dr Jane Goodall, that time was running to turn the tide on environmental degradation.

“We are not only part of the natural world but depend on it for food water, air, everything. And in healthy ecosystems, all animals and plants are interconnected and have a role to play,” said Goodall.

“As one species after another disappears from that ecosystem, it will eventually collapse and it’s already happening,” warned Goodall.

This was due to a variety of reasons, including “a crazy belief that there can be unlimited economic development on a planet with finite natural resources and the growing human populations”.

Common sense

“Science, as well as common sense, clearly shows that if we carry on with business as usual, we are doomed,” said Goodall.

“Forests, wetlands, peatlands, grasslands, all of which store carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, are being destroyed, and habitats lost or fragmented,” said Goodall.

While herbicides and artificial fertilizers of industrial agriculture are having a devastating effect on biodiversity, killing the soil, huge volumes of industrial and household waste are polluting our rivers and oceans. Amid this all, unsustainable lifestyles make unrealistic demands on earth’s natural resources, driving many people in poverty, said Goodall.

“Take care”

She said when she began her study of chimpanzees in Tanzania in 1960, the Gombe National Park was part of the Equatorial Forest belt that stretched to the West Coast. 30 years on, Gombe was just a small island of forest.

“The hills were bare. The trees were gone. The over-farmed land was infertile. I realised then that unless we helped people make a living without destroying their environment, we couldn’t save chimpanzees, forests or anything else.”

This realisation gave rise to programmes such as Roots and Shoots and the Lake Tanganyika Catchment Reforestation and Education (TACARE) program – a bold and holistic approach to community-led conservation pioneered by the Jane Goodall Institute.

It has been a widespread success, ultimately creating sustainable livelihoods, promoting environmental protection, and driving significant social change not only in Tanzania, but other parts of central and eastern Africa.

“It all began by working closely with the surrounding communities, listening to their concerns and ideas, including restoring fertility to the soil,” said Goodall. “Fortunately more and more conservation groups have now come to realise just how important it is listen to the voices of the indigenous people who’ve been wise stewards of their land for hundreds of years.”

In her opening address, South Africa’s minister of International Relations and Cooperation, Naledi Pandor, said while the spectre of massive environmental disasters looms large, she felt privileged to attend a scientific event in which so many leading environmentalists sought solutions to Africa’s pressing environmental problems.

Pandor applauded the successful protection of endangered wildlife species in Africa, “some of which would possibly be extinct” if it had not been for the interventions of people like Goodall and Prof Carl Jones, a biologist from Wales, who during four decades of work on the Indian Ocean island of Mauritius, helped save five bird species from local extinction (the Mauritius kestrel, pink pigeon, echo parakeet, Rodrigues warbler and Rodrigues fody) as well as the Rodrigues Fruit Bat and three populations of reptiles (Guenther’s Gecko, Orange-tailed Skink and Round Island Boa).

Jones is a recipient of Indianapolis Prize, often dubbed the “Nobel prize” of conservation.

Jones’ plenary presentation, Lessons for the Dodo, provided insight into how easily humans can irreversibly damage an ecosystem and cause extinctions. The lesson from this “iconic lost species”, he said, was that it was only years after the dodo the dodo had become extinct, in 1662, that people “looked back and said ‘where’s the dodo gone?’.

“They then realised that the world was exhaustible, that we could deplete species, that they weren’t just there for us to take and take and take. Yes, it took a few more centuries before it became embedded in western consciousness that we were causing extinctions. But one can honestly say that it was on Mauritius, with the loss of the dodo, that we had the dawning of the modern conservation consciousness.”

He said it was a sobering wake-up call that has continued to catalyse conservation efforts to prevent the same happening to other species around the world.

On the chances of the dodo ever existing together, Jones said: “They’re working on it but I don’t think they have enough genetic material. What they will be doing is moving genes around, and come up with something that’s a chimera that will have some dodo in it. Most of the genome of the dodo still exists in other species, so who knows where all that’s going to go.”

Sounding the alarm

The opening session of the conference ended with another warning from Hector Magome, former head of conservation at South African National Parks (SANParks), that many of South Africa’s cash-strapped and sometimes poorly managed provincial parks, risk collapse.

Magome quoted a study published earlier this year that highlighted many difficulties facing the parks. These included a lack of funds, which meant four-fifths of budgets was spent on staff salaries; a dearth of conservation knowledge among senior staff; and political interference to the extent that it amounted to a “political takeover”.

He feared that parks in the provinces “may finally collapse”, mentioning the unchecked grazing of cattle in some Ezemvelo KZN Wildlife reserves and the burning of a community-owned lodge in Mthethomusha Game Reserve by people from within the self-same community.

“There is a very high likelihood that in future we will only have South African National Parks and Cape Nature … mainly because they generate 80% to 85% of their own money,” Magome said.

Africa’s Rhino populations – looking up

Magome also shared valuable insights he has gained in the rhino conservation sector. He said despite the increasingly bloody poaching conflict, the outlook for Africa’s future rhino populations was a lot more positive than most people believed. Read: Keen to save rhinos? Focus on their rear ends – not their horns.

Zombie apocalypse

In the conference’s third session, delegates got to hear of a massive effort to end a “zombie apocalypse” that has been playing itself out on Marion Island for more than a decade.

In their presentation, “Saving Marion Island’s seabirds – the world’s most important bird conservation project”, Mark D Anderson, the CEO of BirdLife South Africa and Mavuso Msimang, the chair of the Mouse-Free Marion Non-Profit Company, said up to 19 species Marion Islands birds faced extinction if the invasive rodents were not entirely annihilated from the island.

They gave details of the ambitious undertaking, the Mouse-Free Marion Project, to annihilate millions of House Mice which are endangering the long-term survival of seabirds and other native species on South Africa’s sub-Antarctic Marion Island. Thought to have been accidentally brought to Marion by sealers in the early 19th century, the mice have had a devastating impact on the ecology of the island by attacking and literally eating alive the chicks – and even adults – of both surface-nesting and burrowing seabirds.

New plans to rid the island of the mice requires a total of 600 tonnes of rodenticide to be distributed across the island over a two-year period. The funding target to launch the operation is US$25-million.

Will it happen and will it work? Mavuso and Anderson are confident it will. Read: Massacre at Marion: Mouse eradication project gathers pace.

Following the macabre sight of house mice feeding on albatross brains on Marion Island, delegates were treated to a visual spectacle from award-winning photographer and filmmaker Kim Wolhuter, the grandson of the late Harry Wolhuter, one of Kruger Park’s first rangers.

In 1904, while riding on horseback shortly after nightfall, two lions attacked Wolhuter. A tribute to Wolhuter snr. on the Siyabona Africa website, reads: “Toppled from his horse, one of lions seized him by the shoulder, and dragged him almost 100 metres, into the bush. At this point, the semi-conscious ranger managed to retrieve his sheath knife from his belt and stabbed the lion. The mortally wounded lion then dropped Wolhuter who managed to climb into a tree before the second lion came after him. Wolhuter believes he was saved by his dog, Bull, whose persistent barking at the second lion distracted it. Wolhuter’s assistants then arrived and carried him back to camp.”

More than a hundred years later, Wolhuter jnr, now an Emmy Award-winning filmmaker, walked alongside a wild cheetah mother and her young family for almost two years to unravel in intimate detail what it takes to turn tiny cubs into accomplished predators. The dramatic film footage formed the basis of David Attenborough’s acclaimed 2017 documentary: Cheetahs growing up fast.

At the screening, Wolhuter told the delegates, as he always does, that cheetahs, clearly have more patience with their young than humans do.

The next day, world renowned zoologist, Dr Gus Mills, gave a more scientific, but equally lively account of cheetah’s hunting behaviour, prey selection, the role they play in the food chain, and their relations with competitors and each other. This was based on a six year study of cheetahs in Kalahari. Read: Desert days — how cheetah (and hyena) man Gus Mills knocked the spots off the naysayers.

Staying on the subject of big cats, lion guru and ecologist, Prof Craig Packer, who has authored several books on lion conservation, shared his insights

in studying and documenting cases of major outbreaks of lions feeding on people in Tanzania and the error that accompanied them. As he observes, as human populations expand and lions’ prey dwindles, it is the poorest people — and hungriest lions— that continue to pay the price. Read: Lions and rural communities in a life-or-death battle for survival.

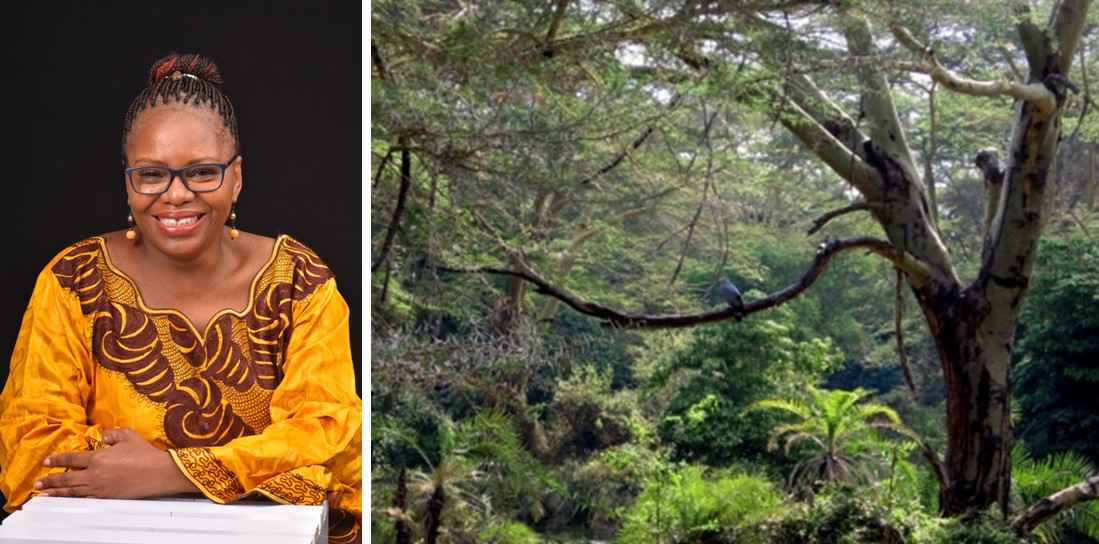

In another key presentation, Kenyan forest ecologist, Dr Doris Mutta, noted that Africa has about 640 million hectares of forest or woodlands of one sort or another — from mangroves to Afromontane forests, dryland forests, miombo woods, to the world’s second largest tropical rainforest, in the Congo basin. Together, these cover about one-fifth of Africa’s landmass and represent 16% of the world’s forest cover – a bulwark against climate change and environmental degradation.

Treasure troves

They are also a cornucopia of foodstuffs, seed varieties and plants with significant medicinal value.

Four in every five people worldwide depend on medicinal plants for their primary healthcare. But are Africa’s traditional healers, the source of many of these cures, benefitting? (Photo: Courtesy Ghanaweb.com | Wikimedia Commons)

Mutta, who has done a lot of research on traditional medicine and indigenous knowledge of medicinal plants, says Africa’s traditional healers have a vital role to protecting these treasure troves. Like Goodall, she calls for deeper engagement with people those who have lived amid these forests for generations.

“People living in or near forests are key players,” said Mutta. “They know what’s happening in the forest area and they know the value of that forest. They have indigenous knowledge on how to sustainably use the forest… for example, for food and medicine.”

But drawing on traditional knowledge can be hard to do.

“Some of the traditional healers and herbalists don’t tell scientists everything. They hold back some information as a trade secret. They say if I tell you everything, you’ll publish the information and together with prospectors from the north, the wazungu (Swahili for a white person), you will develop modern products and you’ll forget me. You’ll make money and I will remain in poverty,” says Mutta.

Mutta would like to see the development of an intellectual property system that ensures “knowledgeable people in our villages in biodiversity rich areas” feel safe and happy to share their knowledge about natural remedies. Read: Why we must safeguard our forest muthi.

Call to action

Reflecting on the conference outcomes, Duncan MacFadyen, head of Oppenheimer Generations Conservation and Research, said that amid the stark assessments of the challenges Africa faces, this year’s edition of the conference was “refreshingly positive”.

“It was not just about the ‘world is heating up a rapid pace, our habitats are shrinking, more and more species are becoming endangered, alien invasives are taking over, our waters are polluted’. It was also about what we going to do about it all,” said MacFadyen.

NOW READ: Environmental scientists must network to ward off environmental crises.

- This story was produced with support from Jive Media Africa, the science communication partner to Oppenheimer Generations Research and Conservation.