Mlu Mdletshe, an urban Zulu catches a whiff of Pondo Fever and takes its cultural pulse.

KING Arthur, legend has it, won the British throne by pulling a sword from an anvil. It so happens that South Africa’s Pondo people have a somewhat similar story involving the dethroning of a queen, an essential skill for cooking and a hearty interest in beer.

The story goes the Traditional Council were not happy with the reigning king’s Great Wife, whose eldest son, Phakani, was heir to the throne. The meat she would cook tasted badly and was hard for the councillors’ aged gums to chew on. She also brewed very sour Mqombothi (traditional beer) and was known to be stingy when the councillors visited the royal home.

Mqombothi

On the other hand, one of King Ngqungqushe’s other wives, Mamgcambe, was very generous, could brew the most tasteful Mqombothi and cooked very tender and juicy meat which allowed the elder council members to chew with ease.

So the elders devised a plan to reverse the appointment of the Great Wife. The spear of the nation, Umsila Wengwe, was planted in the ground and Phakani’s mother told to untie the leopard skin wrapping the spear. Mamgcambe was then asked to put back the leopard skin. Having unravelled the leopard skin from the spear, Phakani’s mother was advised that she had removed herself from being the Great Wife and Mamgcambe eldest son, Faku, became heir to the throne, succeeding his father in about 1815.

Faku became the most popular Pondo king, consolidating a number of loosely bound clans into a strong kingdom with an effective military and agriculture-based economy founded on cattle breeding and good grain and maize harvests.

This statue of Mpondo King Faku was made be artist, Xhanti Mpakama. Faku ruled for more than 60 years. He was described as a tall good-looking man, who was courageous, strong and forthright. Photo compliments on National Heritage Monument

Some 250 years later, the spear in the soil incident has faded to legend, but the Pondo’s passion for colourful tales and indeed umqombothi burns bright – something I learnt on a recent hike in their heartland, on the northern Wild Coast, in South Africa’s Eastern Cape province.

It was only one of a string of stories and anecdotes our guide, Sinegugu Zukulu, shared with us as we journeyed by minibus to Ndengane Village, south of the Mkhambathi Nature Reserve, where our 74km hike would begin.

Although Pondoland was assimilated into the former Transkei homeland under apartheid, with Xhosa as the official language, many of its people have kept their culture, traditions and language. Sinegugu is a prime example. A proud Pondo and award-winning conservationist, the 50-year-old taught geography for over a decade, including at a posh boys’ school near Durban, Kearsney College, before chucking it in to develop environmentally-friendly social initiatives on the Wild Coast.

Home stays

These include trails where hikers spend the night in traditional homes, rather than B&Bs or swish hotels. In return for giving the visitors a real taste of Pondo life, the home-stay owners receive a direct slice of tourism pie, in a deeply rural area where there is little formal employment.

Filmaker Gordon Greaves is producing a documentary on the role grassroots home stays play in the rural economy of Pondoland. Photo: Fred Kockott

In a way it reminded me of my family home. I now live in Durban, an industrial city, but grew up in Mabibi, on the shores of Lake Sibiya, in northern Zululand, nearly 700km north of where we were hiking. The lake was our main source of water – the heart of the community. We drank from it, washed clothes on its banks, played and swam in it. It was also where women and girls came to fetch water, so us boys loved going there. It remains one of my favourite places.

Sinegugu and I were soon chatting about the Zulu, Xhosa and Pondo cultures. Many Pondos speak both Zulu and Xhosa, but it’s rarely the other way around, especially for us Zulu speakers. Take for instance, the southern ground hornbill. It’s known as the insingizi in Zulu, and Xhosa as the insikizi in Xhosa. But the Pondos flew off in a different linguistic direction. They call the bird the ingududu, a name few Zulus would know. Curiously, the name is slang in Zulu for “a beer quart”.

The southern ground horn bill, Insingizi in Zulu, Insikizi in Xhosa and Ingududu in Pondo, is an endangered bird in South Africa. Photo: Jan Fleischmann

In Zulu folklore the bird is said to bring rain and killing them is forbidden. But throughout Africa the species is classified as vulnerable by the International Union of Conservation of Nature (IUCN). In South Africa only 1,500 remain, mostly due to loss of nesting trees.

Stopping at Mkhambathi Gorge, we learnt about another important species on the IUCN Red List – the Cape griffon vulture, Inqe in Zulu, Idlanga in Mpondo, and Ixhalanga in Xhosa.

A colony thrives in the Mkambathi reserve, but elsewhere its numbers are declining. Reasons for this include electrocution by power lines, bush invasion, collisions with cars, less available wildlife food, and the demand for vulture parts for traditional medicine. Commercial farmers, too, have killed off raptors by poisoning the carcasses of sheep in a bid to kill predators like jackals.

The Cape Griffon vulture thrives in Mkambathi Nature Reserve but its numbers are declining in many other parts of South Africa. Photo: Hein Waschefort

This lesson from Singugu was a taste of what was to come over the next few days. The man is a walking and talking encyclopaedia, particularly when it comes to plants. With his walking stick and an old sun hat, he reminded me of my late uncle, Sika Ndlovu, who taught me and my brothers all we know about nature. Our uncle often took us on hunting and fishing trips that turned life lessons about the interconnectedness of life.

A stunning, red sunset greeted us on arrival at Ndengane Village. In Pondo this golden hour is known as libantu bahle (when people are beautiful). The home-stay owner, Ma Ntshangase, had prepared a feast of spinach, pumpkin, potato leaves and beef curry to go with pap (stiff maize porridge) and a loaf of bread, cooked over an open fire. One bite took me right back to my grandmother’s kitchen in Mabibi, but also whispered to me: “You’re in Pondoland now.”

Crowing cocks

“Aweh (yes), you will soon catch Pondo Fever,” joked one of my hiking companions, Matt Vend. The troublesome symptom, he said, was that once caught, some never leave the place. After a few years living in the inner city of Durban, I could relate to this.

Also with us on the hike were Natalie dos Santos, a marine biology student; environmental activist, Alice Thompson; a lively group of women from Pretoria, two of them nicknamed Law and Order, and trainee guide, Lonwabo Dlamini. Over five nights we slept in rondavels, on mattresses on the floor, ate more healthy food than I have for ages, washed in basins filled with spring water, woke to the crowing of cocks and set out soon after sunrise.

We crossed rich grasslands full of rare and unusual plants. Although Conservation International lists the area among 25 global hotspots in need of special conservation efforts, Zukulu is concerned that little is being done to protect these floral riches.

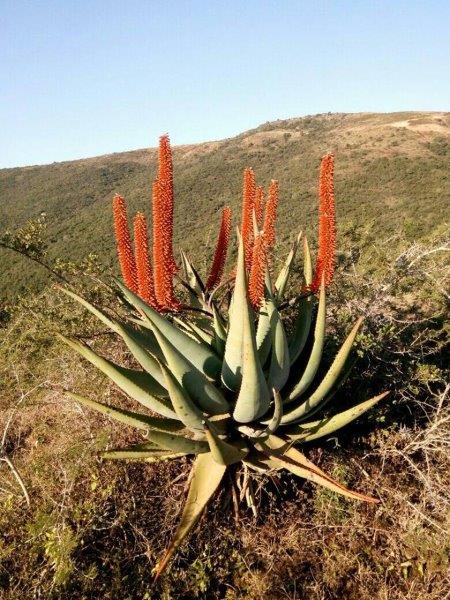

The Aloe forex with its long history of medicinal use is among more than 2200 plants found in abundance within the Pondoland Centre of Endemism on the Wild Coast. Photo Sinegugu Zukulu

I was interested to learn about the medicinal properties of plants such as lemongrass – umqunga in Mpondo and isiqunga in Zulu. It has many traditional uses. Together with its stem and roots, the grass is mixed with water and drank to cleanse the body and immune system – and to ward off bad spirits.

Talking of bad spirits, I got the shivers when Zukulu took us to a deep natural pool where an infamous medicine man, Khotso Sethunsa, is said to have kept a big snake that he used for dark magic. It’s said he brought many people fame and fortune – and today hikers enjoy a dip in the pool – but you will never catch me in those waters.

African viagra

Described as very dark-skinned, fat and rather short, Sethuntsa was a millionaire whose clientele, according to a recent book, included former South African Prime Ministers, Johannes Strijdom (5th) and Hendrik Verwoerd (6th). He had 23 wives and bragged that he could satisfy them all thanks to a herb called Ibangalala. It enjoys a high reputation as an aphrodisiac and is prepared from the powdered roots of certain species of Rhynchosia (snoutbean in English; rankboontjie in Afrikaans). It is said that at 90, Khotso had sired more than 200 children.

Sethuntsa died in 1972, but lives on in history. His big blue and white houses in the Transkei, with the statues of lions at their gates, are now tourist attractions.

The next day our hike drew us closer to the shore, along cliffs overlooking the Indian Ocean. At Waterfall Bluff, Mlambomkhulu River flows off a cliff, directly into the ocean. It’s one of only a few in Africa to do so and it’s a magnificent sight. Some 2km on we reached Cathedral Rock, one of the famous landmarks along the Wild Coast – a majestic clone of Hole-in-the-Wall.

Cathedral Rock got its name from its resemblance to churches in the UK. Photo: Matt Vend

More breath-taking experiences followed over the next three days. At one stage we found ourselves on a precipitous climb, which had Matt leaning his whole body, at a 45 degree angle into the mountain, gripping on to every tiny piece of grass and stable rock so as not to fall.

On our WhatsApp group, Natalie later wrote: “One wrong step for clumsy, height-fearing people like me was sure to send me scrambling to my inevitable death below – at least in my mind. I simply couldn’t take another step. I took so long to move that Lonwabo placed his walking stick between me and my envisaged perilous fall, telling me to hurry up while the old tannies laughed behind me.”

This precipitous climb had hiker Natalie dos Santos trembling in her boots as she turned to take this shot.

This precipitous climb had hiker Natalie dos Santos trembling in her boots as she turned to take this shot.

Earlier I was in awe of the spray of wild crashing waves as they hit a cliff face. But beyond these spectacular scenes and the camaraderie of the hikers, what really made the hike special was the warmth of our hosts who welcomed us into their rustic homes.

In monetary terms, Pondoland’s people are poor, just as they are in Mabibi, where I come from. But they live simple, healthy lives. Unlike in the cities, they share what they have. In my family many have left Mabibi over the years to work in the cities to make money, returning years later, ill and dying. I heard similar stories in Pondoland.

As it happened, our hike drew to a close on a Friday – almost everywhere worldwide a time to celebrate. There are no pubs in deep rural Pondoland, but we did pass a homestead where a white flag had been raised on a long pole to let the village know beer was being brewed.

Unfortunately, it was a little early so we never got a taste, but I am sure those elders from King Faku’s childhood days day would have approved of the mqombothi about to be generously shared.

- Mlu Mdletshe is a Durban University of Technology journalism graduate enrolled on Roving Reporters environmental journalism training programme supported by the Human Elephant Foundation. His Wild Coast hike was sponsored by the 8 Mile Club, compliments of the Wild Swim expedition which raised funds for marine conservation and eco-tourism on the Wild Coast.