How we consume seafood has become an implicitly political act. Our choices are our votes, defining our relationships to the ocean. It’s no longer enough to be motivated by half-price sushi. We need to work harder to know where our seafood comes from and whether or not eating that species can be considered viable.

Opinionista: Christopher DZ Mason

First published in Daily Maverick

South Africa’s inaugural Marine Protected Areas Day was on 1 August – a celebration of the 5% of our waters that are protected as sanctuaries for marine life, and a stark reminder that the other 95% of the oceans are not.

The country’s low-slung and gleaming coastline is one of its greatest treasures. It boasts 2,800km of wildly diverse shoreline with waters that support more than 2,000 fish species across more than 150 ecoregions. Add to this South Africa’s exclusive economic zone, which covers a whopping 1.1 million square kilometres, and it completes a picture of truly vast ocean resources.

Zoomed-in

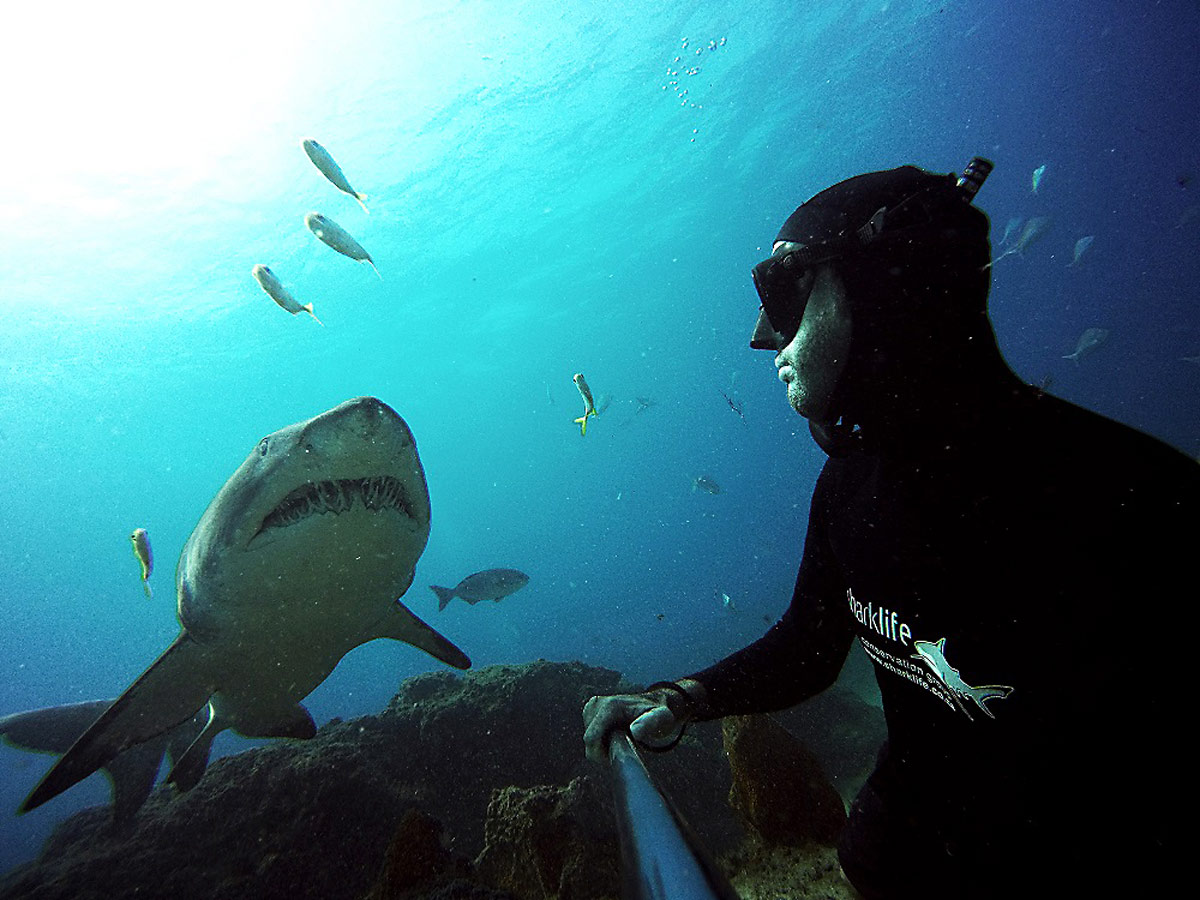

The scale makes it easy to lose sight of how the health of a single beach or reef can affect the whole system, or why small pockets of marine protected areas are so important. For this, one needs a zoomed-in view, which is something I’ve been afforded while spearfishing and free-diving along our coast. I’ve seen first-hand the difference that marine protected areas make to the way ocean ecosystems look and feel; how protected areas hold populations of big, mature fish while next door in legal fishing areas these species are far smaller and less abundant.

I’ve come to understand that marine protected areas give us a sense of what the baseline health of an ecosystem should look like, and I’ve also had to confront the difficult moral and ethical questions raised by my contribution to the denuding of these places. All of this has led me to believe that we have come to a point where we need to re-evaluate how we perceive ocean wilderness and consume the animals that come from it.

What’s also clear to me is that how we consume seafood has become an implicitly political act. Our choices are our votes, defining our relationships to the ocean in direct or indirect terms. It’s no longer enough to be motivated by half-price sushi. We need to work harder to know where our seafood comes from – not just the rough area, but the actual environment in which it was found, how it was caught, and whether eating that species can be considered viable.

Luxury

For some people the answer is “don’t eat fish”. For me, the way forward is only eating what I catch. Of course, this is not possible for most. There are billions of people worldwide who rely on the oceans for food and jobs, who are often in poor coastal communities and don’t have the luxury of choice.

What we all share, however, is the opportunity for growing our relationship with the ocean through active interest and care. It brought me great joy to catch the first fish my daughter ate. She saw the whole animal first, a sleek and handsome yellowtail, and watched as I filleted and cooked it, understanding what it was she was eating when she took the first bite. It was the beginning of her relationship with a fish that had become for a time each summer our primary source of protein. What one feeds one’s family is an intimate and important thing. We’re each allowed to make that choice according to our beliefs and preferences, but regardless of what we choose – soy burgers, fresh fish or beef steaks – our choices have repercussions.

Relationship

The deeper I pursued a direct relationship with the marine animals we ate, the more I began to see that the fish I was hunting, and the oceans in which they lived, were under far greater stress than I had first understood. For while the fast-growing and seasonally abundant pelagic species like Cape yellowtail proved to be exciting and sustainable green-listed quarry, the large reef fish of the Cape are already in great peril. Their life histories – being long-lived, slow growing and hyperterritorial – make them far more susceptible to fishing pressure.

One species that seemed to define the modern plight of the Cape reef fish with vivid and alarming complexity was the Red Roman. Striking and proud in bearing, it is one of the last of the large reef fish to still be seen with some regularity in the great African kelp forests of the Cape.

Docks

Traditionally, Red Romans have been highly sought after by line and spearfishermen alike. I remember going as a kid to the East London harbour with my Yiayia (Greek grandmother), who loved nothing more than an early trip to the docks to meet the fishermen on their return, and who prized Red Roman as an eating fish above all others.

These days the Red Roman is listed as near threatened on the IUCN Red List for Threatened Species and a quick Google search shows it’s still easy to buy them from, for example, Fish 4 Africa. It’s also legal for recreational fishermen to catch up to two a day with the correct permit.

Plight

But knowing this does not tell the whole story of the Red Roman or its importance as an indicator species in reef systems. Diving along the coast of False Bay, I would sometimes see Red Romans adding their custom splash of colour to the seabed. But they were few and far between compared with the numbers I saw in the “no-take” safe zones of the bay’s marine protected areas. When I started asking fishing friends about whether they thought we should be catching Red Romans, there was a mix of replies, ranging from “we recreational fisherman don’t make nearly as much of an impact as commercial fishermen” (which is true, with the disclaimer that recreational fisherman still make an impact), to “if it’s big and red, don’t shoot it!”

The latter came from Steve Benjamin, a good friend who taught me how to dive. Steve is both a marine biologist and a spearfisher and consciously walks the line that connects the two. It was from him that I started learning about the various fish species we encountered, and which ones I could target. Steve chooses to point his camera rather than his speargun at Red Roman, and has taken some of the most beautiful photos of the species in circulation today, and it was after talking to him about the plight of the Red Roman that I began to realise that it was perhaps because of it’s crimson conspicuousness that the species was so important. It was the last big red fish we were seeing on the reefs; the final warning light in a long line of now missing keystone species.

Context

To understand what all this meant, I turned to another friend who was qualified to give me a real answer – filmmaker and conservation journalist Philippa Ehrlich. Philippa was writing about the urgent need to protect South African reef fish back in 2015 and it was her article that had helped me see the Red Roman in the context of an embattled line fishery. When I asked Philippa about the condition of the reef fish of False Bay now, she started with a story:

“A friend of mine, Lauren de Vos from Save Our Seas Foundation, had been telling me for a long time about these incredible reef fish species that live in South Africa and False Bay. But, I have dived in False Bay for most of my adult life and when I went through her list of fish I realised pretty quickly that the only one I was seeing was the Red Roman. So much of the original diversity had disappeared, which included animals like Red Steenbras, Red Stumpnose, Knifejaw, Jan Bruins, White Steenbras, Galjoen and Musselcracker. What was so shocking was that these were animals that have been gone for a long time. It’s not like they’ve only been fished out in the past 20 to 30 years.”

Havens

Indeed, the damage started many decades before, probably when large-scale commercial fishing became popular in the 1950s. By the turn of the century it was already clear to those looking at the data that we had a big problem with our reef fish (also known as linefish) populations. The 2013 edition of the Southern African Marine Linefish Species Profile puts it in plain English: “Following the declaration of an emergency in the South African linefishery in December 2000 and the recognition of the urgent need to rebuild many overexploited linefish stocks, implementation of the species-specific management plans eventually took place during the mid-2000s.”

It’s now clear that those management plans were not good enough and that there is a dire need for more marine protected areas, which act as havens that give fish populations the time and safety to recover. And, despite my despair in having to write this sentence of pure gloom, it’s only getting worse. The WWF Sassi website tells us there has been a dramatic increase in the number of fish taken out of the seas in recent decades, with many linefish species in South Africa being either dangerously overexploited or completely collapsed.

Approach

While our approach to harvesting marine life clearly needs careful overhauling, perhaps another part of the problem lies in the language we use to talk about “sea” food. When we think of “stocks” the word connotes a “quantity of something” that can be controlled and may fluctuate up or down. Like livestock, bred commercially, or commodities like whisky, wheat or chocolate, of which one can purchase more when “stocks” run low. Not so for the oceans and the fish in them.

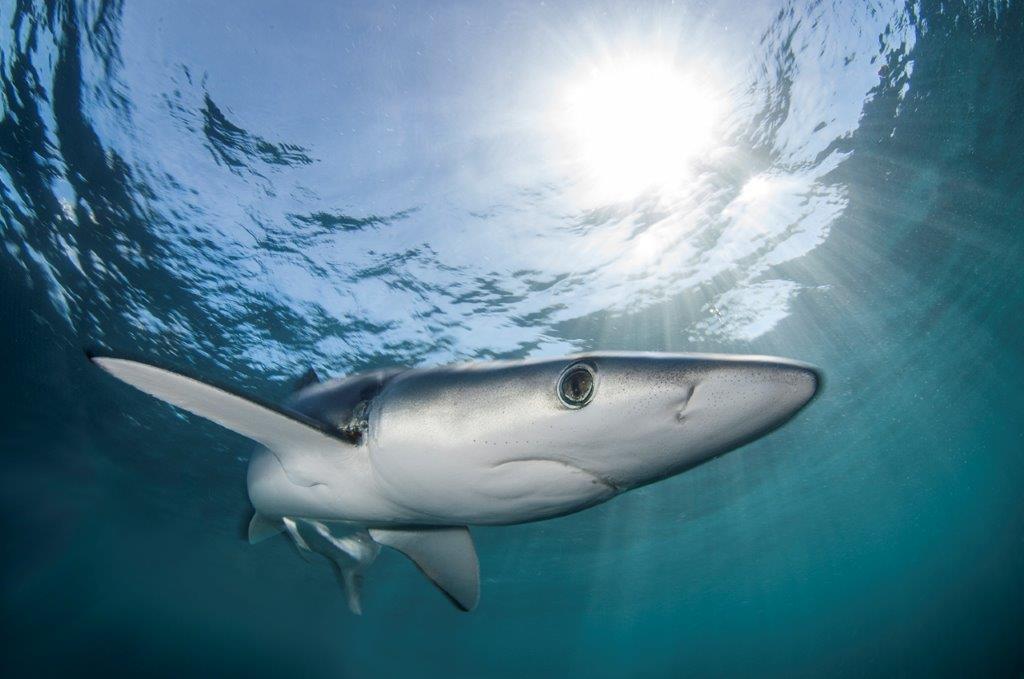

We tend to forget that these are wild animals which we track and capture with ever-increasing technological sophistication in industrial fishing industries. Recreational fishing numbers are also growing, as is our skill in catching fish. When considering terrestrial and marine wilderness areas side by side, the only justifiable method of conservation is then complete protection for marine life within “no-take” sanctuary zones, like we do on land.

Treasure

If we start thinking about them in the same light as our iconic game reserves, the conversation shifts. What makes a leopard’s life of greater value than a predatory reef fish like a Red Steenbras? The fish can live for up to 55 years, whereas the cat would typically only last 12, but yet the former seems doomed by its own deliciousness.

When asked about the importance of marine protected areas, Steve Benjamin replies in emphatic terms: “The oceans are under a massive amount of pressure, from fishing and industry, and they never get a break. Marine protected areas are like oases in a desert of human disturbance. We really need to treasure these last locations where ecosystems can remain functional and fish can live out their lives in a normal way.”

The idea of a fish living its life in a “normal” way stuck with me. The implication is that for the most part fish continually have their lives affected by humans, through fishing, pollution or habitat destruction. Thinking of fish as animals with a sovereign right to their own full experience of life is not something we’re used to.

Habitat

But anyone who has seen the Oscar-winning documentary My Octopus Teacher is forced to re-evaluate the narrow and reductive “non-human” viewfinder we’ve been using to look at fish and marine invertebrates. It was Philippa Ehrlich, a co-director of the film, who drew me towards the idea of fish living a full life. It’s a theory that is borne out with every new hour I spend observing the underwater wilderness just past the shore.

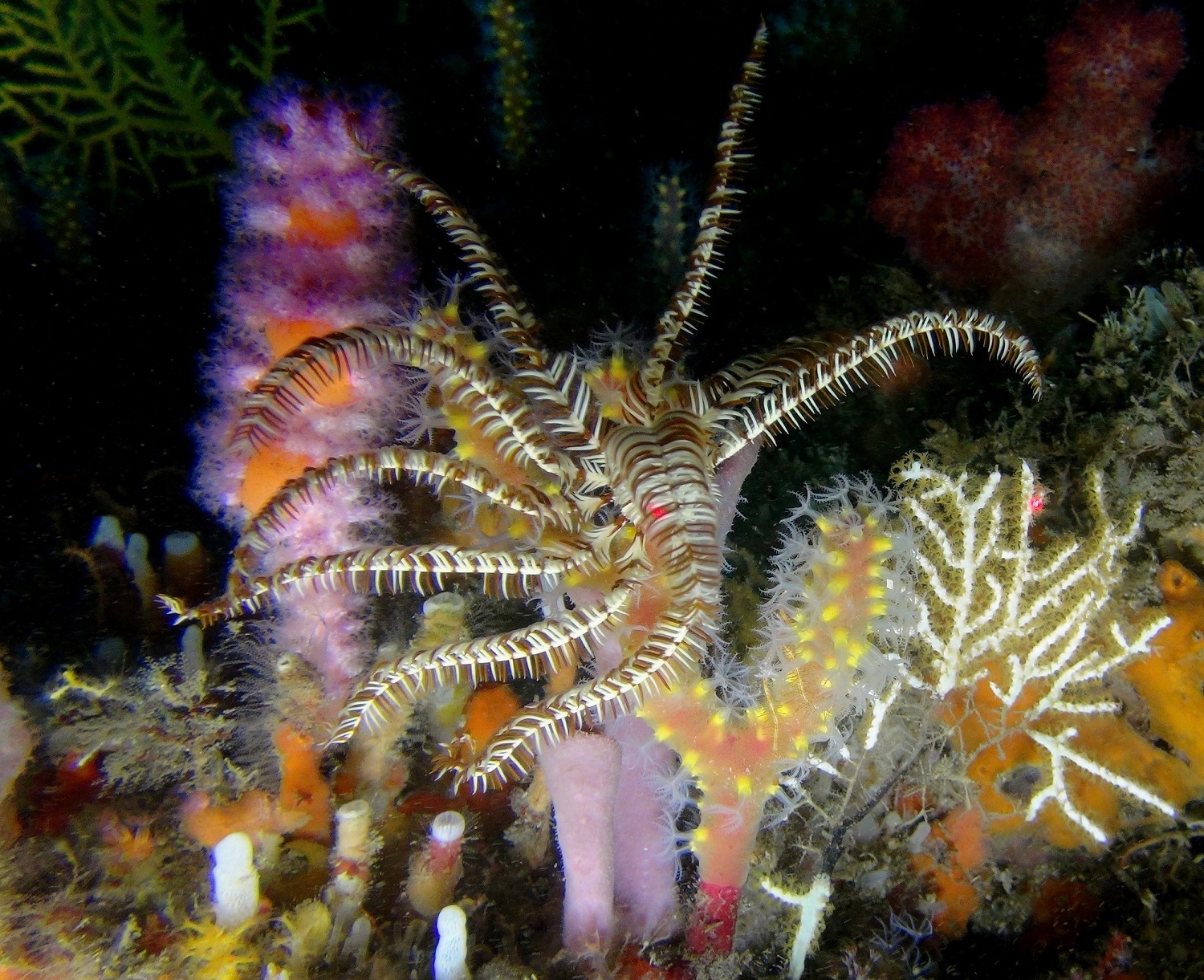

About the return of the larger reef fish of the Cape, Philippa was confident: “Here we have this incredibly intact habitat, in the great African kelp forest, which as far as kelp forests go is one of the healthiest in the world, and it’s just waiting to be repopulated with an abundance of reef fish that lived here 100 years ago. We can already see they’re coming back inside our marine protected areas, but they need all the help they can get. They’re fragile and their life histories are complex, and they’ve been pushed to the brink.”

It’s because of all of this that I choose to celebrate Marine Protected Areas Day, which helps raise awareness about the value of our marine ecosystems and the desperate need for us to do more to protect them. Marine protected areas are important for so many reasons, such as providing resilience against climate change, nurturing species previously thought to be extinct, and creating important economic benefits.

Protection

But for me, they’re also vital because they allow us to see the way our oceans should look, bringing us into a state of reverence for these aquatic wildernesses and their quiet mystery. Seeing places like these gives us something to strive for. And 5% is not enough. According to the IUCN and Australian Marine Sciences Association we should aim to give 30% of our waters full sanctuary protection if we are to staunch the loss of life inflicted by our current practices.

Months after I spoke to Philippa about reef fish, she sent me some pictures – vibrant images of Red Steenbras, Knifejaw and Red Roman swimming through shimmering kelp forests. She told me she’d found a tiny patch of hard-to-access kelp in the heart of a marine protected area no-take zone where these species were swimming. They were all juveniles, the first ambassadors of their kind to return to their ancestral waters.

I really want to be alive in a world where these fish grow to become giants. A world where it is us fishers who are restricted to small patches, while the rightful owners of the oceans can swim freely through cool, clean waters.

-

- Christopher DZ Mason is a wildlife filmmaker and writer who has produced more than 20 natural history documentaries for international broadcast, and writes about environmental concerns.

FEATURED IMAGE