A world without trees would be hell on earth

As a massive indigenous tree planting project takes root in South Africa, FRED KOCKOTT and JANE ROSS reflect on the relevance of a poignant tree planting tale from French author, Jean Giono.

People can be as effective as God in realms other than destruction, wrote renowned French author, Jean Giono, in an allegorical tale about a man who planted trees. For more than three decades between the First and Second World Wars, Elzéard Bouffier planted seedlings every day. He singlehandedly transformed barren landscapes of the Alps into a veritable Eden.

“Creation seemed to come about in a sort of chain reaction,” wrote Giono. “The wind, too, scattered seeds. As the water reappeared, so reappeared willows, rushes, meadows, gardens, flowers, and a certain purpose in being alive . . . Everything was changed. Even the air.”

Published in 1953, Giono’s tale has deep relevance in today’s world of climate change, particularly for people who have forgotten – or never been aware of – the restorative powers of trees.

It is this restorative power that drives the vision behind a massive indigenous tree planting project taking root in South Africa: Greening your Future.

Over the next year, the project will see over half a million indigenous trees re-planted in their natural habitats surrounding game parks, rural communities and urban green corridors in KwaZulu-Natal – from Durban through to Tembe Elephant Park on the Mozambican border – and in several communities in Gauteng, Mpumalanga and the Western Cape. Spearheaded by the environmental NPO, Wildlands, and the Natural Resource Management programme of the Department of Environmental Affairs (DEA), the project sets out to show that meaningful livelihood opportunities can be created through restoring natural eco-systems and improving bidodiversity.

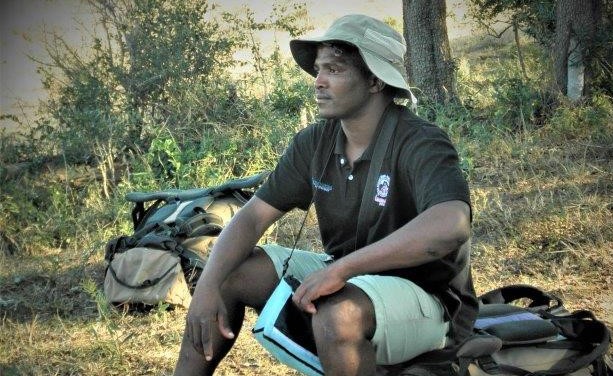

Championing the project are two ecologists, Zoe Brocklehurst and Andrew Whitley, who attended this week’s World Conference on Ecological Restoration in Brazil to promote Greening your Future work.

“We want to develop a restoration protocol for South Africa that incorporates scientific and internationally approved evaluation and monitoring mechanisms to assess the value and success of projects like this,” said Whitley.

It was 12 years ago that Wildlands started the Trees for Life programme, spawning a generation of Tree-preneurs – growers of indigenous trees. Once the small trees reach heights of around 30 cm, they are bartered for bicycles, school uniforms, food hampers, building materials, agricultural supplies, school and university fees. The project now sees over 3,500 Tree-preneurs grow over 300,000 trees every year. The young trees– more than 30 different indigenous species – get transplanted in various communities to create green corridors – the final Greening your Future phase of the project.

“In terms of degradation of the planet, people are now realising that unless we start restoring what we have destroyed, it will not be sufficient to sustain life, and most importantly will not secure sufficient water supply,” said Brocklehurst. “That’s what our programme is all about: the bigger picture – repairing the health of the ecosystem so that it functions better, improves biodiversity and brings benefits to people.”

For Brocklehurst, the socio-ecological aspect of this work stimulates her the most.

“It’s wonderful seeing people recognise the value of natural eco-systems,” said Brocklehurst. “For some, it’s a lightbulb moment. In others, a gradual change in understanding.”

She said in deep rural areas, people did not need much convincing, particularly when it came to clearing alien species.

“There are elders who remember what ecosystems were like before alien plants took over. So many times, I’ve heard an ol’ kehla say: ‘Hawu, I used to come down here and fetch buckets of water. Now it’s dry – the whole year’.”

With Arbor Week upon us (September 1 – 7), Brocklehurst and Whitley are hoping that people, particularly parents and teachers at schools, will help educate children about the importance of trees.

Trees clean the air, filter out pollutant gases, dust and particulates, said Brocklehurst. They cool our streets, cities and villages, prevent erosion, provide food and essential shade which saves water, the scarcity of which now impacts on life throughout Africa.

Tree leaves also reduce rainfall runoff, allowing water to flow down tree trunks into the earth below where it gets filtered and cleaned by the soil. And, yes, trees breathe too, sucking out carbon dioxide from the air and producing life-giving oxygen in return. In one year, an acre of medium-sized trees can absorb up to 2,6 tonnes of carbon dioxide (CO2) – the equivalent amount of CO2 emitted in exhaust fumes when a person drives a car for 41,000 kilometres. The build-up of CO2 in the atmosphere is one of the major causes of climate change.

It is thus no surprise that amid predictions of climate change wreaking unprecedented havoc and disaster for generations to come, trees have become the front-line warriors against global warming.

And as many studies – and Giono’s 1953 tale – reveal, the restorative power of trees can also heal the human spirit, reducing violence and fear that is often so prevalent in poverty-stricken, barren lands.

In describing the desolation of the treeless landscapes, Giono wrote: “All about me was the same dryness, the same coarse grasses . . . The wind blew with unendurable ferocity. It growled over carcasses of the houses . . . The soundest characters broke.”

If Giono were alive today, Wildlands’ Greening your Future project would undoubtedly make him smile.

“It’s become so much more than a venture aimed at planting indigenous tress. It’s now a high-impact cross-synergy project which is enabling community upliftment and helping people realise their dreams,” said Wildlands’ Marketing Deputy Director, Lauren van Nijkerk.

Following the publication of The Man Who Planted Trees, most readers believed that his softly-spoken, humble hero, Elzéard Bouffier was a real person; that Giono’s tale was autobiographical.

Not so, Giono later wrote in a letter to a French official. He was a fictional person, said Giono whose goal in writing the story was simply to promote the planting of trees. “This seems to have been attained through this imaginary person. It is one of my works of which I am most proud.”

Within three years of publication, The Man Who Planted Trees, had been translated in Danish, Finnish, Swedish, Norwegian, English, German, Russian, Czechoslovakian, Hungarian, Spanish, Italian, Yiddish and Polish. Giono gave rights for the work to be freely distributed. It is still used today as an education resource worldwide.

As in Giono’s allegory, in which the colossal Linden tree symbolises rebirth, in celebrating Arbor Week this year, South Africa has its own unique symbol. Our 2017 Tree of the Year is the Buffalo Thorn, a hardy species that embodies resilience – courage and perseverance against all odds – the very qualities needed at this critical juncture of our planetary heritage. We need to clean up our act.

Projects like Greening your Future and associated Arbor Week activities are a step towards this: creating a healthy environment and a conscious culture that will sustain life for future generations.

This feature story was commissioned by Wildlands and was also published by in the Sunday Tribune. Click here to view pdf of published story.