The rehabilitation and release of three poisoned vultures is celebrated as threats to the species’ survival escalate, writes Will Western

One swallow doesn’t make a summer, but the release of three critically endangered vultures really is reason to cheer, say conservationists.

The African white-backed vultures had been nursed back to health after eating from a poisoned carcass set for them, experts believe, by muthi traders.

It was one of four separate poisoning incidents in Zululand last year, said Chris Kelly, Wildlife ACT director for species conservation. Kelly is among many conservationists concerned that deliberate poisoning of vultures for belief-based use is on the increase.

The three released birds were poisoned in an incident that left a total of five survivors and 56 dead.

According to records kept by the Endangered Wildlife Trust, more than 1,200 vultures were deliberately poisoned in Southern and Eastern Africa last year. Culprits include poachers who poison the carcasses of elephant and other game in an apparent effort to conceal illegal activities from rangers. These poisonings are referred to as “sentinel poisonings”, as vultures circling over poached animals alert rangers to the killings.

Homecoming

On a recent bright winter morning, the three rehabilitated African white-backed vultures made a homecoming, taking to the skies above Zululand hills, near uMkuze.

Ben Hoffman, of Raptor Rescue who treated the birds when they were rescued nine months ago, explained the significance.

“A vulture takes between five to seven years to reach maturity, and they lay one egg a year. That’s two birds that need two years and a 100% success rate just to replace themselves.”

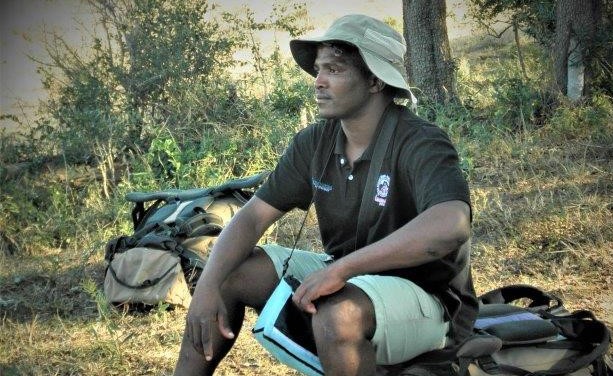

Helping improve the odds are the men and women of the Zululand Vulture Project, which draws together Ezemvelo KZN Wildlife, Raptor Rescue and Wildlife ACT.

Swift action

“Swift response is everything”, said Kelly.

“Five survivors and 56 deaths doesn’t sound that great, but by responding rapidly, hundreds more birds were prevented from feeding, and by removing the poisoned carcasses and decontaminating the scene, hundreds more again were saved – as well as other species of scavenger.”

Wildlife ACT took the rescued birds to Raptor Rescue in Camperdown, near Pietermaritzburg, where Hoffman, a raptor rehabilitation specialist, and his team set to work.

They flushed the birds’ crops and gave them activated charcoal to absorb toxins.

Atropine, a medicine used to treat certain types of nerve agent and pesticide poisoning, was administered.

Fattened up

The birds were fattened up and then allowed to get thin again, to use up their toxin-storing fat reserves.

Before releasing the rehabilitated birds in the Manyoni private game reserve, the Zululand Vulture Project team fitted them with GPS trackers.

These will help conservationists better understand the vultures’ feeding and roosting habits.

It should also give them an insight into the landscapes they prefer – and to see if the birds survive.

The team chose Manyoni because it gave the birds a better shot at safety after release. It was also in the heart of an area in northern Zululand that has suffered a 75% crash in nesting vulture pairs since 2010.

The area includes uMkhuze, Pongola, and Magudu.

No 1 threat

Kelly said poisoning was the number one threat to vultures in KwaZulu-Natal and all six of South Africa’s true vulture species were at risk.

There were other threats facing the country’s vultures too.

“Collisions and electrocutions with power-lines and pylons. And habitat change and reduction all take a big toll,” he said.

The continent’s vultures are now in rapid decline, with most species at risk of extinction.

Rapid decline

The International Union for Conservation of Nature Red List of Threatened Species in 2017 classed 39% of vulture species as critically endangered.

The Zululand Vulture Project focuses on three nesting species: the white-headed vulture (Trigonoceps occipitalis); African white-backed vulture (Gyps africanus); and lappet-faced vulture (Torgos tracheliotos).

The white-headed and white-backed vultures are listed as critically endangered; the lappet-faced vulture is endangered.

Wildlife ACT runs rural community conservation projects and education programmes to teach people about the importance of vultures to the environment. – Additional reporting Fred Kockott and Matthew Hattingh

- This story forms part of Roving Reporters Thin Green Line series.

How the Sunday Tribune covered the story

Click here or on image below to download the pdf