It was a bizarre and disturbing sight. About 100 sharks – beheaded, finned and gutted – dumped on Strandfontein beach along the False Bay coast. Why were they there? What was their intended destination before being illegally abandoned? Who was responsible? asks Donn Pinnock of the Conservation Action Trust

First published by Daily Maverick

The pile of dismembered bodies were mostly soupfin sharks. Word has it they were from either Gansbaai or Struisbaai, destined for a fish processing plant in Cape Town but had gone off and dumped. A problem of stage six loadshedding, perhaps. But was there a bigger backstory?

Soupfin sharks dumped on False Bay’s Strandfontein Beach. (Photo: Chris Fallows)

The search for answers would lead from demersal shark longliners, line fishermen and trawlers, by way of the Department of Environment, Fisheries and Forestry (DEFF), to the danger of eating fish and chips in Australia. It would also suggest, in part, reasons for the recent decline in the number of great white sharks and the current crisis in the lucrative shark-cage diving industry.

Line fishing

The source of the dumped sharks was probably line fishing boats, but the main shark fishing boats are the demersal shark longliners Mary Anne, White Rose and Suriam, which fish close to shore, are based in Port Elizabeth and which supply companies like Fisherman’s Fresh in their home port and probably Viking in Mossel Bay. They’re licensed by DEFF to catch sharks and there’s no upper catch limit, nor any body size limit.

These three boats zone in on smooth-hound and soupfin populations and focus their activities around marine protected areas (and occasionally in them) and pull out upwards of 30 000 of these sharks a year. DEFF has recommended slot limits (no catching younger or more mature animals) since at least 2007, and again in 2011, 2015 and 2017, but DEFF is ‘waiting for approval’ for this to be implemented.

DEFF scientific research, which is world class, has shown that the maximum sustainable upper limit should be set at 75 tonnes annually. However, this would make the industry less profitable so it hasn’t been implemented. The Department estimates that over the past 10 years annual catches of suoupfin alone has fluctuated between 146 and 472 tonnes. The result is that populations have crashed.

Little monitoring

There are no fisheries observers on the boats and catches are only occasionally checked and mostly rely on commercial logbook data to track catches. Sharks are also caught as bycatch in other fisheries, so the final catch weight or composition is anybody’s guess.

A great white shark illegally caught on a longline fishing boat and secretly photographed.

The Department managers knew these sharks were racing towards major problems. They also openly acknowledged that even if all fishing for these species stopped, the soupfin stocks would only bounce back by 2070. Yet they allowed the fishery to keep plundering at up to four times the level necessary to avert local species collapse. According to DEFF scientists, this is presently totally unsustainable.

But let’s start at the other end. Until recently, the fish you ate with your chips in Australia was predominantly snapper, the country’s favourite recreational and commercial fish. This was massively over-fished and last year the government banned catches in a number of key waters until 2023 (angering many fishermen) and imposed stiff fines for transgressions.

Maybe sharks could fill the gap? However, in 1991 the Australian smooth hound shark industry had collapsed and they were being imported from New Zealand. Then that fishery became oversubscribed and the demand shifted to South Africa, an area which they must have known had poor shark management or legal compliance. They’d found the perfect suplier.

Maybe sharks could fill the gap? However, in 1991 the Australian smooth hound shark industry had collapsed and they were being imported from New Zealand. Then that fishery became oversubscribed and the demand shifted to South Africa, an area which they must have known had poor shark management or legal compliance. They’d found the perfect suplier.

That was good news for local shark fishers. According to Dr Enrico Gennari of the Oceans Research Institute, the smooth hound catch numbers were 17 558 sharks in 2016, 18 298 in 2017 and 30 112 in 2018 (the 2018 numbers convert to around 210 tonnes). ‘Fishing at current mortality rates, a decline in harvestable stock is certain,’ he said. ‘I’m quite sure right now this species would be in the endangered category.’

Chemicals

But there’s a further problem the Australians may not know about and will be unhappy to discover. South African waters are far from pristine, with toxic runoff from factories and farms entering coastal waters. Local sharks are apex predators and, as bioaccumulators, they retain heavy metals like mercury and arsenic (eat a mako stark steak at your peril).

They take in high levels of these human-produced chemicals and heavy metals from both skin absorption and from consuming their prey. These dangerous chemicals and metals add up over time and quickly reach levels dangerous to humans. They can cause various neurological dieseases such as dementia.

According to a South African research report on shark meat, mercury readily vaporizes and may stay in the atmosphere for up to a year. It ultimately accumulates in lake and sea sediments where it’s transformed into toxic methyl mercury, accumulating in fish tissue, especially those at the top of the aquatic food-chain. By this means, it enters the human diet.

Arsenic is used in the production of pesticides, treated wood products, herbicides and insecticides and generally enters coastal waters through river runoff.

Research by Adina Bosch and others in Langebaan Lagoon found that one in three smooth hound sharks analysed in 2015 had methylmercury and arsenic levels WAY above allowable limits and contained 14 other heavy metals.

Exported

DEFF scientists have no idea whether sharks exported to Australia are tested for heavy metals and are not sure who should be doing this or at what stage in the commercial process. It’s certainly not being done by DEFF. When I asked Fisherman’s Fresh, which exports sharks to Australia, what checks they do for heavy metals in their exports, director Marius van Heerden refused to talk to me. The National Regulator for Compulsory Specifications says it tests sharks for mercury but refused to provide any proof or statistics?

Taken together, this means there’s a strong possibility that South Africa is exporting potentially hazardous shark meat that ends up in Australian fish and chips.

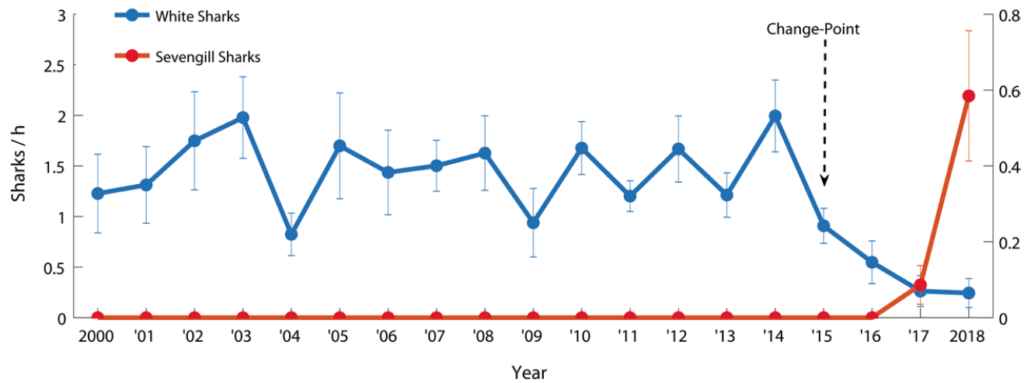

But there’s also another problem. Great white sharks are disappearing from local waters. According to naturalist Chris Fallows of Apex Shark Expeditions who has worked with great whites in South Africa for over 30 years, ‘in the past few years there has been a calamitous crash of our great white populations along the Cape south and southwest coastline.’ In the past three years the False Bay Sharkspotter programme has seen counts go down to almost zero.

This was initially attributed to the presence of two orcas, Port and Starboard, which have been seen in False Bay at least a dozen times. According to Fallows, however, ‘our data shows them to have been present on many occasions since at least 2015 – at least five other pods have been in the bay since 2009.

Migration causes

‘At no time did we ever notice a decrease in white shark numbers when they were in the bay. I’m not saying they don’t have an effect, but the the orca effect lasts maybe 4–8 weeks, not years.’ Are they migrating eastwards because of climate change is relocating food supply, are more orcas migrating north from the Southern Atlantic and scaring whites or is is something else?

According to Fallows the main cause is over-fishing. He says small sharks and not seals are the primary food source of great whites. DEFF says there’s no solid science to back this claim. But Fallows and Enrico Gennari say it’s based on many decades of local knowledge from cage dive operators and fishers as well as research done on great white stomach contents done by the Natal Sharks Board.

In the world’s largest study on great white diet, it was found that smaller shark species formed the most important food component in over 590 dead great whites analyzed.

‘Seals represent a seasonal component in the great whites diet,’ says Fallows, ‘but for more than half the year their food is mainly smooth hound and soupfin sharks, which used to appear in False Bay in great numbers. When the great whites were not at seal island we looked for them where the smooth hound sharks were known to aggregate.’

‘Then, in the late 1990’s DEFF gave out demersal shark longline permits and line fishing for sharks in the bay was suddenly on the increase. By the mid to late 2000’s we noticed a slow decline of white shark sightings at Seal Island, nothing drastic but an overall down trend.

‘Suddenly around 2015 three boats started fishing the resource hard. They learnt how, where and when to target the smooth hound and soupfin sharks. Their technique was highly focused and localised to sites where these species gather.

Double whammy

‘Their catches soared and our sightings of white shark in False Bay went through the floor. In a nutshell there are no longer enough smooth hounds and soupfins left in False Bay to sustain the white sharks for the eight months of the year they’re not at Seal Island.

‘Add to this the octopus fishery which started in earnest around the same time targeting the key food source of smaller sharks and you have a double whammy.’

According to Fallows, DEFF did not do an impact study (EIA) to determine what the effects of the removal of these smaller sharks would have on the greater ecosystem. Why not – that’s their job? Here’s a possible reason.

In the past 10 years, DEFF has lost around 80% of its fish scientists who were, and still are, among the best in the world. They now simply don’t have the human resources to cope with a complex and rapidly evolving climate and other enironmental issues and, furthermore, DEFF management often simply ignores their advice.

Policies are often just cut-and-paste from elsewhere and not based on targeted local science on specific species. It’s all bad news for fish, fishers – and tourism.

‘In order to sustain a fishery that’s causing ecological collapses, wiping out apex predators and contributing a miniscule amount to GDP, food security and job creation,’ says Fallows, we’re killing one of the Western Cape’s prime tourist attractions and the source of thousands of jobs.

Tragic

What’s is also tragic is that coastal fishing communities that have relied for many decades on species now being caught as target species or bycatch by the demersal shark longline industry no longer have a viable income in the areas where these boats ply their trade.

‘All this to supply Australians with fish and chips, while they cleverly manage and conserve their own resources.’

The local solution to the fish and chips problem Down Under could turn out to be a Faustian bargain. Given the heavy metals in these sharks, we could be slow-poisoning many Australians.

The flavor of the day seems to be short term gain that makes no sense in terms of the environment, human health or sustainable income.

Banner image courtesy of Conservation Action Trust