An online platform is making it greener, cheaper and easier to support conservation agencies worldwide. The way it works can take some effort to get your head around, but it’s intended to appeal to digital natives, cryptocurrency fans and traders. Rio Button speaks to its founder.

A close encounter with wildlife can really stay with you, changing perspectives and nudging career choices in novel directions. Just ask computer scientist and entrepreneur Jason Smythe who has established an award-winning online platform that uses blockchain technology to take some of the schlep out of fundraising for conservation agencies.

It was a decade ago, but Smythe remembers the moment well: “A stare-down with a lioness in the still of the night during my shift on watch; standing there with only a small flashlight in my hand and a small fire in front of my feet, I was frozen stiff.” He was 17 at the time and on watch while friends slept. They were camping under the stars, deep in the Hluhluwe-Imfolozi Park, Africa’s oldest nature reserve.

Fast forward a few years to 2018 and Smythe was again up late, around 3am on a Saturday. A software and blockchain engineer, he was at the EthCapeTown hackathon, a weekend-long marathon during which computer programmers compete and collaborate to develop products. It’s a team sport for geeks and he was there with four friends from his varsity days.

Late night adventures

But things were going badly for the lads, all University of Cape Town computer science honours graduates. They were on their laptops frantically searching for ideas or brainstorming, but couldn’t agree on what to build. They decided to grab some sleep, only to awake in a blur a few hours later. Saturday morning sped by as they scrambled to create code for a number of fleeting project ideas. Still nothing clicked and by the afternoon they decided to scrap everything and start from scratch.

Finally, they settled on an idea. It married conservation fundraising and non-fungible tokens (NFTs) – digital assets that represent items such as photos, videos, audio, and other types of digital files. These are stored on a blockchain, a digital ledger that certifies the asset is unique and who owns it. The idea would later develop into Wildcards, an online platform that lets cryptocurrency and NFT investors support conservation agencies by picking from a variety of Wildcards.

By purchasing a wild animal NFT they become its guardian and contribute to the animal’s conservation through donations until someone outbids them for the card. The platform makes it appealing and easy for crypo-currency investors and people familiar with blockchain to support conservation. And it lets them exhibit their contributions, as their cards can be displayed in internet galleries and on social networks. And conservation agencies benefit from regular funding from a previously untapped and growing network.

Globetrotters

Smythe and his mates Jonjon Clark, Denham Preen, Sean Markham and Şen Ferhat won the EthCapeTown hackathon with their working proof of concept Wildcards platform. On a roll and in the grip of wanderlust, the tech nerds went on to win the ETHTurin hackathon in Turin, Italy, and to attend a circuit of geek events worldwide, including the Ubisoft entrepreneurs lab in Paris, France, and CV Labs start-up incubation programme in Zug, Switzerland.

It all helped them to improve the platform, making it more accessible and user friendly. Along the way, Wildcards also gathered a global audience which later grew into a user base. It attracted funding which helped to start and sustain the platform while it grew and developed its own revenue streams.

Wildcards identified grassroots conservation agencies around the world that were working to save wildlife on the ground and invited them to apply for help with fundraising. Getting donations to support their work is often the biggest headache agencies face so many were keen to join the platform, which launched cards to raise funds for the particular animals they conserve.

Agencies benefiting from the platform now include BioS, which conserves Peru’s Pampas cats; MareCet, which advocates for marine mammals in Malaysia, where most of the population don’t know these creatures exist in their countries waters; and Tsavo Trust, which protects Kenya’s super-tuskers — elephants whose tusks are so long they scrape the ground.

Breaking barriers

“The intersection of economics, community, and altruism that the Wildcards platform enables, is contributing to breaking down the traditional barriers to conservation fundraising,” said Smythe.

What are these traditional barriers? Smythe explained that conservation agencies generally rely on funding from once-off grants and donations, as well as fundraising events and ecotourism. Covid restrictions for the most part put paid to events and tourism as funding sources, although with the rollout of vaccines this was expected to change.

Grants and donations are another matter. Conservation agencies typically fish for these in the same traditional streams, jostling for limited funds. Well-known conservation agencies, with their bigger brands and reputations, long-standing audiences and extensive systems, land the big ones. Smaller agencies struggle for what’s left and often lack the technical resources required to effectively raise funds in a digital age. This is a pity because many small agencies do critical work conserving wildlife.

Smythe reckons that cutting-edge technology enables efficient, swift and transparent conservation fundraising without the bureaucracy, inefficiency, politics and corruption that sometimes plague large, traditional organisations. It also makes it easier for donors to split their giving, supporting many smaller funds that underwrite conservation efforts at a regional or local level, instead of contributing to one, big, global fund. Globalisation and new technologies tend to favour large organisations; Wildcards helps smaller agencies get their foot in the funding door.

While traditional funding models tend to provide once-off, lump sums to agencies making it tricky for them to budget and plan ahead, the platform, by contrast, opens more consistent revenue streams for conservation agencies.

Donor fatigue is a factor too. Long-standing donors are bombarded with pleas for funding from a range of conservation agencies, all anxiously to keep their projects going despite the pandemic and an uncertain future. Donors feel unrewarded and detached. Wildcards allows for recognition and “gamifies giving”, making the process fun and easy.

Digital natives

The way it works can take a bit of effort to get your head around, but it’s intended to appeal to digital natives, cryptocurrency fans and traders: Guardians, as Wildcard holders are known, donate to the conservation agencies that help conserve the animals of the wildcards they own. Each time a card is bought by a new guardian, revenue is collected by the outgoing guardian, 5% or less of this revenue goes to running the Wildcards platform. A guardian can make a profit when he sells a wildcard if the price he gets exceeds what he paid for it plus the donations he made to a particular conservation agency while guardian.

The amount a guardian donates to maintain ownership of a wildcard is a proportion of the price he is willing to sell the wildcard for; the proportion differs between wildcards. When a guardian buys a wildcard he must set the price he is willing to sell it for, the higher the price, the higher his donations will be.

Sales of Wildcards virtual animal NTFs have raised more than 130,000 USD for its 29 wildlife conservation agency partners in North America, South America, Africa, and Asia.

At present, Wildcards can only be bought with cryptocurrencies. The Wildcards team is working to change this so it can accept government-issued currencies too, but they feel cryptocurrencies offer many benefits. Transparency is a big one. Wildcards let donors see that the money they are giving is going where it’s intended because cryptocurrencies make the flow of money traceable as the blockchains they use are open public ledgers.

Another benefit of cryptocurrencies is that crypto funds can be moved around the world without paying international transaction fees. There are still some fees involved in the process depending on where the conservation agency is or how they are converting the funds, but these are low and decreasing.

Energy guzzling

It all sounds tremendously positive, but are NFTs bad for the environment?

Other blockchain initiatives, most famously Bitcoin, the crypto-currency platform, have come in for criticism for the energy guzzling (and therefore CO2 spewing and climate change-fuelling) computer power they require. It is estimated that a single Bitcoin transaction produces roughly 707.6 kilowatt-hours of electrical energy–equivalent to the power consumed by an average U.S. household over 24 days.

Wildcards has never accepted energy-hungry Bitcoin. When it launched in 2019 it used the Mainnet Ethereum blockchain platform – related to Ether, the world’s second-largest cryptocurrency. Smythe said that at the time this was the best option for the platform but things are changing as the number of Ethereum users has grown and the price has risen.

This rising popularity has come at a price, both financial and environmental. “The more people using Ethereum the more the price of transactions goes up – so much so that it doesn’t make financial sense for a certain class of applications to use it. As this happens, Ethereum uses an increasing amount of electricity through the process by which transactions are secured – since there is more money to be made in this process,” Smythe said.

Higher transaction fees meant less of the money Wildcard holders were donating was getting to the conservation organisations on the ground. While the increasing electricity consumption meant it was adding more to carbon emissions. How much electricity a single NFT uses is not fixed and tricky to even guess at. Working out how much carbon a transaction adds is further complicated because a lot of energy used is renewable. Nevertheless, it was estimated that a single NFT, such as a Wildcard transaction on Mainnet Ethereum, added 90kg of CO2 to the environment, the equivalent of an hour of a passenger’s international commercial jet flight.

Switch

The Wildcards team felt this flew in the face of their mission of protecting nature and rewilding the world and last year switched to the Polygon network.

Smythe said Polygon makes transactions greener, cheaper, and faster. Polygon draws relatively little electricity because it uses “proof of stake” instead of “proof of work” to verify transactions on its blockchain. They differ in that the former relies on users “staking” cryptocurrency, with finance and economics securing the blockchain; the latter relies on other users solving complex mathematical problems to verify transactions, in effect electricity use secures the blockchain.

The switch to Polygon is good news for Wildcards’ partners as it reassures donors the money is reaching projects on the ground. “I love that I get to work with magic internet money from the future, new kinds of economic mechanisms and work on the bleeding edge of the biggest challenges of blockchain technology – all the while making tangible, real-world impacts to conserving wildlife,” said Smythe.

Proud

The Johannesburg-born geek spends holidays hiking and camping in nature, motivated by the country’s natural beauty and the diversity of its wildlife. He is particularly proud to be associated with the Wild Tomorrow Fund, Wildcards’ oldest partner. The fund is creating a wildlife corridor, linking two existing large-scale wildlife reserves: iSimangaliso Wetland Park and the MunYaWana Conservancy.

The corridor, called the Greater Ukuwela Nature Reserve, was recently declared a protected area and in the future plans to drop fences with the neighbouring reserves to restore the natural connection between the mountains and the ocean in northeastern South Africa. This will let black rhino, African wild dogs, elephants, lions, leopards, cheetah, hyena and other threatened species once again move across the landscape.

But making this happen takes money. The corridor will need to be rehabilitated and protected; Big Five-proof perimeter fencing must be erected; alien invasive plants removed; patrol infrastructure set up; and rangers and reserve management hired and paid. Wildcards have so far contributed over US $30,000 to the Wild Tomorrow Fund, much of which has gone to paying for the new wildlife corridors land.

Wild Tomorrow Fund’s co-founder and chief operating officer, Wendy Hapgood said that “directly thanks to Wildcards and their tech-savvy supporters, the equivalent of over 25 acres of land has been saved”.

Call of the wild

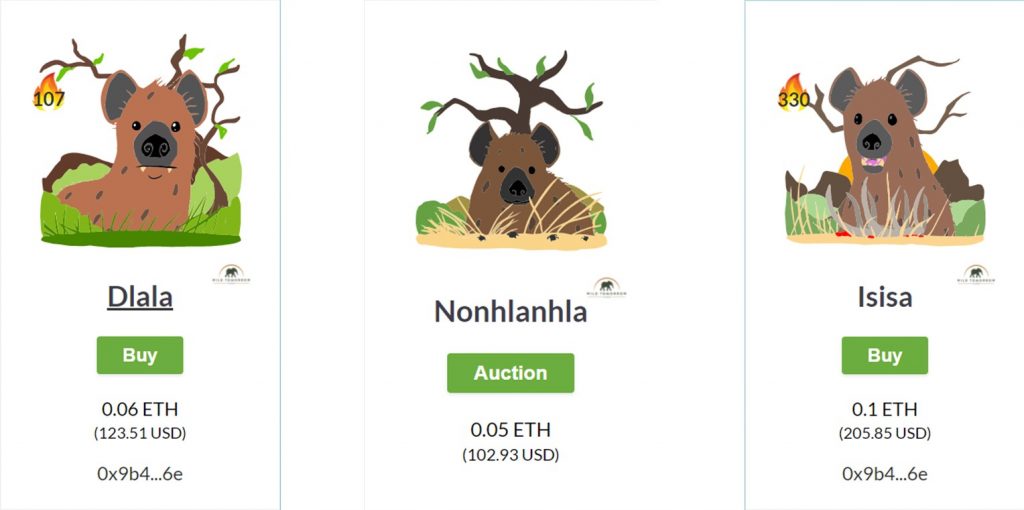

Smythe hoped contributions by guardians of the Dlala, Nonhlanhla and Isisa hyena wildcards will continue to generate funds to help the Wild Tomorrow Fund and save more land for wildlife.

He is “deeply troubled by the horrific occurrences of poaching, destruction of natural habitats and pollution” but is gratified that Wildcards was helping to educate people about conservation and fund projects to reduce threats to wildlife.

Recently, the Wildcards founders holidayed together in Kruger, drawing fresh inspiration from the national park’s rich wildlife, including many species that benefit from their platform and its guardians.

At camp after a day of game drives they would fall asleep to a chorus of hyena howls and the occasional lion’s roar. It reminded Smythe of that late night he had spent on watch at Hluhluwe-Imfolozi. Back then, peering into the dark and seeing a lioness, he was frozen stiff, in awe of the wilderness. Today the wonder remains, but the view has gotten a lot wider. – Roving Reporters

First published by Daily Maverick

- This story forms part of a Roving Reporters biodiversity reporting project, supported by the Earth Journalism Network. Rio Button is a marine biologist, commercial diver and surfer and regular correspondent for Roving Reporters. She has a Masters of Science degree in Conservation Biology from the University of Cape Town. She is also the chief conservation officer at Wildcards.