Conservation and efforts to tackle the illegal wildlife trade begin at home, says an Mpumalanga man, determined to practise what he preaches. Mieneke Muller reports

First published by Daily Maverick

As a herd boy, caring for his grandad’s cattle in Zanghoma, a village near Tzaneen, Vusi Tshabalala seldom gave hunger or thirst a second thought. He was too busy having fun in the veld. “It was only when we entered back into the gates of our yard that I would remember, ‘Actually I haven’t eaten today; I’m quite hungry’,” says Tshabalala.

Two decades on, Tshabalala is still sustained by a boundless flow of energy. He channels it into sharing with others a love of South Africa’s open spaces and an appreciation for its wildlife.

But he has deep concerns, rooted in his exposure to wildlife trafficking.

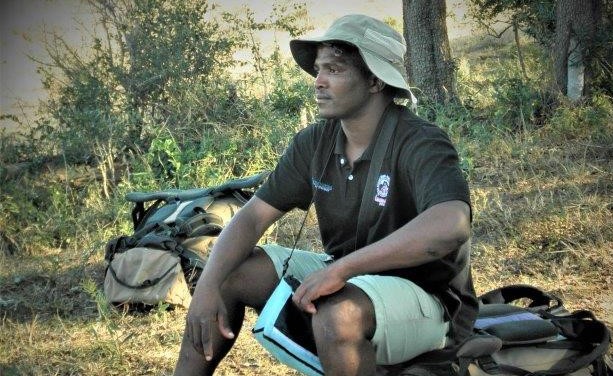

We meet Tshabalala at his stables in Acornhoek, a village just south of the Mpumalanga-Limpopo boundary and a few kilometres west of the Greater Kruger – the national park itself and the patchwork of private reserves bordering it.

He leaps up to greet me, a bounce in his step and wearing a vivacious smile. Tshabalala tells me he settled in Acornhoek because it’s near Kruger. He had also met a local woman, Splender, who he later married. The couple have two girls and one boy.

“I saved up enough money and with the help of my community leaders, I managed to secure 4 hectares on the edge of my community.”

Nature buff

The nature buff first got to know about animals herding his grandfather’s livestock, especially donkeys as a boy while visiting family in Zanghoma. “I grew up loving horses, and dreamed of owning some one day, the most beautiful animals ever,” he says, beaming. With a place of his own in Acornhoek, here was a chance. He started with two semi-wild mares, Queen and Nyeleti (Star), along with their yearlings, Prince and Moon.

But he knew others in Acornhoek might not see things the same way. Few of his neighbours had encountered horses in the flesh and many were afraid of the animals. How could anyone appreciate the natural world, he wondered, if they’ve never really interacted with it? And if that’s true for domestic animals, like horses, it applies to wildlife too.

The realisation proved to be one of those light-bulb moments.

“As a conservationist specialising in education for sustainable development, I have always struggled to find ways in which our young people can interact with wildlife – only a lucky few get the opportunity to go on a trip to Kruger National Park,” he says.

Here was an opportunity to change things for the better. Soon Tshabalala’s horses had become famous in Acornhoek and now on those endlessly hot Lowveld summer days, he takes local children for rides to swim in the nearby river.

Crisis

At 31, Tshabalala has spent much of his adult life working on environmental and conservation projects involving communities.

He sees his little farm very much as part of this work. It lies a few kilometers from the Orpen gate, just off the R40 which roughly skirts Greater Kruger’s western boundary. Across the road and on the other side of a closely monitored game fence, the park is battling to prevent poaching of endangered animals.

There have been large declines in certain species, particularly rhino. According to recent statistics, the rhino population in Kruger has decreased by 60% since 2013. Only 3,529 white rhinos and 268 black rhinos remain in the park. Other animals, notably pangolins, lappet-faced vultures and African wild dogs are under threat too – either poached directly or caught in snare intended for other animals.

How to tackle the scourge of poaching and the illegal wildlife trade remains a vexing question. Anti-poaching patrols and other security measures have enjoyed success but it’s an expensive undertaking and distracts park managers and sucks up financial and resources needed for other important conservation work.

Private reserves in the Greater Kruger spend huge amounts on security with no financial assistance from the government. According to Conservation Frontlines, the 2020-01 operating budget for the upmarket Timbavati Private Nature Reserve alone was just over R22 million, with security getting the biggest share (45% or R9,9 million).

Aside from millions spent on combating rhino poaching, trying to stop the bushmeat trade has proved costly too.

“Until recently, you would often see people around here walking about with wheelbarrows of meat to sell,” says Tshabalala. People were regularly poaching in neighbouring reserves – at least once a fortnight.

So the owners combined security, formed Farmed Watch and installed cameras along Orpen Road, says Tshabalala.

“Now when a person is sighted going into a reserve, each owner sends out a vehicle with rangers in it, so a guy ends up with as many as 17 vehicles looking for him,” says Tshabalala.

Then there is the conflict between wildlife and people, arguably the biggest threat to South Africa’s protected areas.

Amid all this, there is a feeling among some commentators that people living near parks like Kruger have been sidelined. Critics charge that many of the park’s nearest neighbours are deprived of access to its resources; are often the first to suffer when wildlife breaks out, threatening people or destroying crops; and point out that in some cases are descendants of people forcibly removed from the park over the course of more than a century.

Mending fences

Since he settled in Acornhoek in 2011, Tshabalala has been doing his bit, helping to mend fences, as it were. In a certain sense, it’s with his own good interests in mind. In the 13 years since he began his studies in nature conservation at Tshwane University of Technology, Tshabalala has developed a very hands-on love for animals, and biodiversity generally, one which he suspects raises eyebrows among his neighbours.

“I started preaching conservation and I had to come up with solutions to environmental challenges to make my community accept me. Participating in snake wrangling and crocodile breeding, I would have easily been mistaken for a witch, but coming through the lens of conservation first meant they understood me and how I’m passionate about animals,” he says.

The word “preaching” is apt here. Tshabalala’s father was a reverend in the Evangelical Presbyterian Church and he and his family moved often in the course of his work. Tshabalala Jnr, as a consequence, attended many schools and can now speak nine of South Africa’s official languages. Time spent in the Netherlands as an exchange student only added to his rapport with people from many different cultures and walks of life. It’s also part of the reason for his easy fluency in Afrikaans.

Eco-friendly church

He has followed in his father’s footsteps too. When not preaching conservation, Tshabalala Jnr is a pastor for Church of Love Ministries. But it’s not really one thing or the other. He says he brings all aspects of his beliefs into his projects and vice versa. So when he began work on a church building, he took pains to make it eco-friendly. Recycled glass and tin have been pressed into service and 2-litre plastic bottles used to make what are called eco-bricks.

At first, not everyone saw the light. “There were a lot of doubts about this building at first, people were saying, ‘It’s not going to work’, but slowly they came around, realising it works, it’s cheap and it uses waste. Now my congregants want to incorporate this style into their own homes.”

So how did the son of a preacher man, admittedly one who loved the bush as a boy, end up doing environmental work?

Tshabalala speaks with great affection for his childhood which included long stays at his grandparents’ home in the countryside, where he first nurtured his love for animals. “Having spent so much time with animals, I also created a big bond with them. I enjoyed that time so much I couldn’t wait for the school holidays to go visit,” he recalls.

Family phobia

It took a while, though, for this to translate into a career choice. “I never thought of going into conservation, until I saw animal abuse… Even when I began studying nature conservation, I knew I wanted to tend to human-wildlife conflict issues,” he says.

His family thought otherwise, though and did their best to dissuade him from studying conservation, but Tshabalala remained steadfast. “Everyone in my family has a phobia of animals. My mother even took me to psychologists to try to find other options, so to do conservation, I really had to go against the wishes of my family.”

His studies led to a series of jobs. To name a few, Tshabalala has worked as a zoo-keeper, in anti-poaching and game capture.

Community projects

“I came to this area (Acornhoek) in 2011. Every opportunity was linked to one another. Eventually I became a supervisor for a not-for-profit, Nourish, on a community-based project that educates local schools and communities about the environment and South Africa’s wildlife.”

It all proved great preparation for his current role as a manager of the environmental monitors programme at Kruger to Canyons Biosphere. The not-for-profit company works with communities to promote a balanced and sustainable relationship between socio-economic development, conserving biodiversity and the use of natural resources on which people’s livelihoods depend.

Poaching

Tshabalala now works on 86 different community projects, meaning he’s often in talks with local chiefs and their people, including discussing how poaching affects them. And he has come to understand the complicated feelings many communities have towards protected areas and conservation.

“There are two types of poachers that we usually see, depending on the community they come from. In some, they are considered heroes and whatever profits they make from poaching, they give back to their community and then there are those who act as individuals and simply get richer for their own sake.”

He says many communities protect poachers, knowing they provide for them in ways nobody else can or will. Some younger people look up to poachers. They understand jobs are scarce and poaching a single rhino horn could set them up financially.

And in some villages and settlements near Kruger, people have few interactions with the park and its animals, so can hardly be expected to appreciate it all, says Tshabalala. But by the same token, there has been a push back against poaching.

“There is a small settlement on the northern banks of the Olifants River called ‘The Oaks’ that had a lot of bush meat poachers, so the surrounding reserves wouldn’t hire anyone from that village, fearing that whoever they hired would give out information that would put their reserve at risk. Soon enough, the village understood they were missing out on employment opportunities, and how poaching was affecting their community.”

This led to discussions between Tshabalala and the people of The Oaks. Now many from the settlement work for canine anti-poaching units, putting their tracking skills to good use.

Radio

Such is Tshabalala’s energetic personality, wide set of skills and life experience, that he’s continually drawn into projects and undertakings. In his leisure time (if that can be the right word) he’s even turned to presenting community-nature programmes on a local radio station, RFM, and in 2019 represented South Africa at the 40th UNESCO youth forum. The forum brought together young leaders in conservation to join efforts and ideas to solve biodiversity issues globally.

“There’s a big diversity in the projects I’m working on. Some are community-enrichment, animal rehabilitation, environmental education, monitoring ecological issues and human-wildlife conflict within the biosphere of the Kruger, which is the most challenging project. It’s such a diverse and complex issue that’s not just for our landscape and our nation but it’s a global problem,” he says.

Towards the end of our conversation, I ask him what ordinary South Africans could do to aid conservation.

It begins at home and it calls for unified action, says Tshabalala. And it matters not whether that’s an eco-friendly smallholding near Greater Kruger or an urban flat.

“Before you want to join any organisation, any movement, it starts with how you recycle your own waste at your own home, how you preserve water. What’s making the world more sustainable and green is people coming together, be it in the form of an institution or organisation, because they see a gap and craft a solution to close that gap.” – Roving Reporters

- Mieneke Muller is a content writer enrolled on the Khetha Journalism Project. Supported by USAID, the joint WWF-SA, WESSA and Roving Reporters initiative assists aspiring journalists in reporting on the complexities of illegal wildlife trade in and around Greater Kruger.

This story, first published by Daily Maverick, is free to republish provided the article is used without any changes to the text. It must also include Roving Reporters story byline, picture credits, the footnote above and a link back to this post.

Now read… Old divides dog conservation efforts

BLAST FROM THE PAST: The bust of Paul Kruger, president of the Transvaal Republic, near the national park and a gate to it that bears his name. Nearly 120 years after Oom Paul left office and a few years short of a century after the park was proclaimed, conservationists are still struggling to win support from many people in communities bordering the park. Read on . . .