Vulture brain trade vexes conservationists

Unless the poisoning of vultures for alleged belief-use by bogus traditional healers is decisively tackled, these raptors – crucial to our ecosystems – face a very uncertain future. Dominic Naidoo and Alexandra Howard report.

Peter Jean Roberts remembers the grisly event all too well.

It was two days before Christmas, 2019. He had been enjoying family holiday time in a sweltering KwaZulu-Natal when a call came in. It was from a property manager on Rolling Valley Ranch, between Pongola and Mkuze in the far north of the province.

“We had responded to a previous incident in August that year on the same property, so when I saw his name come up on my phone, I immediately knew this wasn’t good,” recalled Roberts, who manages a wildlife emergency response team for the conservation organisation, Wildlife ACT.

Staring into his cup of coffee, Roberts relived the day. “Confirming my fears, the property manager told me he had found a poisoned African white-backed vulture, again. He asked for support. I contacted a couple of my colleagues and we converged on the site.”

“At first, we struggled to find immediate evidence of poisoning beyond this lone dead bird. The vulture had , however, clearly been poisoned,” said Roberts.

Aerial support

“The team needed aerial support to sweep the area to help find other birds or the laced carcass”, said Roberts, referring to how vultures are commonly harvested by lacing the carcass of a freshly killed animal with poisons and highly toxic pesticides.

After a 45-minute search from the air, the poison site was found.

“Waiting for us, in the open veld, was a snared, poison-laced impala carcass and 15 dead African white-backed vultures (Gyps africanus) and a lone lappet-faced vulture (Torgos tracheliotos),” Roberts said. Most were concealed beneath a bush near the impala carcass. The heads and feet had been cut off the birds, whose remains were still fresh.

Toxic meals

It was the fourth such incident recorded in northern Zululand that year, bringing the total recorded number of vultures harvested for body parts in the region alone to 53. The actual number of birds killed was believed to be much higher as many incidents go undetected.

As with nearly all vulture poisoning incidents, no arrests were ever made in the Rolling Valley Ranch incident.

Warnings

At the time, experts warned that unless the poisoning of vultures for belief-use trade was decisively tackled, vultures faced extinction not only in KwaZulu-Natal, but throughout Southern and Eastern Africa.

And it looks like things may have gotten worse. The Covid-19 lockdowns, coming after years of high unemployment and a stagnant economy, have pushed people to seek new sources of income. This includes poaching wildlife to be sold for belief-use, with some people convinced that animal-based concoctions could keep them safe from contracting Covid-19.

While the killing of vultures is not part of this recent trend, the writing has been on the wall for these raptors for some time. Some people believe they possess psychic power. This has led to false beliefs that muthi made from vulture brains could, for example, help you win the lottery.

False beliefs

According to a study in a peer-reviewed paper by ecologist Mbali Mashele, vultures play a significant role in the spiritual practices and occult beliefs of various communities in Africa. Mbali and her team interviewed 51 traditional healers and 197 other people in nine villages in the Bushbuckridge Local Municipality, near protected areas including Greater Kruger. They found that vulture body parts were commonly used by people hoping to see into the future, appease their ancestors, for good luck and to cure illnesses.

And a September 2020 scholarly paper highlighted that vulture poisoning was rife in the Great Limpopo Transfrontier Conservation Area, a vast area spanning national parks (notably the Kruger) and private and communally-owned land in South Africa, Mozambique and Zimbabwe.

The paper, published in the journal of Global Ecology and Conservation, noted a spike in intentional vulture poisoning and poaching. “Conservation stakeholders have identified evidence that a number of vulture species in particular ecosystems are being systematically targeted by poisoning with potentially significant effects on human, wildlife and ecosystem health,” said Meredith Gore, an associate professor at the University of Maryland, and her co-authors.

Worrying

A couple of years earlier, in 2018, conservation group BirdLife South Africa warned of widespread threats to raptors. In its “State of South Africa’s Birds” report, it listed 22 raptor species of the 80 known in the country, as either Threatened or Critically Endangered. These include the bearded vulture, Cape vulture, hooded vulture, African white-backed vulture and the white-headed vulture.

BirdLife South Africa noted a worrying decline in scavenger raptors and vultures, not only in South Africa but in Central, West and East Africa too.

Andre Botha, the Vultures for Africa programme manager at the Endangered Wildlife Trust said an ongoing aerial survey in the Kruger National Park had revealed a considerable decline in active nests of the lappet-faced vulture in the park since 2015.

Botha said the significant decline in numbers of lappet-faced vultures in two areas surveyed in 2020 was particularly concerning.

Then, late last year, Wildlife ACT reported that the lappet-faced vulture was well on its way to disappearing from KwaZulu-Natal skies. The not-for-profit said that an aerial and ground survey it did in November with the provincial conservation authority, Ezemvelo KZN Wildlife, noted an alarming decrease in active nests – from 15 in 2020 to four in 2021.

Parent birds

Wildlife ACT and Ezemvelo detailed how a Zululand Vulture Project team followed up on the poisoning of a lappet-faced vulture in the region’ north, visiting the nearest known active nest. “Sadly, a young vulture was found dead in the nest, suspected to have died from starvation due to the possible death of the parent birds,” the organisations said in a statement.

The nest belonged to a vulture that had been ringed and tagged as a chick in 2016 and fitted with a global positioning system (GPS) tracking unit in May 2020. Vultures only start breeding from the age of five so this may have been its first breeding attempt. “This individual’s GPS unit dropped off the grid in early October and the bird has not been seen again,” said Chris Kelly, a founding member of Wildlife ACT and its director of species conservation. “It is possible that the single remaining parent was attempting to rear the chick until it too succumbed to a poisoning event.”

Chicks on satellite

Four lappet chicks from other nests in Zululand have since been fitted with tracking units. The lightweight, solar-powered units let researchers monitor the birds’ movements when they are ready to leave the nest, providing a better understanding of the birds’ dispersal range, habitat use, flight paths and the threats they face. The units also help teams to respond quicker if abnormal movements are detected.

Intrinsic value

The lappet-faced vulture – named for the folds of flesh on its bald, pink head – is found in many parts of Africa as well as the Arabian peninsula. In 2015, the International Union for Conservation of Nature updated its status to Endangered. The African white-backed vulture, is also listed as once the most common and widespread vulture in sub-Saharan Africa, is listed as Critically Endangered, due to a decline of more than 90% in its population across the range over the past 35 years.

Why does this matter? Beyond the intrinsic value of the birds, vultures play a vital role in our ecosystems by consuming rotting carcasses. This limits the spread of certain diseases and keeps populations of opportunistic scavengers such as feral dogs in check, said Botha.

He said aside from deliberate poisoning and poaching for myth-based uses, vultures faced threats from a number of other quarters. This includes indirect poisoning – where vultures consume poison intended for predators such as leopards and jackals – and collisions resulting in electrocutions on electrical generation and transmission structures.

Mystified

So how have efforts to protect these important birds fared in the past few years?

Kelly said there had always been a strong presence of vulture conservation in KwaZulu-Natal, but poisoning for the illegal trade in body parts had been an increasing problem. Conservationists were mystified by the recent “spike” in vulture poisonings and were working to better understand its causes.

“There is also a sense that better monitoring and detection is part of the reason for the increase in reported incidents,” said Kelly. “Over the last three years, we have recorded and responded to over 14 vulture poisoning events, most of these in the greater Zululand area. More than 200 vultures died in those incidents, but many more were saved due to early detection and site decontamination. A few were saved and released back into the wild.”

Few arrests

What about catching and punishing vulture poachers? Why are there so few arrests and convictions?

KwaZulu-Natal SAPS spokesperson Lieutenant Colonel Nqobile Gwala said among the difficulties police faced was the fact that poachers were embedded in the communities, so people were often reluctant to share information with police.

“Potential witnesses are afraid to come forward with information or to testify as they fear for their lives,” she said.

While rhino poaching cases are referred to the police Organised Crime Unit, vulture poisonings are most commonly investigated by police Stock Theft Units which already have their hands full dealing with a deluge of cattle theft cases. They are sometimes assisted by the SAPS Endangered Species Unit, provincial conservation authorities bodies and SANParks, depending on where the incident took place.

On the investigation procedures, Roberts said an investigating officer would usually visit a crime scene with a forensic officer. They take photographs, bag samples for the lab for analysis and get statements from first responders and witnesses. All of this was used to open and build a case.

But how often were police able to build sufficiently strong cases that led to successful prosecutions?

Conviction rate

The KZN Stock Theft Unit confirmed it had handled six vulture poisoning cases in the past three years: one in 2020 in which four vultures carcasses found, two in 2021 (21 vulture carcasses) and three poisoning incidents so far this year (total of 97 carcasses found). Investigations resulted in the arrest of four suspects in 2021, but only one conviction with an accused fined R2000.

Before this, the only successful prosecution in Zululand was of two perpetrators back in 2011, said Botha. And given that many cases go by undetected, the actual number of vulture poisoning incidents and total number of vultures killed is believed to be far higher, he said.

At the time of going to press, the National Prosecuting Authority had not responded to queries on the number and outcome of vulture poisoning cases it has handled.

Reporting on the realities of the trade is complex and difficult. Disclosing the bizarre myths and legends that fuel demand may have unintended consequences, potentially increasing the demand for vulture brains, eyes and feet. Similarly, conservationists often caution journalists against reporting on the prices fetched for vulture and other wild animal body parts, lest it leads to more poaching.

Myths

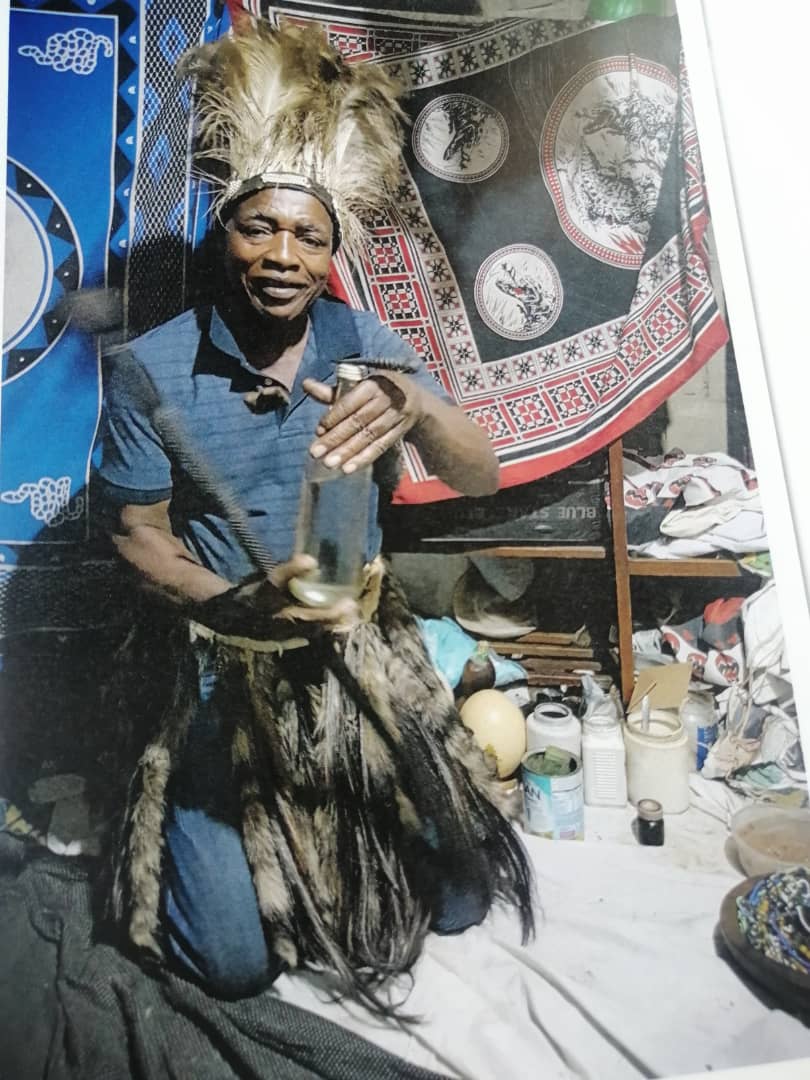

And the use of the popular term, muthi, for animal based concoctions is contentious. Muthi refers to herbal medicine prescribed by an inyanga (traditional healer), so belief-use is the preferred language of the day when it comes to the trade in wild animal parts.

However you choose to phrase it though, the fact remains that in African lore vultures are credited with supernatural powers – and how best to address this has got conservationists vexed.

Amos Kafera, a registered traditional healer from Zimbabwe says that the vulture (Gora, in Shona language) is widely recognised for its powers of prophecy. But people who knew how to make these powerful medicines had long passed on, says Kafera. “These days people are killing vultures indiscriminately. We do not encourage it. The bird should not be killed,” he says.

A spokesperson and former chairman of the KwaZulu-Natal Traditional Healers Association, Sazi Mhlongo, agreed.

He dismissed myths that consuming, smoking or inhaling muthi derived from dried-out vulture brains could improve odds when gambling on the lottery, in placing sport bets, or preparing for exams. He also scoffed at claims that vultures’ eyes can be used to see into the future or simply to improve eyesight; their beaks for protection and their feet to heal fractured bones or make a person run faster.

Bogus

“These false beliefs about the medicinal use of vultures are caused and perpetuated by people who do not have enough information about traditional medicine,” said Mhlongo.

”And traditional healers who are not trained practitioners and who want quick cash continue to mislead people by convincing them that killing a vulture or using the bird’s parts will create wealth for them,” adds Mhlongo. “They are bogus inyangas. These are senseless killings of a bird with no medicinal significance or healing properties.”

Livelihoods

He stressed that until people who live near protected areas were better off or were provided with other opportunities to make a living, it would be hard to stem the illegal wildlife trade.

And for as long as myths about vultures’ supernatural powers were believed, they would be harvested for their body parts, said Mhlongo.

He said that formal recognition of traditional leaders could help save vulture populations.

“We are the people who can help demystify these myths in communities,” said Mhlongo.

So, are conservation leaders, traditional healers and the users of wildlife muthi concoctions talking to each other?

Not enough, said Botha.

Engagements

“In my experience, engagements with traditional healer organisations are usually constructive in sharing information about the risks to human health from the consumption of poisoned vulture and other animal products, but more of this is needed on a continuous basis,” he said.

Encouragingly, when Mashele and her team did their research in the Bushbuckridge area, the traditional leaders they interviewed expressed concern about the fate of vultures and how this decline would affect their cultural and traditional heritage.

“Contrary to what was previously thought, vultures are indeed used in traditional medicine close to the Kruger National Park,” wrote Mashele. She expressed concern about the health risks people faced from consuming concoctions made from poisoned wildlife.

“We therefore encourage investigation into the human healthcare component, and sharing of results to create awareness,” said Mashele.

Diseases

Given the vital role vultures play, cleaning up carcasses and other organic waste, the Department of Forestry, Fisheries and Environmental Affairs warned that the decline in vulture populations could contribute to the spread of diseases among wild and domestic animals as well as people.

The department’s chief director of communications, Albi Modise, also expressed concern about the environmental impact of the poison-laced animal carcasses used to kill vultures.

He said a National Vulture Task Force was established in 2019, leading to the development of a biodiversity management plan for vultures, and a national wildlife poisoning prevention working group.

The working group, he said, had been making interventions to ensure wildlife populations were safeguarded from poisonous substances “through the safe and responsible import, sale, storage, use and disposal of agricultural pesticides and appropriate interventions to prevent and respond to illegal use.”

On alert

In the meantime, Roberts and his colleagues are on perpetual alert, awaiting summons to scenes similar to those they witnessed at Rolling Valley Ranch on December 23, 2019. “It’s not a case of will we get such a call, but when, and from where?” mused Roberts.

By the time the sun had set on that sweltering day, Roberts and the Wildlife ACT team had gathered all that remained of those 16 vultures into a single, lifeless heap.

“But there was more to be done,” he recalled. The poison that killed the vultures had to be removed from the natural system to protect other birds and wildlife. “We set the remains alight and watched the carcasses of these critically endangered birds disintegrate into ash.” – Additional reporting, Nomfundo Xolo, Tulani Ngwenya and Fred Kockott.

- Dominic Naidoo is a freelance environmental journalist. Alexandra Howard is a zoologist committed to finding people-oriented solutions to wildlife trafficking.

This collaborative story, first published by Daily Maverick, arises from the Khetha Journalism Project. Supported by USAID and developed by WWF-SA WESSA and Roving Reporters, the project explores the broader context of wildlife trafficking and examines ways to counter its impact, particularly in and around the Greater Kruger National Park.

Now read: BLAZING SADDLES: On the trail with community conservation champion, Vusi Tshabalala.