If you don’t want to lose the plot in writing a stunning narrative feature, read this!

Most writers – even the most accomplished – struggle with an outline of sort before they begin writing.

And as writers, we’ve also all been here . . .

You have this great idea, writes Jon Franklin, a Pulitzer Prize-winning science writer. Your enthusiasm is without bounds: the idea is so good you’re certain it’ll work. So you sit down, start banging away . . . In the beginning, words pour out smoothly and they’re nothing short of wonderful. A hundred words accumulate. Two hundred. And then . . . you start running into problems.

Something you did in the first two hundred words doesn’t quite mesh perfectly with something you had to do in the next one hundred words, but you’re not quite sure why. It seems to be telling you something . . . but what? You try to understand but, as you do, a certain confusion arises in your mind; that’s disconcerting and dangerous. So you back off. Ah well. You’ll fix it later. You push on.

You pound away some more, slower now. It’s becoming apparent that you’ll have to rewrite. This is not going to work totally on inspiration but, all the same, it’s still a really good story. You pound some more, slower yet. Something’s getting complicated. And then you hit another glitch, another inconsistency, and then another.

You press on, but . . . it’s getting harder, now; the copy is taking on the consistency of horse-hoof glue; and your mind is slowing down. You thought you knew where you where you were going, but your words seem to be carrying you somewhere . . . slightly different. Confusion oozes across your brain pan. But you know what you’re doing . . . that is to say, you did know what you were doing, but now you’re having trouble keeping it clear in your mind.

You keep forgetting to put things in; you need to go back while it’s fresh in your mind, but if you do that you’ll lose your place . . . and you can’t remember why it was that your main character had . . . oh yeah, that was because . . . but why . . .

And then it happens, you load one more thing into your active memory and it displaces something else. The whole structure of the story, which seemed so clear in the beginning, cracks and falls into pieces. You sit there looking at your writing, trying to remember who you are, what you were doing . . .

What happened? I have a word for it that’s actually printable. I call it “spaghetting.” – Jon Franklin

Franklin, the author of Writing for Story, is describing problems inevitably encountered when writing a narrative feature without a clear outline: a scheme that you use to sort out your thoughts and analyse your story before you sit down to write.

Simple story outlines

Franklin developed this simple, story outline method.

Complication: ______________________

– Development 1: _____________

– Development 2: _____________

– Development 3: _____________

Resolution: _______________________

This outline works well for dramatic narratives where a character confronts a problem (complication/challenge). We then follow the character though a series of actions (developments) that occur when the character confronts the situation through to a climax (resolution). In using this technique, Franklin insisted that outline comprise only five, simple three word statements, such as

Complication: Company fires Joe

– Development 1: Depression paralyses Joe

– Development 2: Joe regains confidence

– Development 3: Joe sues company

Resolution: Joe regains job

If you have en eye for story, you will notice that this structure contains the possibility of developing a classic narrative arc: setup, rising tension, climax, falling tension and resolution.

Also note that each statement revolves around an active verb. Active verbs are dynamic and essential for stories, and it is action, after all, that drives a good story. Click here to read more about active and passive voice.

In writing Mrs Kelly’s monster which won the first Pulitzer winner for feature writing, Franklin used the following outline:

Complication: Ducker gambles life

– Development 1: Ducker enters brain

– Development 2: Ducker clips aneurysm

– Development 3: Monster ambushes Ducker

Resolution: Ducker accepts defeat

>> Read more about Mrs Kelly’s Monster

If you are writing a story that sees a central character confront a problem and resolve it (or be defeated by it), give Franklin’s method a try. It works!

And if you want to follow the footsteps of Franklin in writing award-winning narratives order Writing for Story from Penguin Random House.

Explanatory narratives

Obviously not all narrative journalism stories lend themselves to the classic story arc with a complication and resolution, but are often more about issues – poverty, education, conservation, biodiversity, rhino poaching, the climate crisis, you name it. They should all, though, have a central sympathetic character – or several key people – at the centre of the action. In other words, use people and their experiences to illuminate issues, and drive the story. It is essential you do not ignore this.

In covering a topical issue, an unfolding event, a research project or some latest breakthrough in science, explanatory narratives are often the way to go.

In Storycraft, Jack Hart provides several simple story outlines for explanatory narratives which are common in science writing.

Two structural elements make up an explanatory narrative, says Hart:

- Action line

- Digression (explanation)

Overall shape

The action line creates the stories overall shape, moving the narrative through time and space. It draws readers into the narrative by exploring new places, introducing new people, and creating mild dramatic tension, if only because the person does not know what will happen next.

Digressions provide the actual explanation, placing all the action – what the people are doing, or an unfolding event – in some larger context.

“The clever toggling of action and explanation makes a well-crafted explanatory narrative enormously compelling,” writes Hart. “Sketching out the structure, which is something I do with every narrative I edit, produces something that looks like this”:

Outline for an Explanatory Narrative

Opening narrative scene

Digression 1

Narrative scene 2

Digression 2

Narrative scene 3

Digression 3

Narrative scene 4

Digression 4

Narrative scene 5

Digression 5

Hart describes this overall story shape simply: a layered cake.

In this overall shape, the narrative scenes contain all the action; the digressions provide the explanations, placing the action in context – where the action is taking place, why, how and when etc.

Depending on how long each narrative scene and digression is, one could easily end with a very tall cake of more than 2500 words – even a lot more – if one used the above outline. And you would probably also well end up “spaghetting” if you have not found the story line that holds all the layers together! So if one is considering writing a standard feature story of 750 to 1500 words, Hart recommends what he refers to as a 3 + 2 explainer – a structure containing three narrative scenes separated by two digressions. In outline, it looks like this:

The 3+2 Explainer

Narrative 1: Introduce the lead character/s and pose the explanatory question

Digression 1: Provide the necessary background and overall context

Narrative 2: Follow the lead character/s though the main body of the action line

Digression 2: Complete the explanation

Narrative 3: Bring the action line to a logical stopping place

The core purpose of an explanatory narrative — duh! — is explanation. The action line exists because it is an effective way to how something works. Some story elements inevitably appear when you describe action. The characters you introduce along the way face problems they most resolve. And scenes, one of the key ingredients in any more complete story, also play a critical role in explanatory narrative. – Jack Hart.

Jack Hart’s Story Craft: The complete guide to writing narrative non-fiction is available from Amazon.

Now read: Rollercoaster: How to take your readers along for a ride

TAIL PIECE ADVICE

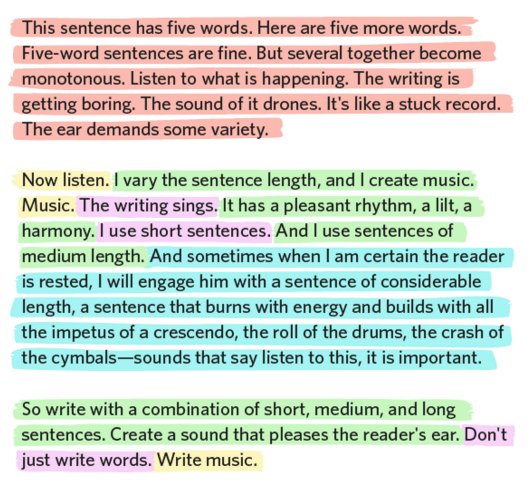

In closing, we share these lines from Gary Provost, demonstrating what happens when a writer experiments with sentences of different lengths, as quoted in Writing Tools: 50 Essential Strategies for Every Writer by Roy Peter Clark.

Read more quotes from Gary Provost

Gary Provost (November 14, 1944 – May, 1995) was an American writer and writing instructor, author of works including Make every word count: a guide to writing that works for fiction and nonfiction (1980) and 100 Ways to Improve Your Writing: Proven Professional Techniques for Writing with Style and Power (1985).